Notes meant to be read prior to reading Chapter Pre-A, Introducing Aspie Mouse

This preface (masquerading as a chapter) for The Adventures of Aspie Mouse is aimed at teachers and parents. However tweens, teens and young adults, both on the Autism Spectrum and “Neurotypical,” are certainly encouraged to read it. It’s a good short intro to what mid-range Autism is all about — especially in focusing on its advantages — encouraging readers to make the effort to find work-arounds and develop a positive self-attitude. Autism’s challenges are not minimized — if anything, they’re sometimes exaggerated. But these challenges don’t prevent Aspie Mouse and other Autistic characters from thriving (not just surviving), because they’ve mostly figured out what works to: lower anxiety in a good way; develop a positive attitude toward themselves; and make good use of the gifts Autism has given them.

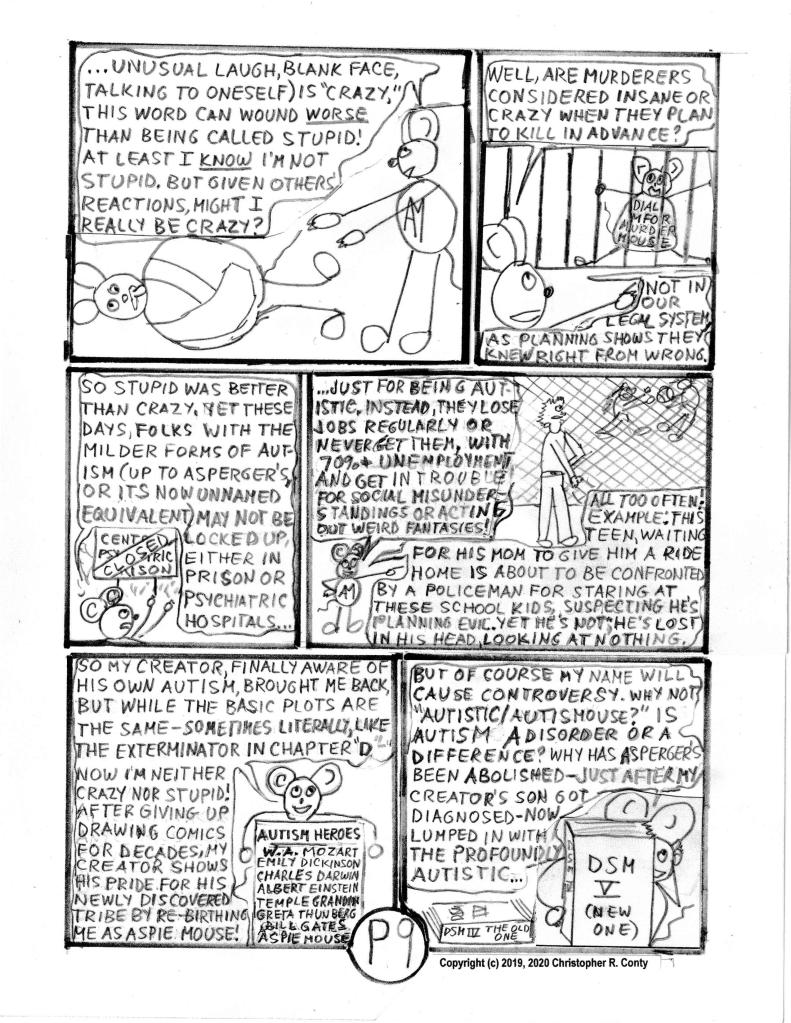

This is a graphic novel, not a handbook or resource guide to treating Autism. So, neither causes nor treatments/ remedies for Autistic behaviors get much attention beyond this preface. Even then, causes and/ or treatments are noted as to how one of the 27 identified Autism-related traits discussed relates to one or more other Autistic traits/ behaviors. Most folks read books that are fun, rather than those that are “good for them.” So Aspie Mouse’s adventures are designed to be entertaining, with lessons only rarely spelled out in the panels of the nine following chapters. It’s like making pasta from spinach: the “good for you” aspects are hidden.

Some of the more seriously disabling characteristics sometimes found in those with Autism — such as depression, suicidal thoughts, self-harm, etc. — are kept to a minimum. When they do appear, characters support each other to consciously convert these negative thoughts into positive responses in their behavior. It may not be clear how they do this — because remedies (there are no cures!), like causes, are beyond the scope of this graphic novel.

The real “enemy” for those with Autism is the high level of anxiety (a persistent form of fear) that shuts down “executive function” when triggered, such that one’s usual resources seem to disappear, leading to a “meltdown” (fight, flight, freeze) response. Successful Autistic characters in these adventures have found ways to look at anxiety-provoking situations as “exciting,” rather than overwhelming; they avoid having a meltdown, and instead use their creative powers to find unique ways of resolving what most would consider stressful dilemmas.

The main protagonist in primarily showing such positive aspects of Autism is Aspie Mouse, the Autistic Lead Character (a first for a graphic novel?). Along with other supporting characters –Autistic, Neurotypical and those with different mental health profiles (especially “enemy” types who take too much joy in causing others pain and grief) — Aspie Mouse models attitudes and behaviors for Autistic readers to consider how they too might: lower their own anxiety in constructive ways; live comfortably in their own skin; improve their “social understanding”; and succeed despite living in a world that really doesn’t “get” them.

Even Autistic traits usually viewed as mostly negative are shown to have useful positive aspects — especially those behaviors that help reduce anxiety, even if only temporarily. Non-Autistic readers may also find some of these same tools useful in their own lives. Plus, non-Autistic readers — seeing Autistic characters doing positive things in the world despite so much push back against what the greater society says are unwanted, unexpected behaviors — may develop more empathy toward those with Autism in their own lives. Both groups may better understnd how these puzzling behaviors were developed by those with Autism as a defense against both crippling anxiety and social expectations that are difficult (sometimes impossible) for those with Autism to meet. Mutual understanding is the goal here.

Aspie Mouse (especially) often makes decisions without regard to social norms, creating amusing — even dangerous situations — but gets out of them. Usually it’s because he doesn’t realize the trouble he’s in, so the paralyzing anxiety of Autism isn’t brought on. Instead, he sees patterns others don’t — thus his response to anxiety is instead to zero in on what’s really going on, pay careful attention (it’s called “hyper-focus”) and draw on his ability to solve problems in unique ways. When others then call him a hero, he is genuinely confused: he was just trying to solve a personal problem, mostly unaware of the often greater positive impact his pattern-seeking problem-solving actions have on those around him. When his impact isn’t so positive — such as near the end of Ch’s. A & H — it’s made clear that he means well, yet ignores the signs as to how his desire to have fun is at others’ expense. It’s a key problem for those with Autism: the difference between intention (good for all) and impact (other(s) are rightfully upset).

Why does Aspie Mouse has a dangerous “special interest” playing with cats? It’s a way to lighten things up, turn the tables on expectations (cats are supposed to go after mice, not the other way around!) and give a glimpse as to how different the thoughts and desires of those on the spectrum can be vs. the norm. It’s entertaining — fun! — to watch Aspie Mouse bamboozle and befuddle cats who don’t understand why they just can’t catch a mouse with no evident super-power — yet he keeps not getting caught, is apparently unafraid, and even invites them to chase him! For Aspie Mouse, playing with cats represents excitement. It’s what sky-diving, sports contests, amusement park rides, and what police, firefighters and EMT’s do for many people (including those with Autism and ADHD): experience the positive excitement of focused attention and high adrenaline (good anxiety), without going into the paralyzing out-of-control lows of crippling anxiety and depression.

Why is Aspie Mouse male — and straight — during an era when non-white, female and LGBTQ heroes are so highly sought to bring balance to what’s been written for generations? Simple: he’s an avatar or alter ego for the author — who is also male and straight — and white — though Aspie Mouse is gray in a world of gray, white and brown mice. I’m writing what I know!

However, several characters — Autistic and otherwise; human and animal — are from other genders, sexual orientations, and various ethnic and racial identities. This isn’t tokenism, but very much reflects this author’s personal life experience with people from varied backgrounds — starting with two African-American brothers I met at age seven, to whom this work is dedicated. It’s so dedicated because of their influence on my cartooning.

That personal experience continues as I incorporate traits from people I’ve known over the years who are Asian, Hispanic, Jewish, Catholic, Protestant & Islamic; and from Italian, Irish, Scandinavian, West Indian, Russian, Ukranian, Colombian, Japanese, etc. backgrounds, into the story. I also have inter-racial, gay and bi-sexual family members and friends, including at least four trans individuals I know personally, all of whom I also knew before they declared their change and began transitioning.

In choosing which ethnic/ racial groups should be represented for my human characters, I thought carefully as to what ethnicity/ nationality/ race might make the story richer for their presence in a particular chapter or situation. I am not intending to take sides here in the culture wars, though my choices may have consequences, such as keeping this graphic novel out of some socially conservative school classrooms and libraries. But here’s the dilemma: people on the Autism Spectrum — like me! — don’t usually buy in to local social norms — to them, these “artificial” rules just seem silly. A key purpose of this work is to improve self-esteem for those with Autism by showing them that their “non-social” (vs. anti-social!) thoughts are OK to have. However — and here social conservatives may agree with me — having these thoughts is very different from acting on them! So Hashtag may be confused about her sexual identity, but so far, she’s chosen to “present” as female — partly out of comfort, but also to avoid making waves that could jeopardize her employment. This is a real issue for many with Autism!

After all chapters were finished in draft form (including major updates for Ch’s. B & C), I decided to completely rewrite this preface (except for the first page!) to put in context 27 Characteristics of Autism that appear in the Question sets for the other nine chapters (after each chapter in this blog; will be separated from the panels in the final print/ e-book version). Because the revised 32-page preface is so different from the prior 12-page version, the author is keeping BOTH versions of the preface in the blog for now. The new preface is given first.

What’s become clear as the last few of the 27 characteristics are explored is that there have been too few examples showing how Aspie Mouse’s thought process, in which his natural Autistic tendencies get consciously modified (because he’s “excited” vs. over-anxious) to a more creative/ effective plan of action, thus improving the outcome for — and impact on — those around him. That will be fixed — along with some other last-minute tinkering with the nine “action” chapters — next, now that this revision of Pre-A is complete

These prefaces are purposely “re-published” as the latest “chapter,” because feedback is really desired. Do you like the old preface better? What should be cut to shorten the new one? What’s missing in the new one that should be imported from the old one? Thanks!

Chris Conty, Author, April 25, 2022

What follows is the revised original preface (from fall, 2020):

It’s very important, from my (the author’s) perspective to make it clear over and over to readers that Brilli the cat is NOT Autistic! She has an Antisocial Personality Disorder. Period! Yet, as noted in the pre-chapter notes, as with many (most?) non-Autistic folks, both Neurotypicals and otherwise “disordered,” Brilli has traits also common to those with Autism. After all, Autism IS a spectrum! As noted in the pre-chapter notes, negative self-talk & anxiety are found in others besides Aspies, though fear/ anxiety more often energizes APD’s such as Brilli, while crippling Aspie’s. Another trait found in some Aspies (the extroverted ones) and also in Sociopaths (though not Psychopaths) is being overly emotional and overly dramatic (vs. Aspies who speak in a monotone and show little emotion and Psychopaths who are trying not to draw attention to themselves). Another: almost all Aspies and Sociopaths find it difficult to take another’s perspective, especially in terms of relating to how another feels — or even how they feel! The key difference: sociopaths use these behavior traits in a calculated way to get what they want — and what they want is usually control — in a very bad way for whomever they want to control — whereas for those with Autism, these things just happen; there’s no antisocial intent. While Psychopaths are good at figuring out what motivates another person (Aspies usually have no clue), they lack empathy, which Aspies usually have, though they often don’t show it.

This is a good time to note the difference between a tantrum and a meltdown. A tantrum may be calculated to get a desired result — sociopaths create tantrums to manipulate or frighten those they want to control. Whereas a meltdown just happens as a result of elevated anxiety and a shutdown of executive function — that’s what Aspies experience. Meltdowns come in at least three varieties in response to fear or anxiety: fight, flight or freeze, as per below (Source: Been There, Done That … by Tony Attwood, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2014)

So is it possible to have Autism AND be a Sociopath? Rarely, though perhaps possible. Autistic and a Psychopath? Virtually impossible! Psychopaths are very adept at “blending in” with society, whereas those with Autism struggle their whole lives to “fit in” and usually fail. There is no ill intent when those with Autism have dramatic outbursts derived from frustration, even if they break things (as some do). Nor do Aspies usually want to hurt real other people whose point of view they have trouble seeing. Yes, those with Autism often have antisocial thoughts, even violent ones. But they rarely act on those thoughts: partly it’s because their violent thoughts are usually directed at anonymous others or famous people they don’t know; partly they know better than to act on — or often even disclose — these weirder fantasies. Also, they are already anxious enough, and don’t need any more trouble, since, as noted, anxiety shuts down an Autistic person’s Executive Function, so those with Autism are much more likely to freeze than act out these fantasies (beyond yelling).

A Sociopath or Psychopath is unlikely to freeze during a dramatic situation, nor are they overwhelmed not knowing what to do. They know exactly what they want to do, and like with “heroes” (another interesting group of folks who take action when others don’t, but in a good way), their executive function is not blocked. Instead, their senses are elevated by fear: they get the energy to act on their negative impulses. Interestingly, I the author will freeze in the presence of anger (doesn’t need to be directed at him), and have yelling at myself meltdowns when I lose something or inanimate objects don’t “behave” as expected; yet in the face of a true emergency (like a car’s radiator overheating during a severe cold snap — -18 degrees Fahrenheit actual temperature), I’m suddenly calm and rational, and do what I must to avoid freezing to death, etc.

Reblogged this on Aspie Mouse Blog.

LikeLike