The first brand new chapter for this volume (no prior version of this chapter existed for Aspie Mouse’s forebear), Ch. B explains Aspie Mouse’s origins: we meet his mother and four siblings; he leaves home — though not on his own terms; finds the mouse version of MIT (university), where he gets his current name, impresses everyone with his abilities, and graduates with a “Mouster’s” degree — ready to find his place in the world, armed with new maturity and tools (literal & figurative).

Starting at 10 pages in 2019, Chapter B expanded to 12 in 2020, and then to 26 pages in 2021. During that last expansion, some material was added to the early section of Aspie Mouse’s interactions with his mom and siblings; but primarily, more substance was added for each of his daily class periods — plus lunch — at the Mouse “MIT.”

In early 2022, Chapter Pre-A (Preface) was refocused onto 27 common characteristics of Autism, showing how they fit the behaviors of Aspie Mouse and other Autistic characters in this graphic novel. The emphasis is on the positive sides of these traits. In response, the remaining “action” chapters A-E in what’s now Volume I are being tweaked one last time, usually without adding pages to any chapter, in preparation of Volume I’s formal publication. Existing dialogue is modified — and new “thought balloons” are added — to better show the Autistic characters’ (mostly) thought processes and feelings these characters have — especially when they differ from, or add to, what they say out loud. This should help the reader better understand the motivations of these characters, and how (if) they’re trying to improve their interactions with the non-Autistic world. As Volume I is put into publication, these added features will then be put into Ch’s. F-I in Volume II, while new Chapter J will include these features as it is written.

Chapter B has completed these “tweaks,” except the copyright notice at the bottom of each page will be updated to read (c) 2019, 2024.

Notes for Chapter B, “Leaving the Nest for ‘M.I.T.‘”

Synopsis: The first brand new chapter written for this volume, Ch. B explains Aspie Mouse’s origins: we meet his mother and four siblings; he leaves home — though not on his own terms — finds the mouse version of MIT (university), where he gets his current name, gets the best of two cats, meets a female counterpart (who normally dislikes male mice but ends up respecting Aspie Mouse), takes classes — where we see him interact with classmates and instructors, impressing everyone with his abilities, and graduates tied for first in his class with a “Mouster’s” degree — ready to find his place in the world, armed with new maturity and tools (literal & figurative).

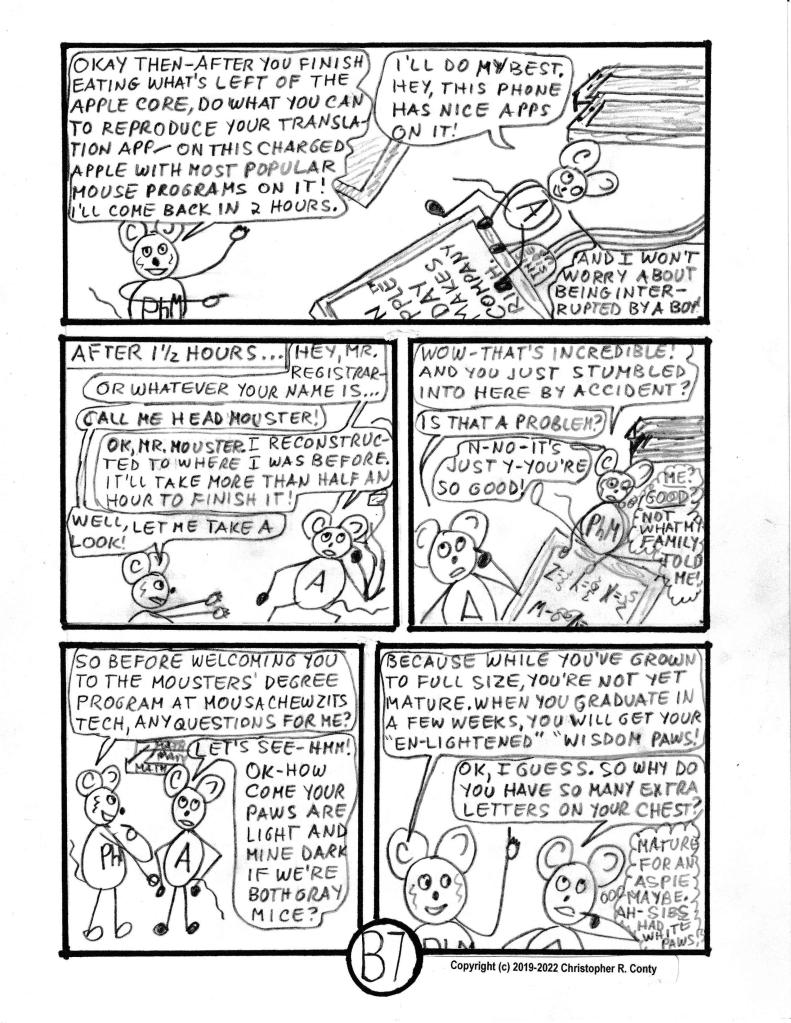

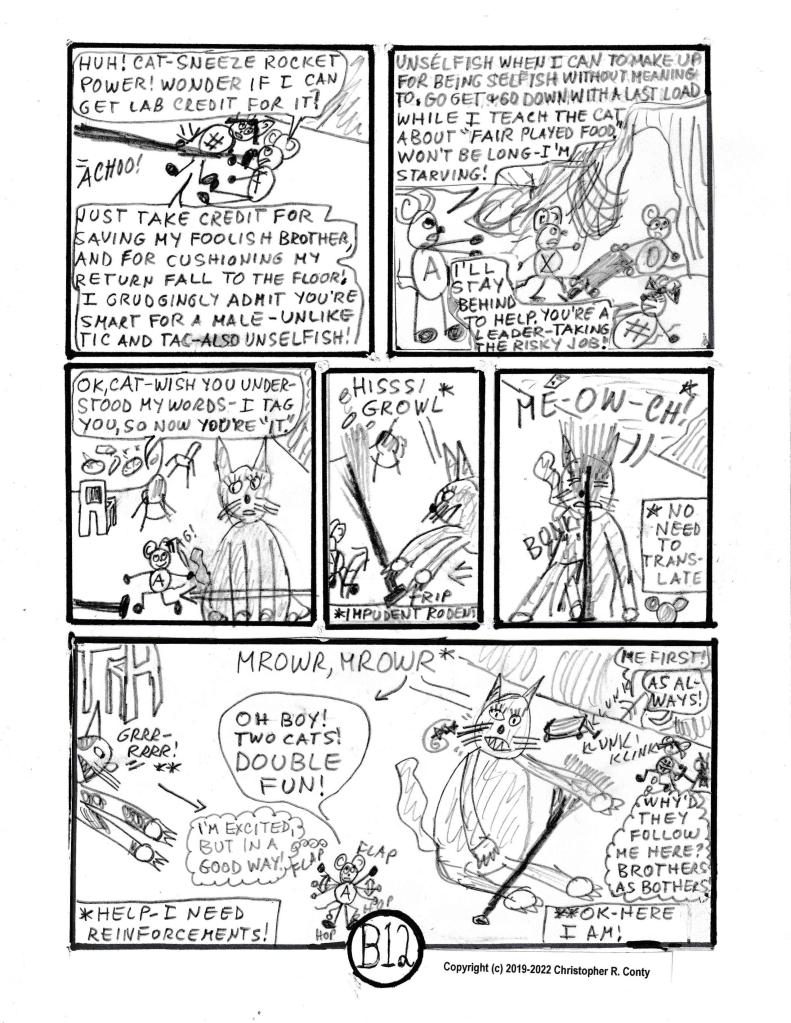

In terms of sequence of events in this graphic novel, Ch. B is really the FIRST chapter. It comes well before what’s shown in Ch. A (as explained in Ch. A’s notes). There was no precedent for this chapter in Aspie Mouse’s forebear decades ago: only one line in Ch. B (“Oh boy! Two cats! Double fun!”) is directly imported from one of those prior comic books. However, the context of that line — how two cats fail to capture him — plus the general tone of Aspie Mouse’s character, and how he interacts with other characters, are the same as they were decades ago — especially his “special interest” in loving playing with cats.

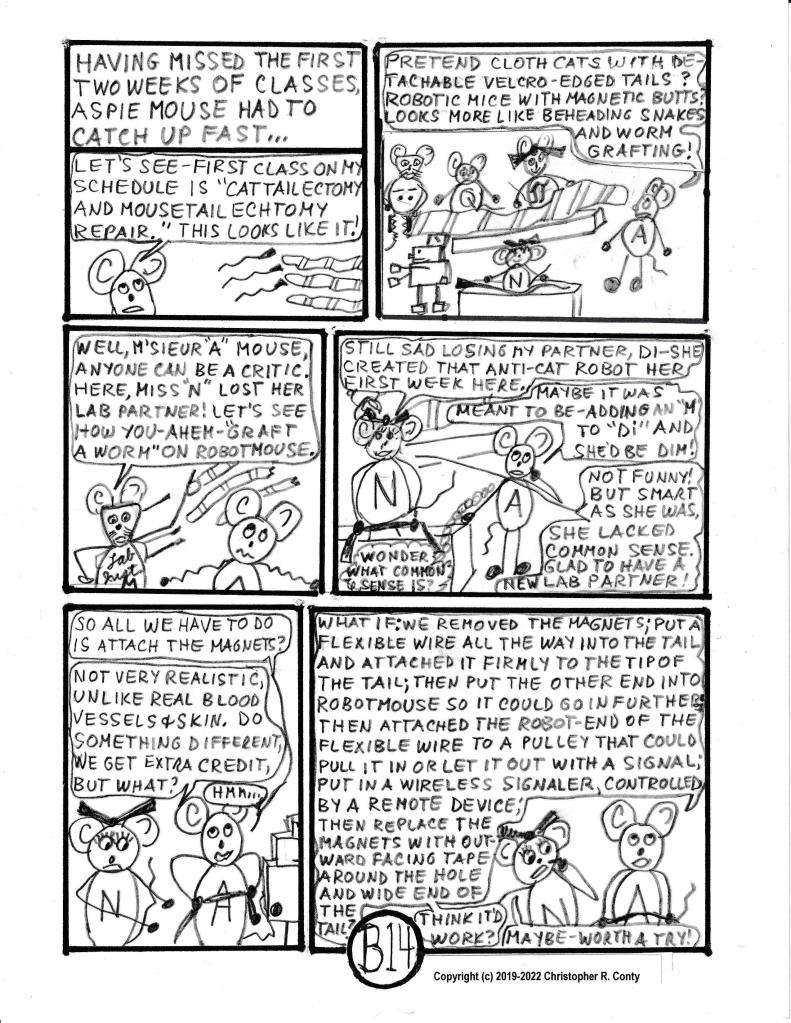

As Chapter B was written and then rewritten, certain topics got more fully developed, such as Aspie Mouse’s original living situation, family interactions — especially with siblings — and peer relationships — particularly at the Mouse “MIT.” Chapters A & C in Volume I, and G, H & J in Volume II also deal with issues around where to live (not just for him), while peer relations (with other mice/ rodents) get additional in-depth consideration in all five action chapters (F, G, H, I & J) in Volume II. The additions made in Ch. B make it better for identifying Autistic traits in Aspie Mouse and other Autistic characters; they also should improve in-class discussions and end-of-chapter questions on these traits.

Specific Characteristics of Autism Introduced or Elaborated On in this Chapter:

This chapter intentionally adds in several more of Aspie Mouse’s Autism traits vs. Ch. A, and continues the practice in Ch. A of identifying specific traits based on the list of 27 (arbitrary) Autistic characteristics carried throughout the graphic novel — though number identification of the traits in these notes goes down after this chapter. That should again make it easier to fill in the “chart” for Question B.1 (same exercise as A.1, using Ch. B’s characters). The 27 traits are listed in Ch. Pre-A page 8, then in each chapter at the beginning of the Question Set in this blog, and at the beginning of each Volume’s Notes/ Question sets in the back of the book — following all chapters’ panels — in the printed version.

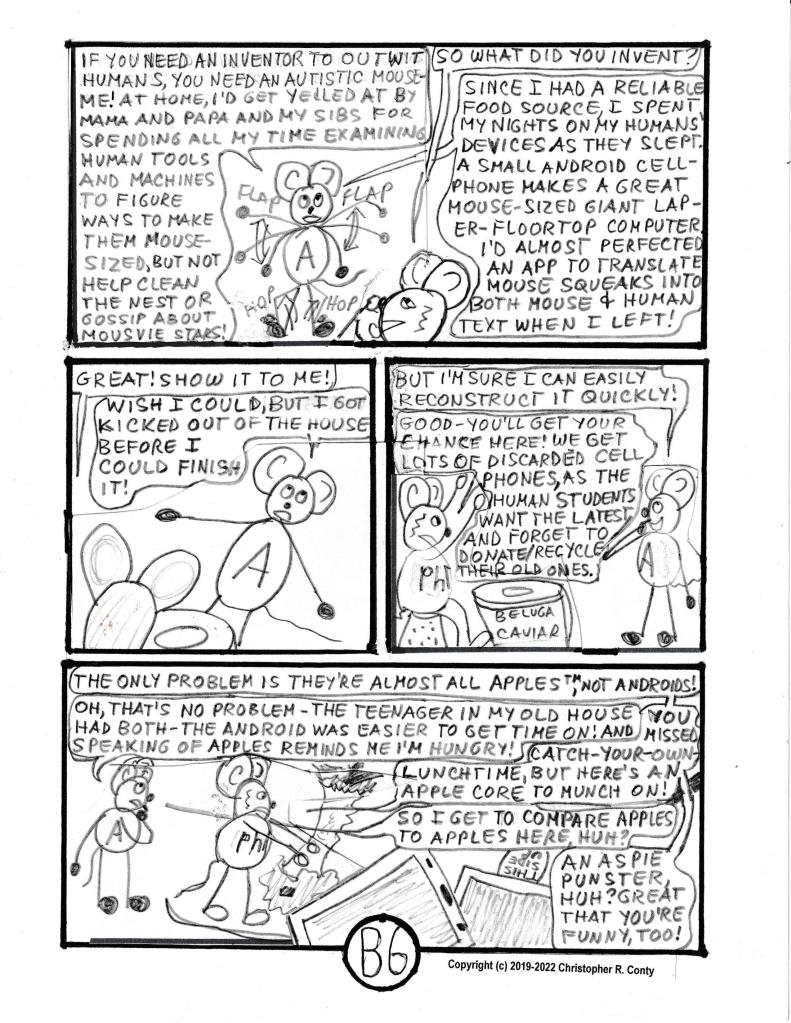

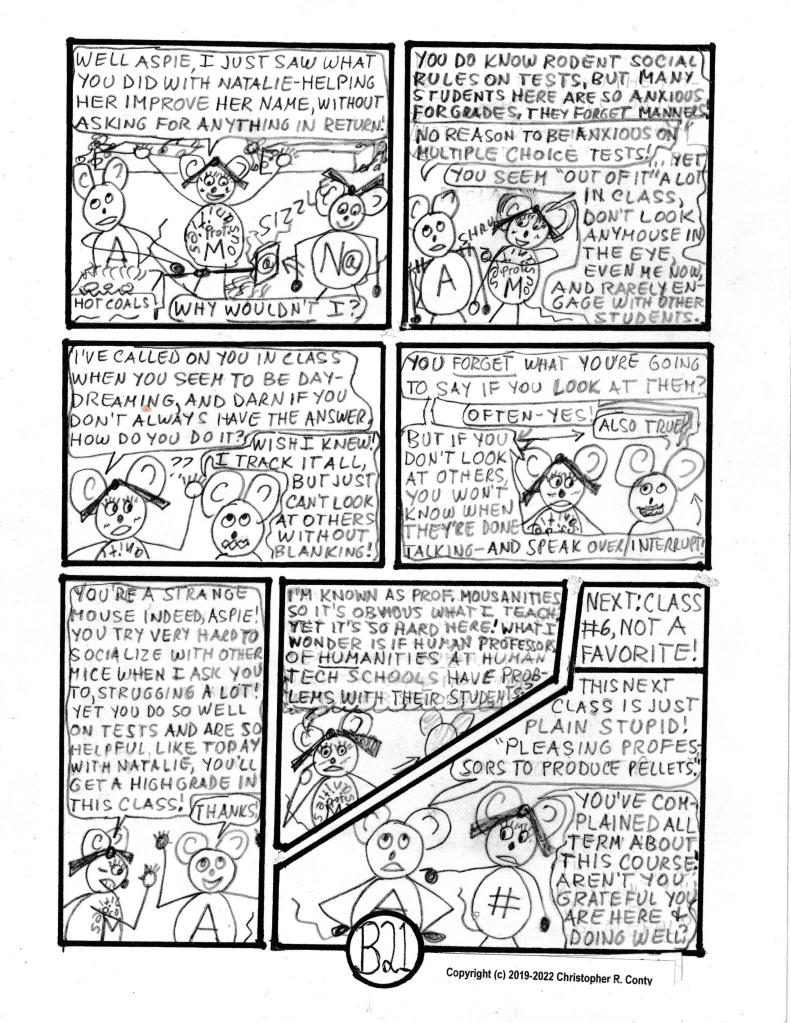

For example, on pages B-6, B-8 & B-24, we see AM “flapping” when excited (Trait #4, self-regulation/ stimming), a common Aspie behavior. Even though he’s at a school where many of the students (and faculty) have Autism, which means many of Aspie Mouse’s and others’ Autistic mannerisms are frequently overlooked or ignored — unlike in Chapter H, when these same behaviors will drive four Neurotypical mouse brothers crazy — Aspie Mouse still gets a lot of criticism/ pushback, especially from female mice (both Autistic and Neurotypical) for his lack of “social graces.”

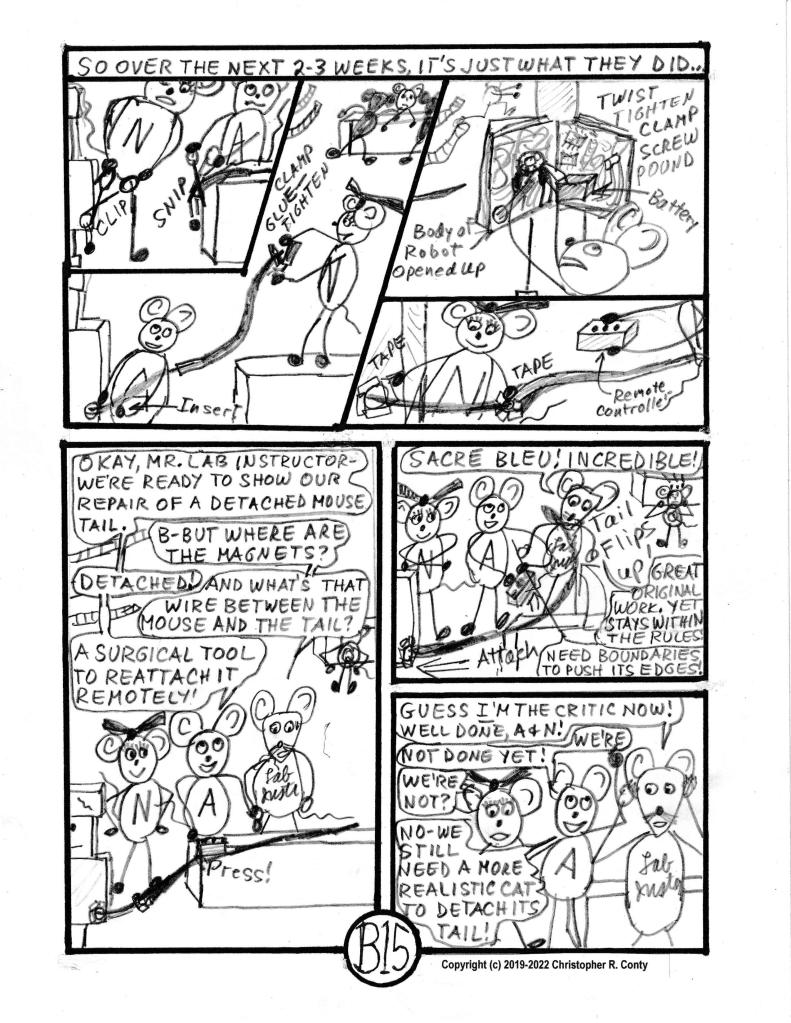

Among the “social skills deficits” Aspie Mouse exhibits or admits to having in this chapter (many of which fit into others of the 27 traits also, but especially #17, Unaware of impact of actions on others) include: poor table manners (pp. B-13 & B-19); being a picky eater (B-13, also in Ch’s. A & D); resistance to change, trait #16, with elements of #12, persistence and #14, rule-follower (refusing to go along with what he thinks is dumb, pp. B-14 & ff., but is rather rigid following his own rules); trouble remembering others’ names (pp. B-19 & B-22, trait #23); emotionally delayed — being emotionally “younger” than his peers (still wanting to drink from Momma after all his litter-mates are weaned, and having dark paws later than all but possibly one sibling, trait #19; disconnected from body — little concern for personal hygiene (doesn’t see the point of his 3rd period “Better Mousekeeping” course), trait #24; in terms of poor self-regulation (traits #2 & 3) and lacking social understanding (trait #8), not knowing what “common sense” is (page B-19), and a whole series of criticisms for speaking over, not looking at who’s speaking (no eye contact, trait #1), not seeming to pay attention, ignoring another’s space, etc., from “N/ Natalie, Toe/ Hashtag” and Miss Mousanities (pp. B-19 to B-23). As for the need for safety (trait #21, Lack of trust, all feels unsafe) — while resigning himself to the notion that safety doesn’t exist — look at Aspie Mouse’s thought balloon on page B-15 in which he says he… “need(s) boundaries to push its edges.” Those with ASD crave rules; and yet, many of those rules are pushed to their limits to test them: if they bend, but not break, the Autistic person is relieved (trait #14, rule follower)!

Another trait of Aspie Mouse first shown in this chapter is taking others’ words at face value: he misses irony, satire and hidden meanings in others’ words (one aspect of trait #15, Honesty, innocence, naivete). Page B-8 is the first use of what becomes a running gag throughout the rest of this work: Aspie Mouse confuses “literally” with talking about literature.

In summary, by watching Aspie Mouse interact with instructors and peers in each of his seven courses, plus a couple of his school day lunches, as noted above, there’s strong evidence of how clueless Aspie Mouse can be as to what his “expected” behavior should be in social situations; that is, he lacks social understanding (trait #8) and is unaware of the impact his behavior has on others (trait #17).

Low self-esteem: Before getting to the positive traits of Autism shown by Aspie Mouse in this chapter, here are a few paragraphs on what Tony Attwood (in “Been There, Done That…” previously referenced in Ch. Pre-A) says is the second most pervasive problem those with Autism wrestle with (second only to anxiety, per Ch. A’s notes): low self-esteem (trait #20)! Details on raising self-esteem in someone with Autism are beyond the scope of this work; whole books have been written on the subject. However, there’s one approach I (the author) especially like, having done it myself, though it took me years of men’s work to fully embrace it (thus I suspect it works better with adults than with pre-teens, adolescents or even young adults under age 25 — when the brain supposedly is finally fully formed in terms of moral judgments): avoid taking on other people’s “projections.“

Carl Jung (early 20th Century Viennese Psychologist, contemporary of Sigmund Freud), proposed the idea that we all have a “shadow“: the part of one’s self hidden from view, especially from oneself. My “shadow,” which lies within my “unconscious (mind),” reveals itself in my behaviors, especially when I engage in what Jung called “projection“: I get triggered by someone else’s behavior because it reminds me of a part of myself I’d rather not admit to having. It can be a positive trait: something I do well — such as kindness, generosity, solving complex math problems, etc. — but if while growing up, I was told “not to put on airs,” I may minimize these gifts, so I’ll praise someone else for showing them, instead of me.

More often (and problematic), is when I project a negative trait onto others. For example, I’ll blame someone else for causing my own out-of-control behavioral meltdown, even though my response to the “trigger” is in my control (in theory), not the other person’s (how could they control my response?): I could walk away, let it go, laugh it off, etc., even if internally I feel powerless to do so. It’s especially difficult for those with Autism and other related Social Pragmatic Differences to “let it go,” because we get picked on, teased, etc. more than others. As observed in Ch. A’s notes about anxiety, our executive function gets clogged up so easily (emotional dysregulation), greatly reducing our access to alternative resources we have when we’re not “triggered.” Yet even when I’m consciously blaming another for my meltdown — ignoring my “projection” — my unconscious self feels guilty and knows I’ve taken a hit to my self-esteem, because: (a) I don’t make any friends by blaming others; and (b) all the while I’m blaming you, my inner critic is beating myself up for not responding more calmly and for not coming up with a witty, withering putdown comeback.

Both positive and negative projections give me an unrealistic view of the world, because I’m putting a human being either up on a pedestal or into a hole where I look down on them. That’s why “It’s what you think, it’s not about me” is a useful internal response to anyone else’s projection onto me, a way to ground myself in reality and give myself a semi-permeable shield that allows me take in what’s useful feedback, yet ward off — reject — what isn’t, by repeating “it’s not about me” to myself over and over again. As is said in 12-step program rooms, “Others’ opinions of me are none of my business.”

What a lifetime of projecting one’s negative and positive traits onto others leads to is great difficulty treating others as peers or equals! I either put others down so I feel superior, or I put them on a pedestal and feel inferior. By “owning” my projections, and shielding myself from others’ projections, I’m more free to treat others on the same level — human, as I am, with both strengths and flaws. When don’t I need to use a “shield”? When what I’m sending, and what another person is sending, is pure love — expressing how I’m feeling in the moment (about me, and maybe, but not necessarily, about the other) directly from one human being to another: no agenda, and expressing no judgments (“be a witness, not a judge” as Jung put it — took me 20 years to “get it” and implementing it consistently is still a work in progress).

Anxiety, the Most Widely Experienced and Potentially Destructive Autistic Trait: Autism self-report anxiety as an issue — more than any other trait! Anxiety is not unique to the Autism community: I (the author) believe anxiety is so dominant in modern American society — and therefore exploited by advertisers, the clergy and politicians — that a book on “The Anxious Society and What to Do About It” is long overdue. What makes anxiety particularly damaging to those with Autism is two-fold:

(1) 98% of Adults with Autism self-report it as an issue in their lives, more than any other trait. The overall rate of self-reported anxiety in society overall is variously reported as 30%, 50% and 70%; even if 70%, it means fewer non-Autistic people are often anxious than those with ASD.

(2) When those with ASD are more anxious than usual, their more poorly developed pre-frontal cortex, responsible for executive function and self-regulation in the brain, gets “jammed” (like an older car’s faulty carburetor), the result is no access to resources and support available during calmer times.

In addition, those with Autism often say their anxiety lingers longer, it’s always present (true for this Author) — even if not crippling most of the time — and anxiety seems to spike more quickly, more often and more overwhelmingly than is observed for other personality types who get anxious (again, see Attwood, et al, Been There, Done That …*).

There are typically four responses to anxiety by anyone:

- Fight: Animated response: making extravagant gestures, speaking loudly, talking on and on, asking lots of questions; for some, it might literally mean punching someone or worse.

- Flight: Literally running away from the situation, going to another room in the house, or looking at one’s phone — walling off anyone else present.

- Freeze: The most common response by those with all forms of Autism. Deer in the headlights. My body stays present, but I seem unable to make any visible response.

- Fawning: Less well-known vs. 1st three. I try to “butter up” whoever triggered my anxiety by denying any emotional response: “No, I’m not angry; why would I be angry?”

As explained in Ch. Pre-A, Autistic people tend to be “all or none; black or white,” etc. That means those less often identified as Autistic, the extroverts, are more likely to respond with FIGHT when their anxiety spikes. I, the author, have gotten in trouble all my life, losing jobs, relationships, etc. from the consequences of acting impulsively (sending a damaging email, interrupting a meeting, yelling at inanimate objects not “obeying” me) as a result of suddenly elevated anxiety — and often I’m unaware it’s elevated! The negative result? Getting fired, losing relationships, not being trusted.

On the other hand, those most often identified as Autistic, the introverts, usually FREEZE and get very quiet when their anxiety spikes. They make few if any movements with their heads and face, don’t look at whoever is speaking to them, and don’t ask questions — even if they’re totally confused! Even I as an extrovert freeze more often than I fight. I’m especially likely to freeze whenever anger is being expressed, whether it’s about me or not, or if I’m being evaluated for leadership and things suddenly go weird. The negative result? I’m not present — as a parent, as a worker, as someone who should act differently in that social situation.

Either way — but for me, the Author, especially when I fight without regard of consequences — it leads to battening down the hatches, feeling very alone, and feeling very unsafe. Interestingly, low self-esteem (as noted, trait #20), which may even spur on generosity and humility in those with ASD (see positive traits below), is ranked #2 in how common or pervasive it is! When these traits combine together, they can lead to meltdowns (ranked #4). While meltdowns from anxiety are common in ASD children, they can persist through adolescence and well into adulthood. (For meltdowns, see Ch. C, including meltdowns vs. tantrums).

In a moment of high anxiety, all one’s energy is devoted to survival — leaving no space for awareness of others’ existence, much less putting oneself in another’s shoes or helping others in that moment. It’s what leads others to accuse those with Autism of being SELFISH. Aspie Mouse’s comment on page B-16, “Maybe I shouldn’t squeak thoughts out loud” reflects my experience of getting in trouble for speaking my mind, acting out as if I need to be the hero, or asking too many questions — all when I’m really anxious.

Most of the questions that follow these notes — certainly from Question Set B.4 on — relate to anxiety in one way or another, but specifically B.13.

Finally, most mental health physicians agree that Depression is a stronger form of Anxiety. Both conditions are treated with the same medications, meaning the body doesn’t distinguish between the two. Depression per se won’t be directly covered within these Adventures until Chapter I in Volume II.

*Source: “Been There, Done That…” by Tony Attwood; See references.

Now for the positive side of Autistic Traits shown in Chapter B:

We see how inventive Aspie Mouse is (Trait #11): he finds novel ways to solve problems that just don’t occur to others — often doing so in the moment in high pressure situations. What’s ironic is that many with Autism (including this author) function best in actual physical emergencies — where they’re LESS likely to panic, but instead shift immediately to problem-solving mode (Trait #9, Pattern-seeking/ solving problems in unique ways) — yet seem paralyzed and unable to make a decision when the issue isn’t a “life or death” crisis, but something requiring a decision, rather than solving a problem; or creating a “crisis” invented in one’s own mind — leading to anxiety (as discussed above), resulting in fight, freeze, etc. That’s one reason people with Autism — especially if they also have ADD or ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder/ Difference), as 3/4 of those with Autism do (again, source is “Been there …” by Attwood et al) — often make excellent EMT’s, first responders, Emergency Room Physicians and Nurses, Firefighters, Police, etc. If I keep moving, responding to crises, I don’t have time for my mind to play games with me that can be very upsetting, especially if shared. See Chapter C, where I discuss this again, with an example from my own life.

Aspie Mouse is a genius with computers (not true for me, the Author, who struggles with technology, but I’m so good with the English language that I’ll correct everyone else’s grammar and spelling, and wonder why they’re not thanking me!). Beyond computers, Aspie Mouse is good at finding physical solutions to every-day problems.

Another positive trait Aspie Mouse shares with a significant slice of those with Autism is generosity (not a specific one of 27 traits, but derives from #15, honesty, etc. & #7, difficulty identifying feelings). This subset of those with Autism (of which I am one, though more so as I get older; I judge so is Aspie Mouse) are often willing to give others the benefit of the doubt; they are often quick with genuine praise, while avoiding false “buttering up.” They may also, at the same time, come down hard on others, due to their projections.

One reason many with Autism end up being generous is that they identify with others with challenges who suffer from discrimination, etc. Aspies — like those with physical handicaps — are generally more accepting of ethnic and racial minorities, of alternate lifestyles, etc., partly because they don’t care what the “crowd” thinks, but also from sympathy or even empathy. When growing up — even in Junior High School — I (the author) generally avoided mentioning or making fun of other kids who stuttered, had visible physical deformities, etc. I knew this was right to do, even though my own “difference” showed up as over-sensitivity (Trait #22), leading to having frustration tantrums (poor emotional self-regulation!) as late as 9th Grade!

A related positive trait that Aspie Mouse has is what Neurotypicals would call humility. He doesn’t think of himself as a hero (and will continue to deny being a hero in the next three chapters), or as particularly clever, etc. See his reaction to Toe/ Hashtag’s compliments on page B-13 as they both slide down the pole after getting the banquet food. Partly, it’s an instinctive resistance by many with Autism to the idea of hierarchies: they’re often best off not being a boss. And if they have a boss, it’s best if that boss behaves more like a helpful parent, keeping them out of trouble so they can do their job excellently, versus a boss who plays “gotcha,” seeking an excuse to fire them due to their own discomfort. (This author was thankful when a colleague — awed & grateful for my product knowledge — asked me to stop eating while talking to customers in our trade show booth; great feedback, given my social norms awareness lapses. Neurotypicals hearing me tell this think this colleague’s behavior was totally out of line; I think it was essential feedback!).

Those who are generous to others help to contradict the popular impression that everyone with Autism is “selfish.” However, those acts of generosity and humility usually occur when the Autistic individual is feeling calm. The generosity — and even humility — can easily disappear when the one with ASD gets “triggered,” and anxiety (per above) suddenly is elevated. Note Aspie Mouse’s comment on page B-12: “… unselfish when I can to make up being selfish without meaning to.” And then on page B-19: “… generous when reminded!” These show his “low self-esteem” and strong “self-doubt.”

But generosity and humility also reflect the low self-esteem (trait #20) and strong self-doubt that come from years of hearing almost nothing but criticism. They’re developed more as self-preservation and deflection. They’re seen by the one with Autism (incorrectly?) as attempts to “make up for one’s deficits” — or even worse than deficits, perceived defectiveness — leading to hoping others will like them, respect them, be with them, because of their generosity/ humility. It’s like a bribe: an effort to hide their self-loathing by being generous and humble. Yet it’s a paradox: the others may still avoid them, not wanting to hang out with someone so negative about oneself, when it leaks out, as it inevitably does, given the lack of “filters”! Another not-so-positive motivation for being generous for those Autistic individuals who are extroverts is that it’s another opportunity to “be on center stage”: see how generous I am, which broadcasts being SELFISH — maybe justifiably

Downplaying both positive and negative behaviors commonly found in those with Autism can be a way of masking — the effort made to hide/ stuff down one’s Autism (not to disclose) in an attempt to “fit in” with Neurotypicals and avoid discrimination. Masking is not treated in this graphic novel as a “trait” of Autism per se, but in adults — and even children and adolescents — it’s an important defense mechanism to “appear to fit in.” It’s particularly pronounced in girls and women with Autism (such the author’s mother) to avoid social ostracism, which girls often fear more than boys. One way a female teen or pre-teen with Autism may try to “mask” is during or after a social situation with other girls: the Autistic girl is emotionally drained, exhausted. Meanwhile, the other girls are filling up their social needs tank and get energized. Masking works against the otherwise positive Autistic tendency toward honesty (a good trait), and when done consciously, may limit oversharing (limiting a less-welcome trait).

The final “topic” for general discussion in these notes is discrimination (prejudice), especially subtle forms of discrimination that may seem innocent, not all that harmful, until the consequences of millions of isolated actions of the same type are viewed all together. In this chapter, it’s about mice discriminating against other mice (also will be in Ch. H); in Ch. E, human discrimination gets some attention. Those with Autism diagnoses are discriminated against, especially in employment. Add a couple of other “targeted” groups that the Autistic individual may also be part of — such as being gay, non-gender-conforming, someone of color, and maybe having a speech impediment or a learning disability and it compounds. It’s disconcerting is that no discriminated-against group has as high an unemployment rate as those diagnosed with ASD: over 75%!

The first reference to prejudice/ discrimination in this graphic novel comes during a conversation between Aspie Mouse and Toe/ Hashtag that begins at the bottom of Page B-21, as they both attend the same 6th period class. After listening to Aspie Mouse grouse about the course they’re taking, and then wishing he were a white lab mouse so he’d be fed pellets regularly, Toe/ Hashtag tells him that he wouldn’t qualify as a lab mouse because of his color (gray, not white); but also, he really wouldn’t be happy doing that job, anyway. Toe/ Hashtag isn’t saying this to Aspie Mouse out of prejudice or to hurt him, but out of genuine concern for him. Still, her opinions could have the effect of limiting Aspie Mouse’s choices — if he listens to her from love or respect for her, instead of what his heart tells him he should do. It’s a limiting belief even though he’d likely reach the same conclusion as Hashtag about not liking being a lab mouse.

Yes, Toe/ Hashtag’s response has an obvious racial component he can’t do anything about (if true that only white mice are used in lab experiments). The more subtle message is about how individuals get “stereotyped” or “steered” into applying to certain schools, living in certain neighborhoods, participating in certain activities, and — perhaps most crucially — applying for certain jobs/ careers, all based on their perceived “comfort level” or “fit.” What Toe/ Hashtag is saying when she tries to discourage Aspie Mouse from wanting to be a lab mouse — with no ill intent — is what’s been said to millions of people throughout their lives to discourage them: “You wouldn’t be happy here”/ “You probably wouldn’t fit here,” or in the extreme, “Why don’t you go back where you came from?”

What’s true about those who make such statements is they are uncomfortable, and so, as noted earlier per Carl Jung, they cast a “shadow projection” onto these “others” to avoid facing their own personal discomfort! But the net result for society is that fewer folks take “risks” to push back on these prejudices. As one Black applicant for a sales position told me when I asked if he’d be OK being the first Black employee at that publisher, “I don’t want to be a pioneer!” They may avoid nicer, more convenient neighborhoods. (Racial covenants — “you may not sell or rent to Negroes/ Jews…,” enforceable by the courts — weren’t outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court until 1948!)

Victims of prejudice may be discouraged from exploring careers that may fit them much better — where they’d be happier and even make more money — because they lack: the money to attend college; and/ or role models who share their identity; and/or the ability to get to or past the Human Relations job interview to even speak to the hiring manager. They’re marginalized/ ghettoized into dead-end jobs and bad living situations. Therefore, certain schools, neighborhoods and professions end up predominantly male, (or female, paying less) or white, or black (again paying less), or heterosexual, or LGBTQ (into the arts), or Jewish/ Christian/ Muslim, or dominated by rich people (CEO’s), or poor people (making minimum wage) or full of workers in their 20’s and 30’s, because non-managers are nudged out by age 40, 45 or 50. In the context of race, it has been called “systemic racism,” a “trigger” word that’s received a lot of pushback by conservative groups. As I understand it, all it means is that prior prejudice (including slavery) is made worse when intentional government policies — such as Jim Crow laws, racial covenants (per above), and such benefits as home loans for veterans, company-paid health insurance, and the Federal minimum wage law were all “rigged” to make it harder for Blacks to qualify. At worst, it’s worth discussing, not burying. Frankly, I’m open to being proven wrong about this. Discuss it, bring your evidence on both sides — don’t ban the term!

Three examples of prejudice from the author’s life (and understand, I’m a 6-foot tall pale skinned Nordic-looking white man with blue-gray eyes and blond eyebrows & moustache who speaks articulately without a regional accent):

“Why don’t you go back where you came from?” asked an upset insurance agent after I’d turned down one of his clients. He was from the old upper class of Syracuse — much more laid-back than in my native New York City. Insurance underwriter was my first post-college job, and as a young, primarily Northern European-descended cis-gendered Christian white male with an Ivy League pedigree, I laughed it off — figuring it was OK for me to hear what so many others — immigrants, minorities, etc. heard all their lives. What I didn’t know then is that Autism was behind my undiplomatic bluntness. Other things I said later eventually got me fired from two insurance companies during a 5-month period! I had no idea I had a disability; it hadn’t been named yet.

When I first tried to rent an apartment in Syracuse, I was turned down by the downstairs owners of a two-family house. Why? They believed as a young single male, I would host loud drinking parties and have women staying over. Again, I had to laugh, because I’m a loner who rarely drinks alcohol, had no friends in town, never had a woman stay over during my time there, and can still count on one hand the number of parties I’ve given in my own home at any time in my life.

A favorite Chicago cousin was pushed toward vocational high school; his mother was told he wasn’t “smart enough” for an academic high school. He made a good living as a tool & die-maker, eventually starting his own business. His eldest son later became an accountant (a profession known for high intelligence scores), then Chief Financial Officer, then bought & ran manufacturing businesses! In hindsight, I think the dad was plenty smart also, but probably had an undiagnosed learning disability.

As for career choices for those with Autism, the quote Toe/ Hashtag gives at the bottom of page 23, “Genius does what it must, and talent does what it can,” is one of my (the author’s) favorites. Its source is a 19th Century English Politician, Edward G. Bulwer-Lytton. What I believe it means is that, for someone with Autism, it’s particularly important to discover which “special interest” one has that is good enough to lead to a career at genius or talent level. Which special interest both gives you joy and others say you do better than anyone else they know? If you have talents, but no true genius, figure out the combination of skills you have and seek an employer who needs just your particular combination of skills. Read the legendary job-seeking book, “What Color is Your Parachute? by Rev. Richard Boles.”

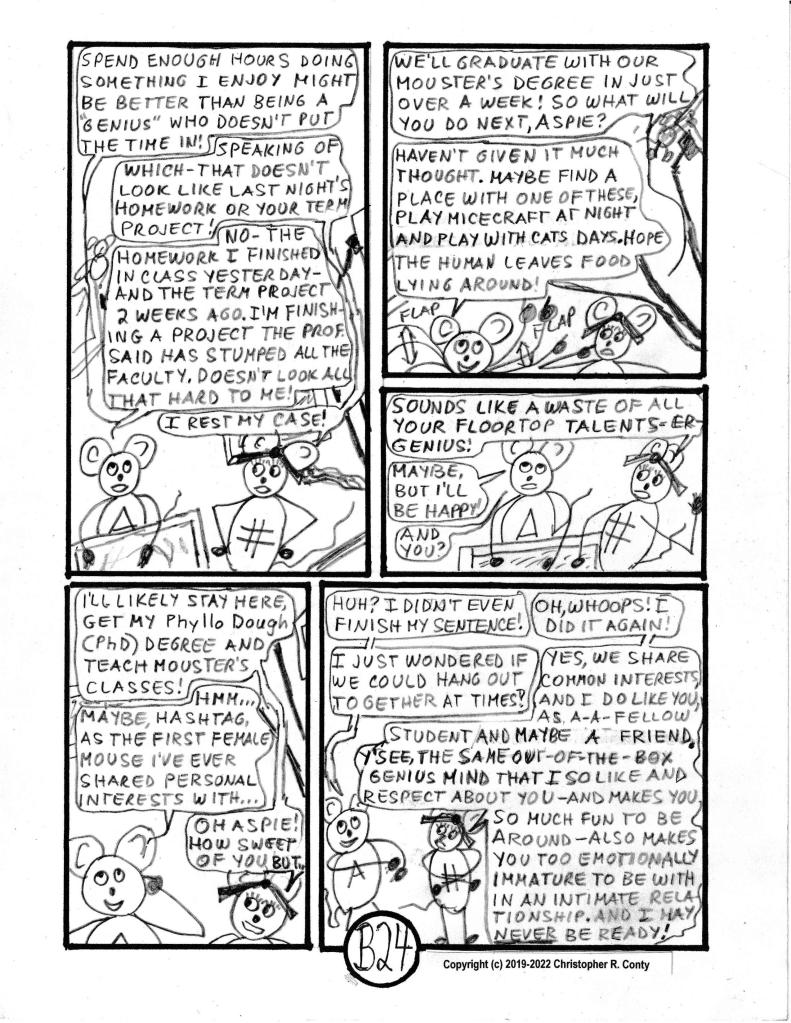

This author cautions against “envying” those with genius. I mentioned the above “genius/ talent” quote to Yo-yo Ma (famous cellist since 1980’s) once, and he dismissed it, saying Pablo Casals (famous cellist of mid-20th Century) first exclaimed when a rock fell on his hand while rock-climbing, “Oh good! I won’t have to play the cello anymore!” Aspie Mouse’s retort to Hashtag (page B-24) says that putting in the time can outrank genius — this is in line with Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that it takes 10,000 hours to attain true mastery. Toe/ Hashtag gets the last word, pointing out that Aspie Mouse has the arrogance to believe it’d be easy for him to solve a problem the mouse MIT moustructors couldn’t solve!

My (the author’s) father frequently said, “Get a profession — law, medicine, college professor, engineer, etc. — and then pursue something like drama, writing, music as a sideline, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did with Sherlock Holmes. And if it succeeds, great. If not, — so you have something solid to fall back on.” Sounds great — if one is both ambitious and Neurotypical! For me, it wasn’t good advice, because my day job took every ounce of energy I had just to exist. While I finally found a great fit for me in college textbook publishing — probably because so many college professors are also Aspies, and even those who weren’t could overlook my verbal gaffes — I needed bosses who’d protect me until my unorthodox methods finally showed results. For me, the best job is one where my results are clearly due to my work — not a “team” project. Temple Grandin recommends bringing a portfolio of your work to any job interview. While I had/ have a talent for helping authors write successful technical textbooks, the price I paid was setting my cartooning aside for decades, which I now judge was a mistake. And except for two jobs in my life (out of many), that first publisher was one of only two where I wasn’t fired or almost fired. My personal rate of unemployment during my working years? 50%! (Better than 75-80% typical of those diagnosed with Autism, but still…).

Other aspects of discrimination/ prejudice are discussed again in subsequent chapters — especially in Chapters F, G, H & I in Volume II — including at times race, gender, age, immigration and residence status, social class, and physical and mental health challenges. Question set B-9 is devoted to questions about prejudice/ discrimination based on Aspie Mouse’s Class 6 interchange with Hashtag.

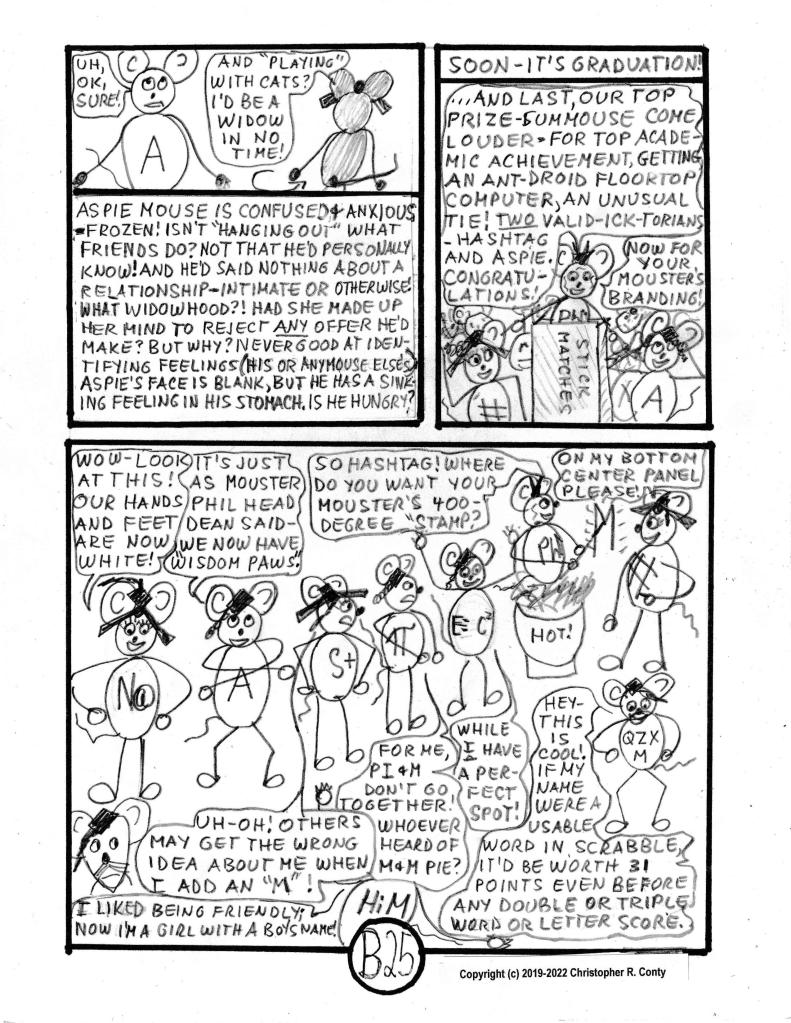

Stranger than fiction #1: On the last page of the chapter, Phil laments that when students graduate from the mouse MIT, they scatter without saying goodbye, hugging, etc. The basis of it: I, the author, was with a group of MIT alumni friends (though I didn’t go to MIT myself, I have more friends from there than from where I DID go to college, Yale: Autism-related, likely.) ending a celebration for an out-of-town friend’s visit. They just left, with no ceremony, no goodbye’s — much to the consternation of a Neurotypical woman present (she had her own abandonment issues); she couldn’t understand how they could just leave each other like that, when they might not see each other again for months or even years. The author later realized that many (maybe even most) Autistic people don’t see the need for long goodbyes. They’re glad to see their friends, and will be glad to see them again, but when it’s time to leave, they’re ready to move on to the next thing – alone! Get-togethers aren’t all that big a deal! And why bother taking the lead in organizing one? The irony is OTHERS with ASD feel lonely a lot (I was an only child, so I would try to “collect” friends, and to some extent still do), so they invite the “ho hum” Autistics to an event, where the “ho hum” Autistics (like my son!) often act glad they were invited (but if not interested in the event, may say no — the friend may not be reason enough); my son can be on the Internet for hours playing games, but when he’s called to dinner, he may just leave whoever he was playing with! Other places where Aspie Mouse & others show “ho-hum, OK, bye” behavior: Ch’s D, G, F & I. It’s addressed in Q B-11 (3 & 4).

Now for notes specific to the plot and panels of Chapter B and the Questions that follow:

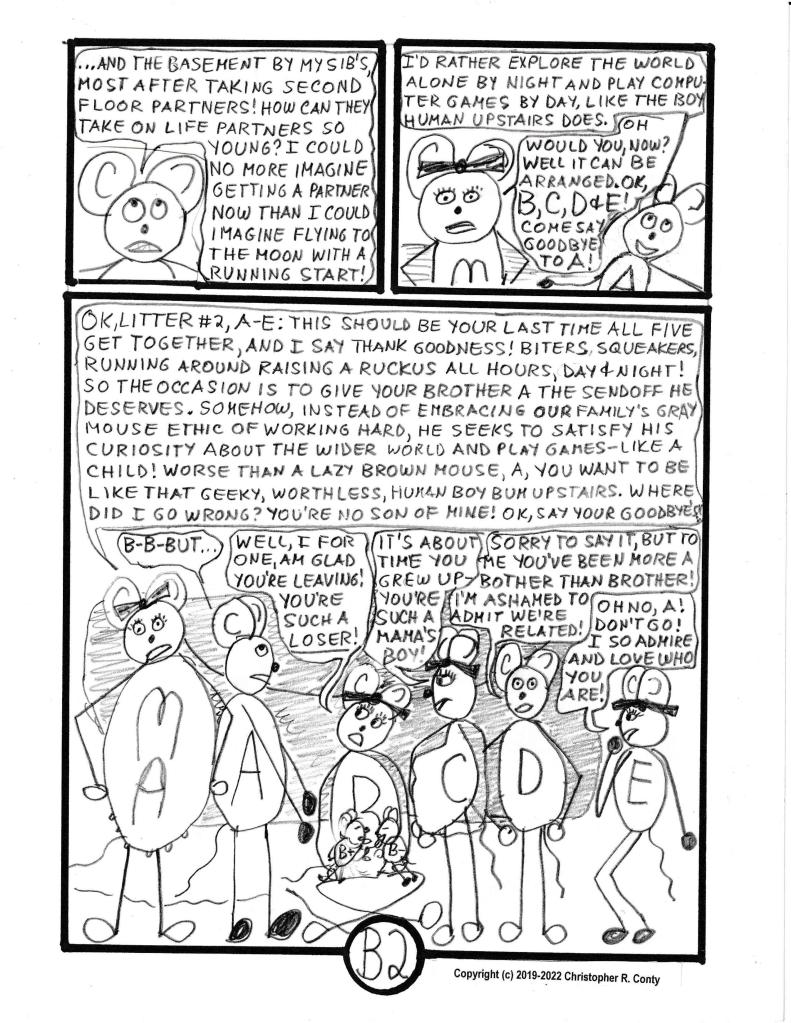

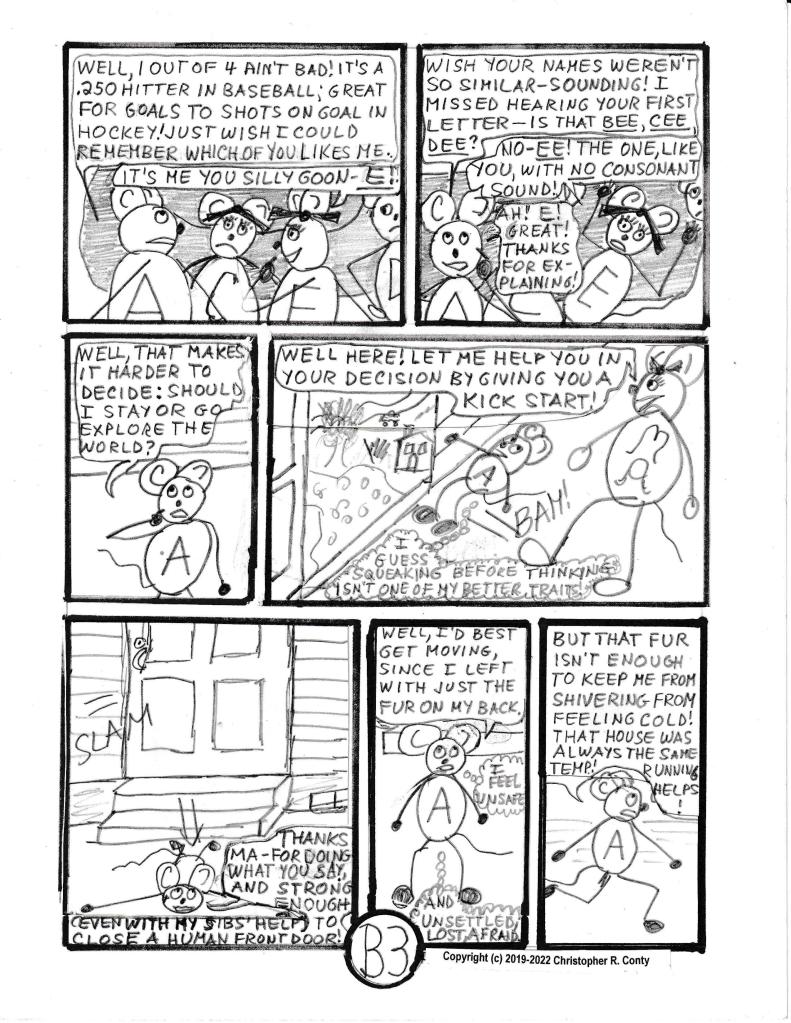

Chapter B opens with Aspie Mouse being told by his Momma that he was acting childish (still sucking on her breast for milk), while his siblings had grown up and were finding their way in the world. Aspie Mouse likes things the way they are, and isn’t ready to “grow up.” So Momma decides to kick him out, after gathering his siblings to bid him goodbye. We see for the first time Aspie Mouse stumbling with names, labels and faces, as he is unable to identify which of his siblings is which. Page B-3 has Aspie Mouse’s first “added thoughts” for this chapter, as to his internal feelings and insecurities — such as his tendency to “squeak” (speak) before thinking (no filter), as noted before in Chapter A’s notes and on page A-3, the author’s personal worst Aspie trait — and then feeling “unsafe .. unsettled, lost, afraid” after suddenly losing the only home Aspie Mouse has ever known.

Question B.2 asks readers to relate Aspie Mouse’s situation with his family home growing up to their own home growing up, and then Question B.3 asks about the reader’s relationships with parents and siblings. Similar questions will be asked in the next two chapters (C & D) when Aspie Mouse moves in with a human family of two adults and two kids.

While as noted above, Question set B.1 asks readers to use the 27 characteristics chart to identify all Autism traits shown in this chapter, Question B.4 focuses on Autistic traits of Aspie Mouse — and other Autistic characters introduced in this chapter — that aren’t shown in Chapter A. Q B.4-1 explores difficulty with names and faces (trait #23). Q B.4-2 discusses flapping and other “stimming” behaviors (trait #4). Q B.4/3-5 ask readers to comment on their own low self-esteem issues (trait #20), after Aspie Mouse raises them for himself, both vocally and to himself. Q B.4-6 addresses positive self-esteem: being rewarded for doing something well. Aspie Mouse will get several such compliments during his time at Mouse MIT — which may help explain his increasing confidence. See notes above for more about self-esteem. Q B.4-7 addresses special interests (trait #10 — though Aspie Mouse’s “interest” in playing with cats was already introduced in Chapter A), while Q B.4-8 addresses how learning disabilities can have a negative impact on self-esteem. See notes above for more about self-esteem.

After Aspie Mouse leaves home and escapes a cat, his desire for the safety of indoors leads him to stumble upon the Mouse “MIT.” The in-panel note at the bottom of page B-4 explains which animals can understand the speech of which other animals, even as readers are “let in” on all of it. This is separate from a few select animals that have a special ability to read others’ thoughts, and have those whose thoughts they “read” sometimes read theirs; this will be introduced in Chapter C.

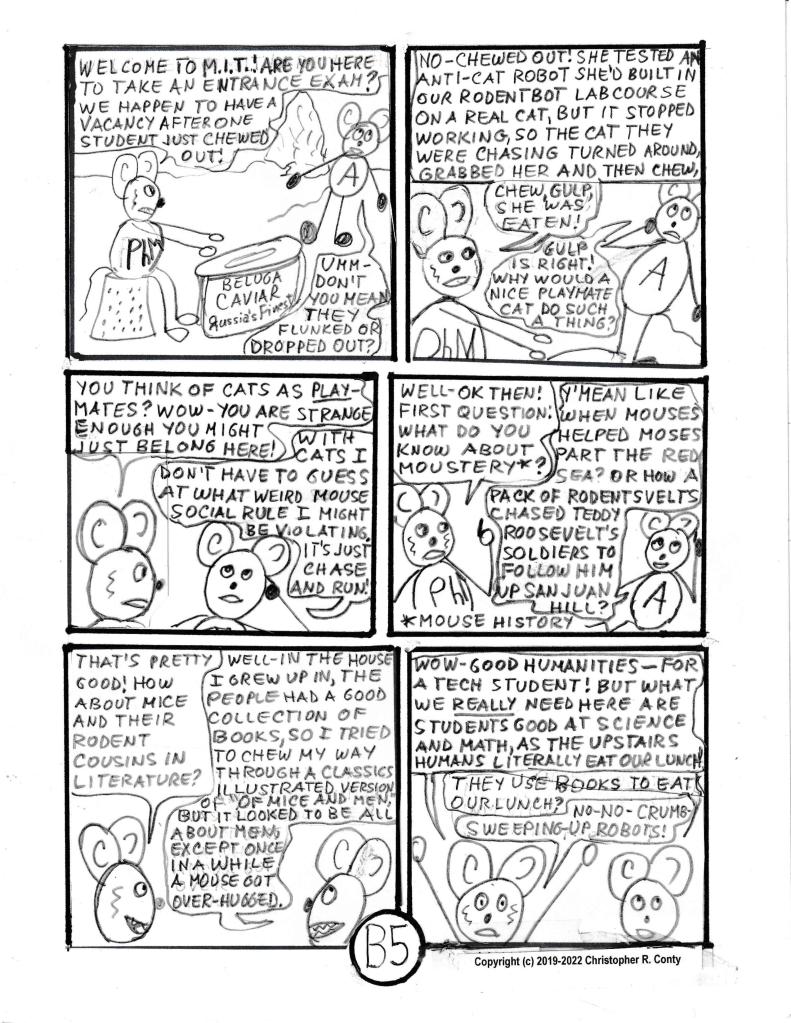

Pages B-5 to B-9 feature a clever back-and-forth between Headmouster Phil and Aspie Mouse as Aspie Mouse is in the process of get admitted to the Insqueaktoot (or what the human MIT students upstairs would call “the Institute”). Question set B.5 examines this give and take. Per notes above, Aspie Mouse tends to “take things at face value,” instead of realizing there may be a hidden deeper meaning beyond what’s said, including confusing “literally” with “literature.” Many “puns” and inside jokes during this interchange requires significant general knowledge: some strong reading Aspies will get most of them but poor reading Aspies whose interests are narrowly focused may not get many. Autistic readers who struggle to grasp deeper meanings of words and phrases are asked in Question set B.5 about the shame they may feel in not understanding — or even being laughed at. Looking up the ones missed for better understanding may broaden those Aspies’ knowledge. As with the “rules” of social understanding (trait #8), learning enough of these references can improve one’s ability to engage in conversations with others and not feel so foolish (trait #15).

I (the author) remembers being confused as a teenager when a bus driver said to a drunk man, “the NEXT bus will take you to New York,” and I asked in a panicky voice, “So THIS bus doesn’t go to New York?” My trip companion pulled me aside and said, “Yes it does — for US — but not for him!” Then I got it — and felt embarrassed that I hadn’t realized what was going on — that man wouldn’t be allowed on any bus to New York until he’d sobered up!

Once admitted to the Mouse MIT, Aspie Mouse gets acquainted with his fellow students, and, as their newest member, is asked to do a dangerous task: get the mice leftovers from a catered meal upstairs in the human university. And he’s asked to do so with three siblings — Tic, Tac and Toe. Question B.6 explores this most dangerous, and probably most interesting, part of the chapter, featuring another inter-play — this time between Aspie Mouse and Toe (who later in this chapter will rename herself Hashtag). Among the new Autism issues explored during this joint task: difficulties with teamwork — something those with Autism are usually poor at, preferring (per Trait #12 of the 27) working independently. To put it another way, Aspies prefer doing things by oneself as a loner or lone wolf. Note Aspie Mouse’s surprise in the upper left panel of page B-11 when he actually finds teamwork as somewhat fun!

Toe — clearly the smartest of the siblings — particularly dislikes working with others, given how often she’s been forced to team up with her not-very-competent brothers, Tic & Tac. Thus she’s dubious about Aspie Mouse. Toe also shows another Autistic trait right away: she lacks trust (Trait #21) of male mouse peers — especially those who, like her and Aspie Mouse, have Autism (again, given her experience with Tic & Tac). So the answer to Question B.6-2 is teamwork and trust — empathy might also fit, though Aspies often have more empathy for others’ emotional pain than most, even if they don’t trust those they have empathy for, don’t show or express it, and often can’t name what they’re feeling. The rest of Q B.6 covers prejudice (continued in more depth in Q B.9), how Aspie Mouse stays alive despite his “cat play special interest” and his picky eating again (also see Questions after Chapter A).

In not trusting Aspie Mouse as male and Autistic, Toe stereotypes him (bad side of Trait #9, pattern-seeking). Despite Hashtag constantly putting down Tic & Tac, when the two brothers go to an environment away from their frustrated sister — somewhere that may fit their real special interests, as they apparently do as this chapter proceeds — they might thrive (as even Hashtag admits)! As this chapter develops, Toe/ Hashtag gains respect for Aspie Mouse, but her feelings are complex. See below re Question sets B.9,10,11.

Question B.7 explores the peer relationship dynamics Aspie Mouse faces as he interacts with both fellow students and instructors in his courses — and at lunch. Because most Autistic readers of this work are likely to be attending school at some level, The first four Questions in B.7 focus on (a) a reader’s experience (like Aspie Mouse) in attending a new school with new peers; (b) how correcting a teacher (or a worker correcting a boss) usually doesn’t work out well for the student — because it embarrasses the teacher, who hates being “shown up” in front of class (wish I’d understood that!); (c) how correcting a fellow student — vs. letting the teacher make perhaps a kinder correction — can get someone Autistic in trouble with his peer classmates, which can lead to being shunned. The last four B.7 Questions (6-9) focus on traits mentioned early in the prior paragraph: how two potentially positive traits of those with Autism — problem-solving and pattern-seeking — can also lead to negative outcomes when (a) it’s a decision, not a problem, that’s needed; (b) when another person wants sympathy from another, NOT to help them “solve a problem”; (c) when pattern-seeking turns into stereotyping, a particularly thorny subject these days. Concerning (b), per Q B.7-9, when someone (often a woman, but not always) seeks sympathy or empathy (“Tell me how you feel”; “You look upset. Tell me what happened.” “Awww…”), but what they get instead is their partner trying to help “solve the problem,” the situation often escalates, and the “problem solver” is often confused as to why their willingness to help is rejected!

Question B.8 starts out (1-3) asking about table manners and other “expected” social behaviors, after showing how Aspie Mouse behaves at meals and in other social contexts, and goes on to ask readers how they think having habits such as poor manners — table and otherwise — affect employers’ decisions about hiring and promoting them. Temple Grandin makes a big point in her speeches that her first employer insisted she buy and use underarm deodorant! This author had a possible promotion to editor deferred for several months — despite being the most successful college textbook sales rep for five years — because at our lunch interview, the executive editor (future boss) was appalled at my table manners and that I’d ordered two desserts!

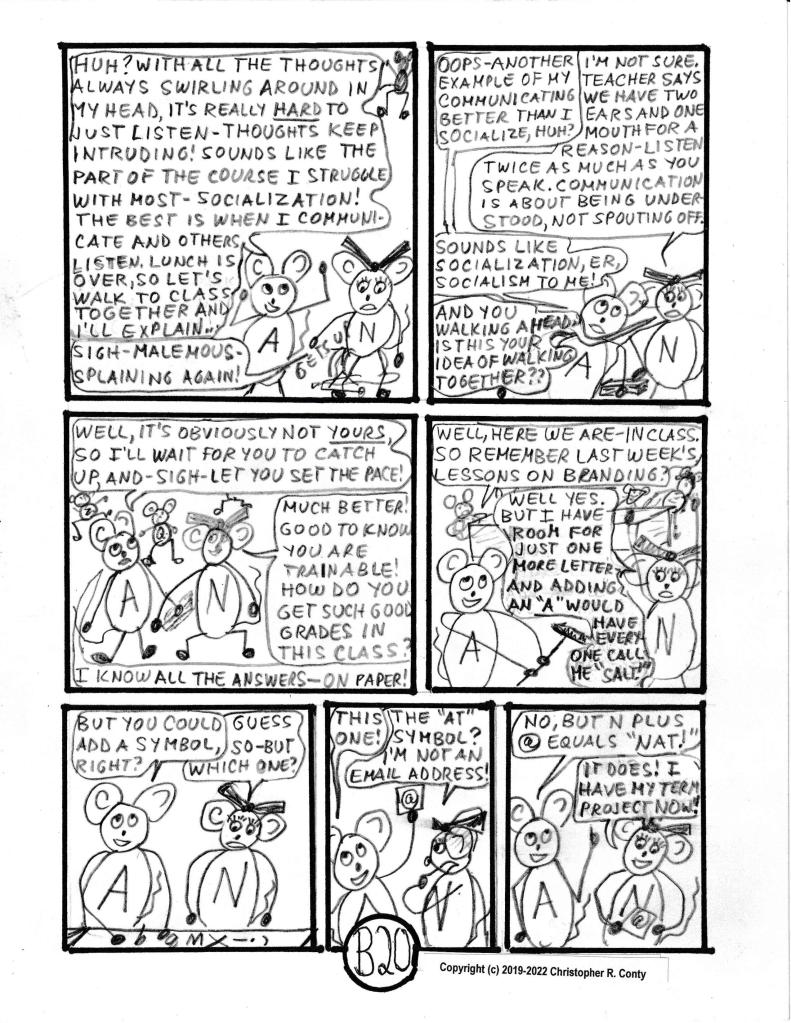

Questions B.8/4-7 concern what’s probably Aspie Mouse’s weakest course (also, as the instructor implies, true for most students here), Period 5, Inter-Rodent Communication and Socialization. Of course, social understanding (Trait #8) is a key area of struggle for almost all Autistic folks. While some with ASD are good communicators in terms of speaking and writing (such as I, the author), listening is rarely a strength, and even when it is, knowing when to speak and when not to can be challenging: (a) as “N”/ Natalie, Aspie Mouse’s lab partner from Period #1 implies about him in the bottom right panel on P. B-19); (b) as even when I (the author) am listening, if I interrupt, talk over, or seem otherwise occupied, whoever I’m with gets upset! Note that while Aspie Mouse also “talks over” Hashtag (page B23), Hashtag is similarly guilty of anticipating what Aspie Mouse will say instead of just listening (page B-24).

Question B.8-4 explores the “power dynamics” often at play between two individuals, usually one male and one female (who can be Neurodiverse and/ or Neurotypical) — in this instance Natalie and Aspie Mouse at the top of page B-20. This is an increasingly common complaint: a female perceives that a male is trying to dominate her verbally (even if unconsciously) by “explaining” something to her without asking first, apparently assuming she wouldn’t understand it as well as he does (“I’m smarter than you”) — often interrupting the female in the process. In human language, the term is “mansplaining.” So here, Natalie accuses Aspie Mouse of “malemousplaining” something to her. The problem for Aspie Mouse — and others with ASD — is that yes, they interrupt others when they’re speaking; and yes, they feel a need to explain something they know well (special interest); but they aren’t doing it to dominate others. Rather, it’s out of impatience to get their own words in, coupled with ignorance of social norms; they’re as likely to do it to another male; and extroverted female Aspies may do it to others regardless of gender. Q. B.8-4 is a good follow-up question to Q. B.7-9, about that common communication disconnect experienced by non-Aspies and Aspies alike as recently noted: one individual seeks emotional support, but the other tries problem-solving instead.

Questions B.8/5-7 continue in the same vein: what social communication & socialization “errors” can students spot, especially in the N/ Natalie-Aspie Mouse interactions? As for the female Autistic character doing a perceived “role reversal” (Q. B.8-5), it’s obviously Toe/ Hashtag. The trait I had in mind is mentioned in the top right panel on P. B-23, but you may also identify her doing all-or-none thinking & stereotyping (negative part of pattern-seeking).

Because Toe/ Hashtag is such a central character throughout this chapter — she reappears in Chapters G & J in Volume II — the interactions between her and Aspie Mouse first addressed in Question set B.5 continue in Question sets B.9,10,11. As this chapter develops, Toe/ Hashtag gains respect for Aspie Mouse, as opposed to her initial suspicion when she was first paired with him during the dangerous feast grab. However, a degree of suspicion/ antagonism remains.

The author cautions against “envying” those with genius, as when I (the author) said this quote to Yo-yo Ma (famous cellist), he said Pablo Casals (famous cellist of mid-20th Century) first exclaimed when a rock fell on his hand while rock-climbing, “Oh good! I won’t have to play the cello anymore!” Aspie Mouse’s retort (page B-24) is that putting in the time can outrank genius; this is in line with Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that it takes 10,000 hours to attain true mastery. Toe/ Hashtag gets the last word, pointing out that Aspie Mouse believes it’d be easy to solve a problem the mouse MIT moustructors couldn’t solve!

Question set B-9 references the Toe/ Hashtag-Aspie Mouse discussion around “discrimination/ prejudice.” Potential lessons are covered extensively in the general Ch. B notes above. The discussion begins in the last panel of page B-21 (their joint Class #6), with the most stinging lines appearing mostly on page B-22. Note the discussion also gets into race (why there are fewer brown mice than gray mice at Mouse MIT), privilege (which mice have access to “floortop computers”; how parental genes determine which mice get to be in lab experiments), etc.

If anyone believes discrimination against those with Autism — even though it’s a “hidden” disability” (not obvious visually in most cases, as long as one isn’t “flapping,” etc.) and therefore easier to “mask” — isn’t as bad for self-esteem as discrimination against age, physical disabilities, race, ethnicity, “national origin,” etc., give them this statistic: those with ASD “enjoy” a 75%+ unemployment rate. Even racial discrimination — the U.S.’s most blatant form historically — isn’t that high!

B-10 addresses general traits of Autism that Hashtag has, and how they differ from those of Aspie Mouse. Other female presenting characters with Autism will be introduced in Chapter E (a human girl) and Chapter F (a white multi-challenged cat).

Even while Hashtag’s lack of trust toward Aspie Mouse diminishes during the chapter, her general distrust of Autistic male mice continues in the form of fearing relationships, intimacy and even friendships. Question set B-11 addresses her confusion and fear about being in relationship with them in any form: friendships, partnerships, intimacy, etc. Of course this is a question all teens and young adults wrestle with; but it’s particularly full of landmines for those who have Autism. The misunderstanding these two end up having is based on conflicted — often unidentified — feelings (trait #7), which in turn also tie in with other traits, such as #5 (anxiety), #15 (naivete), #18 (logical vs. emotional), #19 (delayed emotional development), #21 (lack of trust) & #22 (over-sensitivity). Hashtag’s anxiety/ fear of/ discomfort with intimacy prevents her from agreeing to become Aspie Mouse’s friend, even though she behaves as if she already is! Exploring the Aspie Mouse-Hashtag relationship may help an Autistic reader become better at perspective taking, because how they relate to each other (which continues in Chapter G) is not simple. Sharing these thoughts with others in a class setting may be helpful.

Continuing on this theme, let’s return to the work of Carl Jung: he claims the four core feelings are sadness, anger, fear and joy (reinforced by many world cultures). Some say that love, hate and shame are separate feelings, while others think they are combinations of these four, and still others (such as “A Course in Miracles”) say all “feelings” of humans come from either love or fear. Thus, even as interest in someone as a potential partner — or even a friend — can awaken feelings of excitement/ joy and love — confused and/ or unidentified feelings also lead to feeling anxiety (fear). And again as per Chapter A, the responses to anxiety/ fear are fight, flight, fear or fawning. Thus Hashtag’s “explanation” as to why — though she may be ready to consider Aspie Mouse as a friend — she’s not ready to behave as a friend! It’s coming from anxiety; the response is flight — she’s basically running away from him. She’s also blaming his immaturity for her feelings; though she finally admits that she may NEVER be ready for an intimate relationship. As for Aspie Mouse — as poor at identifying his feelings as Hashtag appears to be — he wonders if that sinking feeling in his belly means he’s hungry. Sure seems more like sadness — even grief — in losing a love opportunity. This dynamic between them will resume in Chapter G.

Finally, Question set B-12 addresses the ending of Chapter B: the success that Aspie Mouse and Hashtag both experience; how Aspie Mouse’s family of origin might view his Mouse MIT success; and the strange way most Aspies depart after having a good time with each other in person (and probably also on screen): with little or no goodbye “ceremony.” See “Stranger than Fiction #1 at the end of the prior section of these notes.

27 Common Autism Characteristics, followed by possible questions related to Ch. B:

- No eye contact

- Sensory sensitivity: noise, certain lights, smells, touch/ textures, foods, hunger/ bathroom needs; physical space (stand too close/ far from others; need escape); creative, passionate re art, music, touch

- Self-Regulation: Speech: voice volume, repetition & variability; amount (see #6)

- Self-Regulation: Stimming – flapping, swaying, repetitive body/ hand movements/ head banging; use “fidgets”

- Anxiety (fear) & Overwhelm. Executive Function closes up > Meltdown: fight, flight or freeze. #1 barrier to ASD good mental health. Key: lower anxiety — yoga, meditation, count to 10, positive self-talk.

- All-or-None Thinking & Behavior: Say too much/ ask too many questions or say/ ask nothing; flat affect or too dramatic; not show or over-express feelings (see #7); avoid people or obsessed w/ some; loves/ overuses puns or humorless; substance abuser or teetotaler — extremes, no gray. Learn to sit in discomfort, seek middle.

- Difficulty identifying feelings; then not show or over-express them. Mistake not showing for not feeling & over-showing for “acting/ exaggerating.” Learn core feelings (mad, glad, sad, scared) & “not about me”

- Lack of Social Understanding, of others’ expectations (unaware). Ask for rules, put in writing and study as if taking school test. The core trait that drives the Adventures of Aspie Mouse: why his choices makes one laugh.

- Pattern-seeking/ solving problems in unique ways: why they’re inventors, good at “detail oriented” jobs; creative, intuitive.

- Special Interest(s) can pay off having unique expertise for work/ hobby. Great for self-esteem, relaxing, lowering anxiety.

- Independent thinkers/ most inventors; no/ weak peer influence/ expectations. Also a need to work independently as a colleague, not in a team structure. Needs trusting boss!

- Persistence once fully engaged; terrifying level of energy; not easily re-directed (see #16).

- Self-entertaining: If access to special interests, never bored; needs no playmate.

- Rule follower: conscientious once buys in; then helps enforce rules, offers improvements.

- Honesty, innocence, naivete: unusually truthful, will even tell on oneself. Positive side of “lack of social understanding” (see #8). Leads to trust, but seems too good to be true.

- Love routine/ dislike change and transitions: helps in self-regulation; holds on; loyal, slow to adjust, won’t jump ship.

- Unaware of impact of actions on others (adds to friction from #8): so invite feedback, don’t explain yourself.

- More logical than emotional: Makes for discomfort – Aspie of feelings; others for Aspie not expressing them.

- Emotionally delayed: emotional age 2/3-3/4 of chronological. Catch up slowly. Good to delay intimacy (honor your own clock).

- Low self-esteem: Stop self-blame! Give counter-messages: your unique strengths & you’re not at fault.

- Lack of trust, all feels unsafe: others’ trust/ safety priorities puzzling, why is my “feels right” labeled “unacceptable?” No! Unexpected! Choose your own safety priorities or those of others in household.

- Over-sensitivity > what’s said/ happens: over-reacts or no visible reaction (cares, can’t show it). Don’t take personally, let it go, Laugh about it vs. taking too seriously.

- Can’t remember names (even faces), read body language – not priority, can be by choice.

- Disconnected from body, including health, personal hygiene, need to eat/ sleep/ use bathroom, place in “space,” prone to self-injury (intentional & not).

- Extreme thoughts swirl inside mind, unrestrained by social norms; if spoken often leads to trouble, even if you’d never act upon the more scary thoughts. Challenge negative self-talk with positives and dismissal.

- Depression, suicidal thoughts, acts: anxiety & depression treated w/ same meds (body can’t tell difference); from low self-esteem, bad self-talk, sense of hopelessness. Get help, especially Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

- Hard to get & keep friends, jobs & relationships: to overcome, must work to lessen own & others’ discomfort. Listen! Show interest in others’ lives, passions & get feedback on your impact on them (see #17).

Questions for Thought/ Discussion: Ch. B, “Leaving the Nest for ‘M.I.T.

B 1: Relating the 27 Common Characteristics of Autism (above) to characters in Chapter B:

- To track the Autism characteristics that Aspie Mouse displays in each chapter of these “Adventures,” you might want to use a spreadsheet such as the one below. (Find it as a spreadsheet for Chapters A-I elsewhere on the Aspie Mouse website). Aspie Mouse is always listed as the first character for each chapter in the spreadsheet.

- More ambitious readers are invited to do the same for other Autistic characters, especially those at the Mouse “M.I.T.”

- Particularly devoted readers may use + and – signs to indicate when a particular Autistic trait is shown positively, negatively or some of each.

- Which Autistic trait(s) shown in this chapter do you identify with? Do you see each trait as more positive, more negative or roughly balanced? Insert a column for yourself!

- Which Autistic traits shown by characters in this chapter are not traits you have, whether you’re Autistic or not?

B 2: (Similar to Q D.2) Aspie Mouse likes where he lives, but Momma wants him out.

- What do you like about where you live? Dislike?

- When do you prefer being alone? When would prefer being around other people?

- Which specific person or people (if any) would you rather be around most or all the time — besides yourself? What makes you feel comfortable being around that person?

- Are you (or if still in school: Do you plan to be) living on your own — vs. staying with your parents (after you finish your schooling)? Which would your parents prefer that you do? If these wants are different, does it cause stress, and how do you handle or work through that stress?

- Do you judge your parents understand your needs in terms of having Autism? Or if you don’t have Autism, answer this question generally (do your parents understand what you need)?

- Do you think you have tools to explain who you are, if they initially didn’t “get” you? How much do you understand who you are? The author was well into adulthood before he finally had a fairly complete picture as to who he was and is.

- How did you react to AM’s mom literally “kicking him out” of the house? What feelings came up for you? What do you wish AM could do or would do instead of “taking it” — or are you glad for him, seeing how he ended up after being kicked out?

- After reading this chapter, explain why does Aspie Mouse’s sister “E” has dark paws in the bottom panel on page B-2, while his Momma’s and other siblings’ paws are white?

B 3: (Similar to Q. D.3, referring to human siblings) Aspie Mouse lives with four siblings: brother D, & sisters B, C &

- If you live or lived with one or more other children growing up, especially if one or more are non-Autistic (Neurotypical), how do/ did you and they get along?

- Same situation as B.2-1 above (grew up with other kids, Autistic or not): Was there jealousy — complaints about fairness — about parents’ treatment about achievement, abilities, success, attention, and how rules were applied to you vs. them? Do/ did such complaints go both ways, or did you or another child complain a lot more, at least in your memory? Would the other child(ren) likely agree on who complained more?

- If you’re an only child, did you wish you had a brother or sister or both? How might life have been different? If you grew up with other kids at home, did you often wish you were an only child? How might life have been different? If you’re in a group to share these responses with, are you surprised to hear how the situation different from what you experienced was for those other(s) growing up?

- Did you experience comments like Momma Mouse makes to all five siblings — that she’s glad to get rid of them because they fight so much, etc. from your parents? If so, how has it affected you? If not, are you now grateful they didn’t? How might comments like that have a lasting effect on someone’s self-esteem (how they feel about themself)? What might be a better way for Momma Mouse to handle her frustrations other than insulting her newly “grown-up” offspring as to how they were as youngsters?

- (Will go into further depth with this subject in Question D 3, 2 chapters later, and again after Ch. H): How do you think Aspie Mouse feels when 3 of his 4 siblings call him “names” and say they’d rather he be gone? Has this been an issue between you and your siblings (if you have) and/ or schoolmates (name-calling)? How have you handled it?

- Do you believe sibling issues are different (better? worse? the same?) in homes where none of the children have Autism or other situation where some of their brains operate differently from most people’s?

B 4: Aspie Mouse shows Autistic traits in Ch. B not shown in Chapter A (as per Q. B.1).

- Aspie Mouse has trouble remembering names, even with their initials on their chest, for both his sister E and “Head Mouster Phil.’ Is remembering names a problem for you? All the time or only at certain times? Do you mix people up or not recognize faces (often, seldom, never)? If these are problems for you, how do you “cover up”? When someone can’t remember YOUR name, does it bother you? Do you think they don’t care about you?

- Aspie Mouse is quite smart and rather good with spoken words, but has trouble reading letters, especially if they’re not being used in words, but just initials. Do you have reading issues, word usage issues or another “learning deficit/ disability?” Did you know they’re common for “Aspies”? What techniques do you use to make up for/ hide your confusion?

- We see Aspie Mouse “flap” when he gets excited (3 times: can you locate which pages?). Is that a trait you have? How else might you physically show Autism in terms of movement (swaying back & forth, throwing head back, etc.). If you don’t have Autism, does this disturb you? If you do have Autism and don’t have this trait, does it disturb you? If you have Autism, does your OWN movement trait(s) bother you? Why do you think the others at the Mouse MIT don’t comment on Aspie Mouse’s flapping?

- Aspie Mouse also has low self-esteem (doesn’t feel good about himself), based on how his mother and three siblings treat him when he’s leaving. He admits to Head Mouster Phil that his family thought AM was a “moustake.” Do you have “low self-esteem” issues? Who told you, either obviously or by deeds if not words, that you aren’t “good enough” as you are? Has it made you a better person or made it harder for you to gain confidence? Or are you one of the lucky folks not to be “put down” by your parents? How can you counter “not good enough” messages in your head?

- What do you think of the idea — popular with many adult “self-help programs” — that when other people complain about “who you are” — not how you behave (which is fair, especially if it focuses on how your behavior impacted them) — IT’S ABOUT THEM. Might it be something they don’t like about THEMSELVES, but they blame it on you because they don’t want to see it in themselves?

- (Continuing from B.4-3 & 4): Being told “you ARE a mistake” can be very damaging. What’s the key difference between believing that “I AM a mistake,” instead of “I MADE a mistake”? Shame from “I made a mistake” is appropriate; shame from believing “I am a mistake” is toxic/ deadly and NOT TRUE! Nobody is a mistake.

- Have you had something good happen — as when Aspie Mouse is admitted to “M.I.T.” — that shows you are very much wanted in this world and do something well? Whether you’ve had that experience or not, how may you overcome others’ negative opinions of you, or decide not to let them rule your life?

- Do you have a special interest that isn’t always appreciated by others who know you well, such as Aspie Mouse has in making language translation apps?

- This is the first of many chapters dealing with Anxiety, which is widely experienced in society, not just by those with Autism However, 98% of Adults with Autism self-report it as an issue, more than any other trait. When those with ASD are more anxious than usual, they tend to be either very animated — making extravagant gestures, speaking loudly, talking on and on, and asking lots of questions — or they get very quiet, make few if any movements with their heads and face, don’t look at whoever is speaking to them, and don’t ask questions — even if they’re totally confused. If you’re on the Autism Spectrum, which end of this are you most like? Whether or not you have Autism, why do you think the just-mentioned behaviors might lead to others being frustrated or not trusting you/ them? What might someone with either type of Autism responses to anxiety do to help others trust them more? (Related anxiety questions appear in Ch. C & D Question sets)

B 5: When Aspie Mouse stumbles into the “Rodent MIT,” he has to pass an admissions “test.”

- When Aspie Mouse tells Head Mouster Phil he likes to play with cats, why do you think Phil’s response is, “… you are strange enough, you might just belong here?” Have you ever found a place where people with Autism are actually preferred or in the majority? How did that work out for you? If you haven’t found such a place, would you like to find one?

- When Phil asks Aspie Mouse to recreate his human-rodent programming translation, he was astonished how quickly and how well Aspie Mouse did it. Do you have a special interest that when you show it to the right people gets an impressive and astonished response? If not, do you have some interest that you feel good enough about, that you believe helps your self-esteem and could eventually help your career prospects?

- Aspie Mouse takes Headmouster Phil’s words “I’m pulling your leg” literally, not seeing it as an idiomatic expression. Then, when told he’s being “too literal,” Aspie Mouse assumes Phil’s talking about him reading too much literature, a running “gag” throughout this work. When have you thought someone was saying something you took at “face value,” when they were just using an expression or idiom? What problems have occurred when/ if you didn’t recognize when someone was being ironic or just using an “expression”?

- In confessing he was “pulling AM’s leg,” Head Mouster Phil was covering up some shame. Do you ever “add” to the truth to cover up shame? Or do you just say nothing? Or do you just lie? How do you deal with shame? What works to combat your feelings of shame?

- Throughout the chapter, AM can’t keep the order straight of Head Mouster Phil’s name. Why do you think Headmouster Phil didn’t comment on that to Aspie Mouse?

B 6: Once admitted to “MIT,” Aspie Mouse is asked to be on the team to get dinner from “upstairs.”

- Toe/ Hashtag has a very negative attitude toward Aspie Mouse because he’s male. Why is she so negative toward male mice, from what we can tell? What helps change her mind about Aspie Mouse?

- What are two of the 27 Autistic Characteristics that fit Toe/ Hashtag’s negative attitude toward Aspie Mouse? Hint: What aren’t those with Autism good at doing that she’s being asked to do with Aspie Mouse and her brothers? Another hint: What do you lack when you feel negative toward someone?

- Have you experienced someone who has a “prejudice” against you because of anything (race, gender, Autism, etc.) and were able to “overcome” that prejudice? If not, did you try or did you just avoid that person? Have you been prejudiced against someone else and changed your mind? Why or why not?

- Why do you think Aspie Mouse manages to stay alive despite believing cats make great playmates for him — at least in this chapter? Do you do anything “dangerous” that leads to others seeming more afraid for your safety more than you are?

- Aspie Mouse is “rewarded” for getting the food — but he said he’d rather have a different food reward. Do you have very particular food preferences, as AM does, or do you eat pretty much everything? What do you think accounts for whichever way you are around food? What problems did you have being younger if you have particular food preferences? Have you become more open to foods you didn’t like when younger? How did that happen if it did?

B 7: Aspie Mouse needs to “catch up” with the other rostudents because he’s starting classes two weeks after the beginning. He seems to be doing pretty well.

- Have you been transferred to a different class, school or situation where you were starting from behind? How well did you handle it? What support did you get if so? Also if so, what support did you need that you didn’t get?

- Notice how for the first three morning classes, and the middle class in the afternoon (#6 of 7, “Pleasing Professors … Pellets,”) Aspie Mouse reacts sarcastically to the title of the course, who’s teaching it, the equipment being used in the lab, etc. Does he seem to realize — or care — that he’s offending these course instructors? Explain how Aspie Mouse sometimes overcomes the instructor’s anger over his “fun-making” — by “putting his money where his mouth is.”

- Have you gotten in trouble or gotten bad reactions from teachers or others — for what you said about a class? Are you then able to overcome your unfortunate comments by doing things that make up for your verbal goofs? Have you tried to correct a teacher in front of a class? If so, how did that go? Do you say things like these and then later feel shame? What’s a good way to reduce the shame?

- Have you tried to correct another student’s comments in class, before the teacher could or before being asked? If so, how did that go? Do you think you may have lost a friend or potential friend for saying something in a class or other group social situation that may have made that other person feel bad? What might be a better way for you to offer constructive correction to a teacher — or a fellow student — instead of speaking out in class or in front of everyone? Again, did this lead to shame?

- Did you anticipate how Aspie Mouse would “solve” the problems presented in the first two morning classes before he solved them? Is this kind of “out of the box” problem-solving something you’re good at? Did you anticipate how AM might try to make his “grab your own lunch” process easier before he did it?

- In what areas are you particularly good at solving problems that seem hard for other people, but not you? In what areas do you struggle solving problems that others seem to solve more easily? How do you react when you struggle at what others find easier to do?

- Another trait very often found in those with Autism is pattern-seeking — which can often lead to solving problems in unique ways. How does Aspie Mouse show unique pattern-seeking abilities in this chapter, especially in classes? How have you benefited from pattern-seeking behaviors in your life (if you have)?

- Pattern-seeking also has a negative side, especially when we to put people in boxes or categories based on race, national or regional background, gender, name, etc. What are examples of Autistic characters doing this in this chapter (about mice especially, but maybe also about people)? What are examples of non-Autistic characters doing this (because non-Autistic people have been doing this to other people for a long time)? How has trying to put people into categories caused problems in your life? What might you do to break this habit — especially with people? At least, what can you do to avoid offending others (how to keep your thoughts about this to yourself)? Why is it important NOT to put people in categories in today’s society?

- Ever have an interaction that goes bad? Someone (often a woman) says to their partner, “I had a hard day. This is what happened…” If the partner responds with, “Let me help you solve your problem,” things are likely to go bad quickly, with the first partner getting angry with the second. Why? How should the second partner respond to the first partner so things go better?

B 8: Aspie Mouse also interacts with his peers in his classes and at lunch. Displaying bad table manners and lacking awareness of how his behavior affects other mice, AM ends up in some awkward situations.

- How does Aspie Mouse try to explain away his bad table manners? Why do other students seem willing to put up with his lack of table manners and eat with him anyway?

- Do you struggle understanding the importance of table manners, good hygiene (bathing, grooming, use of deodorant and breath mints) and other unwritten “rules” of conduct in social situations? Do you understand how it could affect the outcome of job interviews and retaining employment? Or are you glad your parents instilled good table manners, hygiene & other social norms into you, whether or not you saw the point of it at the time?

- Show examples in this chapter where Aspie Mouse’s positive Autistic traits help overcome the poor social skills he shows at lunch and in his classes.

- In his fifth class (first after lunch), “N” (Natalie) “accuses” AM of “Malemousplaining” (for people, it’s called “mansplaining,” where men seem to assume women need them to explain something — without ever asking first. If you are male, do you have a tendency to over-explain things, especially to females? If you are female, do you have trouble with males who keep talking and not listen enough? Or do you see the opposite — women talking a lot more? If you identify as other than male or female — or you’re trans — what’s your experience with this issue?

- On the other hand, can you find an example in this chapter of a “role reversal” — in which a negative social trait often associated with males is shown by a female on the Autism Spectrum?

- Also in the fifth class (Inter-rodent Communication and Socialization), Aspie Mouse’s dialogue with “N” reveals many instances of the social “cluelessness” that AM really struggles with. How many can you identify? Besides his obvious “lack of social understanding,” what OTHER related Aspie traits does AM show in his responses to “N?”

- Which of Aspie Mouse’s difficulty with social understanding in his fifth course (ICS) can you identify with? Which of them are really obvious in others? What ways do you use to reduce or limit the number of times such misunderstandings occur?

B 9: Aspie Mouse has several interactions with Toe/ Hashtag in their shared last two classes of the day. In this and the next question (B-9), questions about their interactions will follow. We start with their 6th Period Class, “Pleasing Professors to Produce Pellets.”

- Why did Aspie Mouse originally sign up for this class — what did he think he’d be doing afterwards? Why did Hashtag sign up for this class? Who is disappointed and why? Who isn’t disappointed and why?

- Toe/ Hashtag says she thinks AM isn’t “grateful” enough. Why? AM disagrees. Why?

- How did you react when Aspie Mouse said he couldn’t be a lab mouse because he’s gray, whereas lab mice are all white? Does he have a point? Does his complaint remind you of anything in the human world?

- What reason(s) does Toe/ Hashtag give for why AM is not a suitable lab mouse, beyond any issue around color? What’s AM’s reaction?

- Summarize the final reason/ argument Toe/ Hashtag gives for discouraging AM for wanting to be a human lab mouse (on p. B-22 lower left panel, following “besides …”) in a simple sentence of 10 words or fewer (even better if as few as 5 words).

- Toe/ Hashtag is well-meaning when she discourages AM from becoming a “lab mouse.” But how might someone use the Question B.9-5 argument to discourage someone else from: buying a house or renting an apartment in a given neighborhood/ applying for a job or to go to a prestigious college/ high school, etc.?

- How might using this argument or story take attention away from or justify (make seem reasonable; help disguise) discomfort/ prejudice that the person in power has — about something superficial like race, gender, ethnicity, age or disability — about the applicant? Then how might the person in power use that argument to discourage an applicant (for the house, apartment, job) from moving forward?

- Have you experienced or known about such an argument used to discourage anyone in your or your family from moving forward in buying, renting, applying for a job or educational program? If you’re ever given that argument and (unlike AM) you believe it should be challenged, how might you do so?

B 10: Continuing with other Aspie Mouse/ Toe-Hashtag interactions toward the end of the chapter in their last class together — Mousatronic Floortop (Human Cell Phone) Programming Lab :

- Toe/ Hashtag claims she also has Autism, though unlike AM, she looks others in the eye, thus seems more socially connected. Autism often is harder to detect in females vs. males. Why do you think Autism in females may be harder to detect than in males?

- What trait(s) do you see in this chapter that show Toe/ Hashtag does indeed have Autism — if any?

- Aspie Mouse seems to overlook negative traits of others with Autism. Why do you think he does? How well do you overlook others’ negative traits? Why do you think you find that easy/ difficult to do? Do you find yourself comparing “how Autistic” you are versus others with Autism? Why is doing so either good or bad in your judgment?

- What common trait of many with Autism is Toe/ Hashtag not considering when she gets upset with AM for calling her “Toe” instead of “Hashtag?”

- What do you think of the quote Hashtag uses at the bottom of page B-23, “Genius does what it must; talent does what it can?”

B 11: The last interaction Aspie Mouse has with Toe/ Hashtag (pages 24-25) addresses the important issue of “miscommunication” between two folks with Autism, when both are having strong feelings, but having trouble identifying those feelings.