Chapter E (Therapy Dog Needs Therapy) was started in earnest in July of 2020, and completed and posted 12/31/2020. While Ch. E tackles issues such as the use of therapy animals, race, immigrant/ trans-national families, obedience, training, boundaries and self-confidence, the major themes of this chapter revolve around play, friendship and loneliness on the part of this work’s characters: rodent, human and canine characters, be they Autistic or not.

While a dog met Aspie Mouse’s forebear in a comic written when the author was about 13, this version’s plot is all-new. It’s a relatively short chapter (albeit four pages longer than previously), yet a lot happens. The questions raised won’t truly be “resolved” until Chapter G in Volume II. As for questions about splitting this graphic novel into two volumes: Why is Ch. E the last chapter of Volume I? And why is Ch. E in Volume I at all? Answers: To keep both chapters related to the Castelluzo family’s “summer house sitters” (D & E) together; and to have five “action” chapters in each Volume, after adding a new Chapter J. While the split is necessary, as the graphic novel just grew too big, the result is that related chapters end up in different volumes: for example, Ch’s. A and H (H repeats A, and adds material); and then Ch’s. B, C, D, as well as E, will have characters reappear in Ch. G. However, after Volume II comes out, a combined hardback version of Ch’s. A-J is expected, which will then reunite all chapters together.

In early 2022, Chapter Pre-A (Preface) refocused on 27 common characteristics of Autism — showing how the behaviors of Aspie Mouse and other Autistic characters in this graphic novel fit them. So these traits, emphasizing their positive sides, needed to be added to all chapters — which had already been written — starting with Ch’s. A-E in Volume I. Also I decided to add new “thought balloons,” to better show (mostly) Autistic characters’ true motivations — especially when they differ from their words — as they interact with other characters. For Ch’s. A-D, no new pages needed to be added for both tweaks, because prior revisions had already resulted in longer chapters. However, Ch. E’s panels — never having been revised since first written in 2020 — increased by 25% (four pages). Next: Ch. Pre-A (Preface) will get one last overhaul, and Volume I will be ready for formal publication. THEN work will resume on finishing the new Chapter J, after which the same “tweaks” will be added to Chapters F-I that A-E have received, so Volume II can also be published promptly.

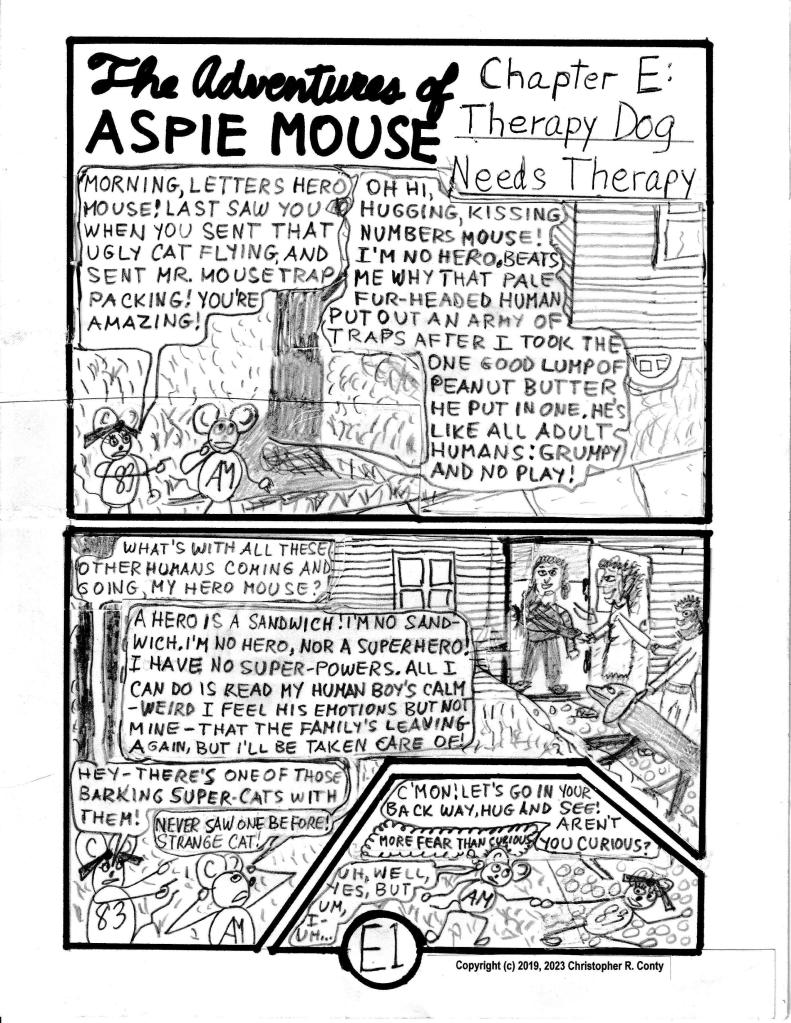

Notes for Chapter E, “Therapy Dog Needs Therapy”

Synopsis: While the central character of this graphic novel overall is a mouse with Autism, other characters — rodent, feline, human and sometimes other — have prominent roles depending on the chapter. Chapter E focuses on a human girl who also has Autism (Desiree a/k/a Deedee).

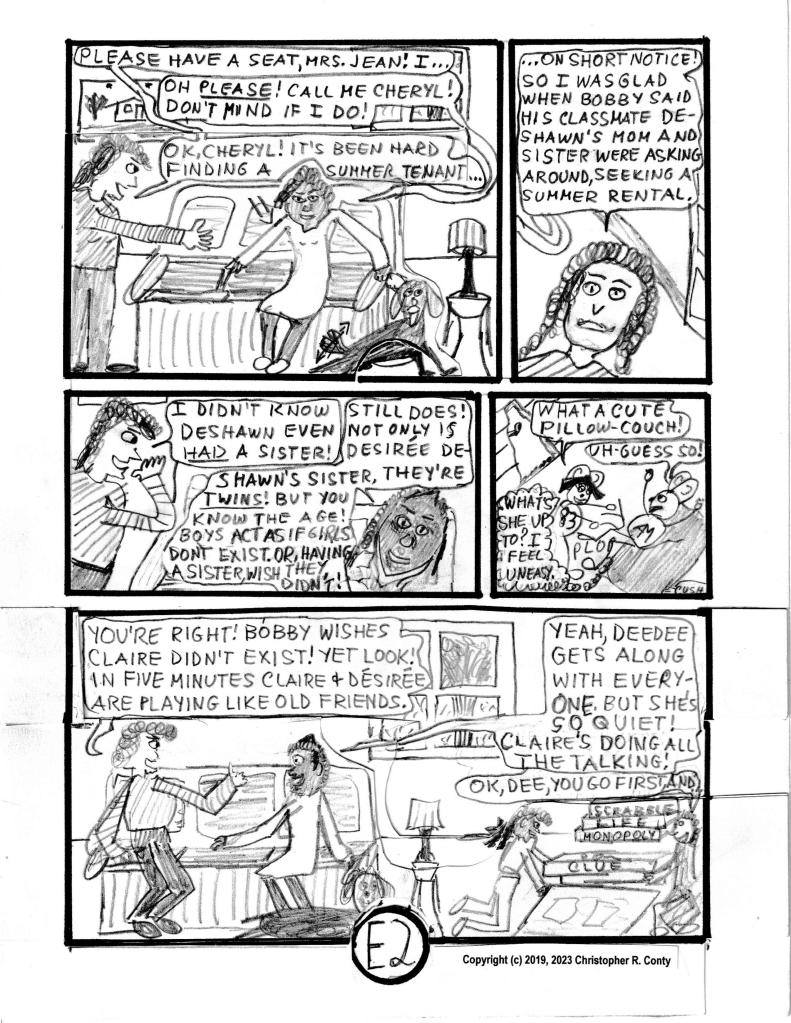

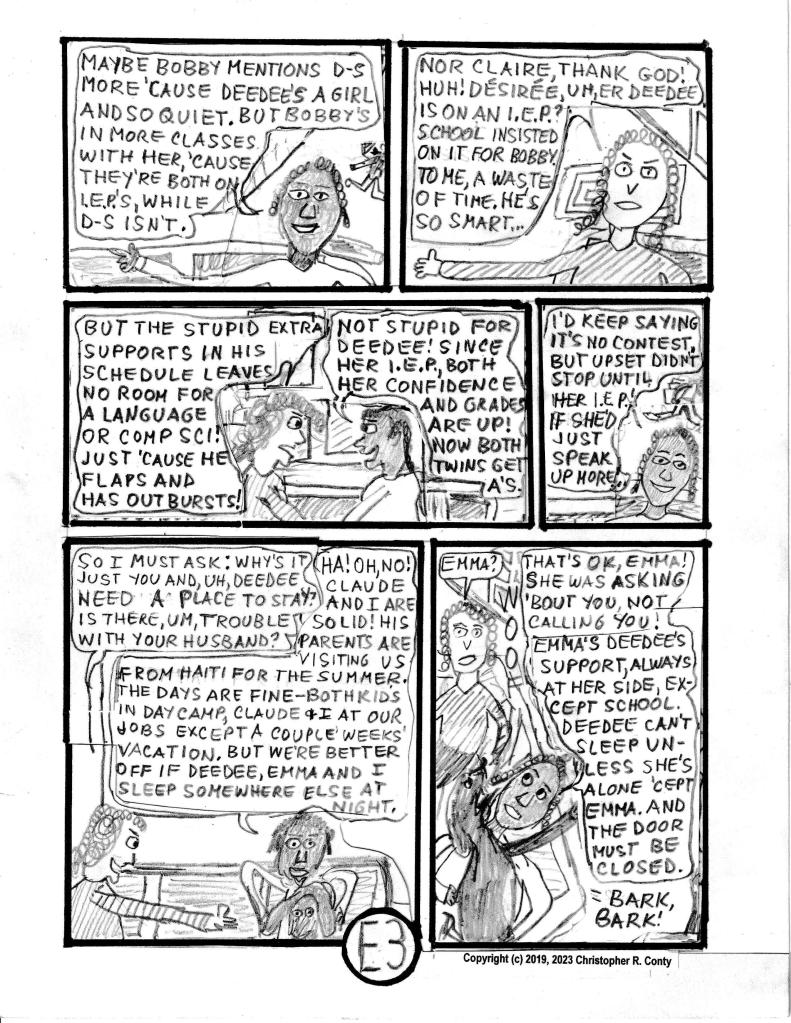

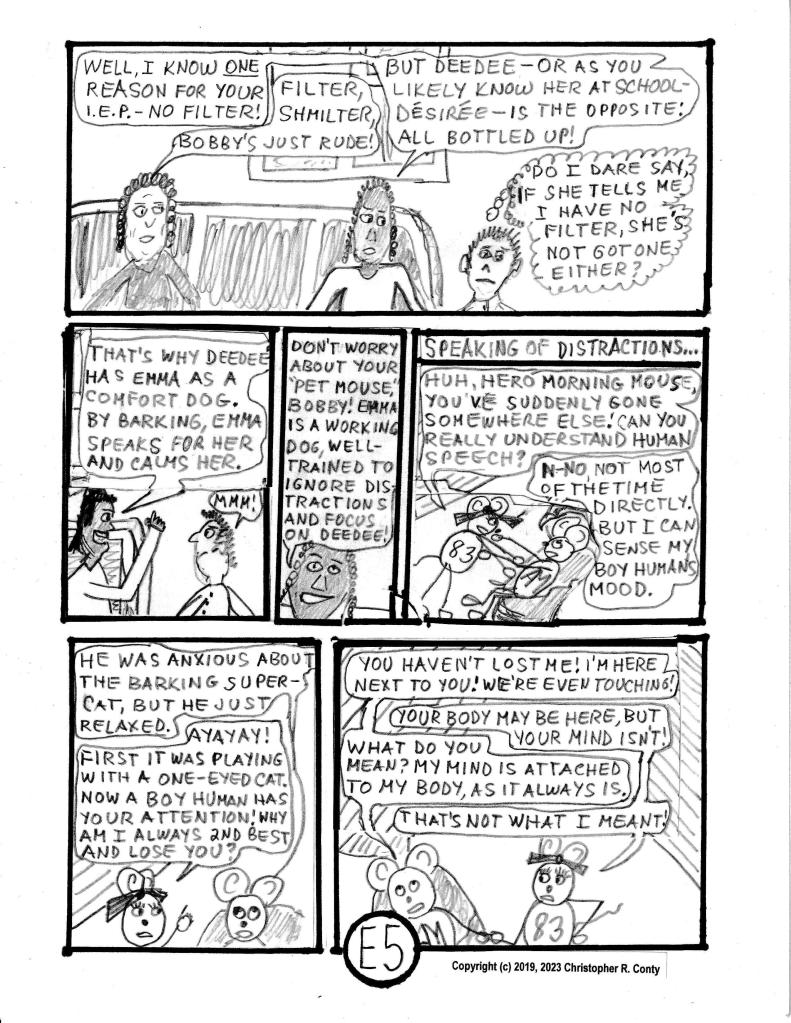

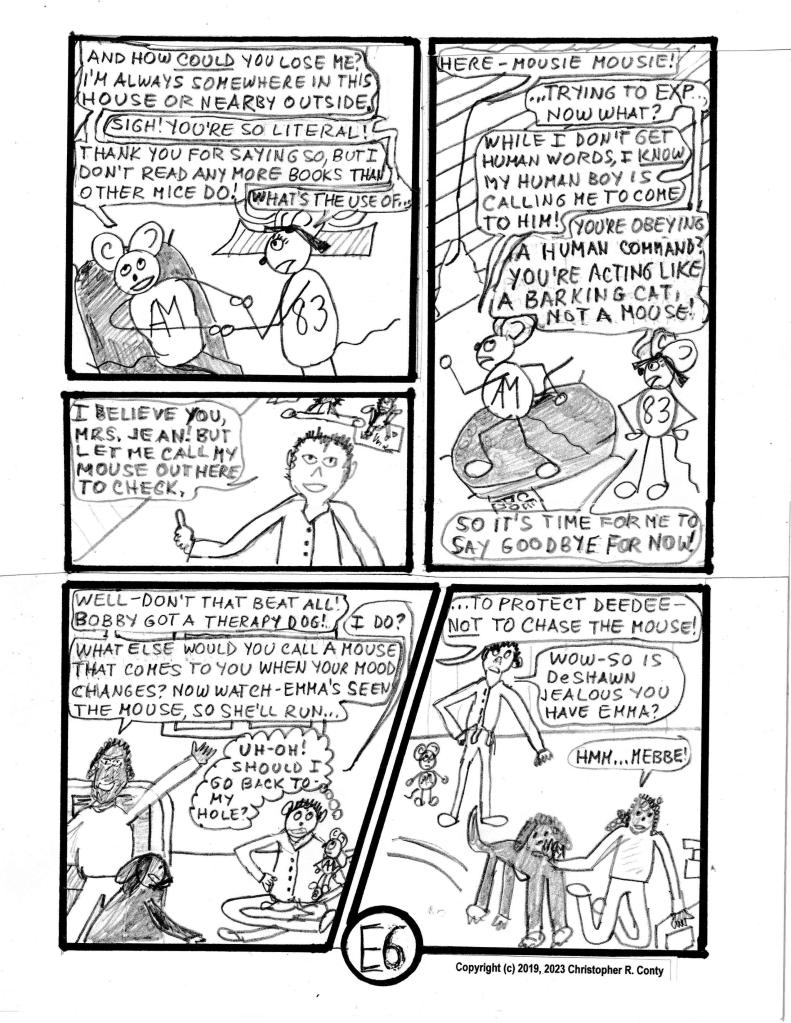

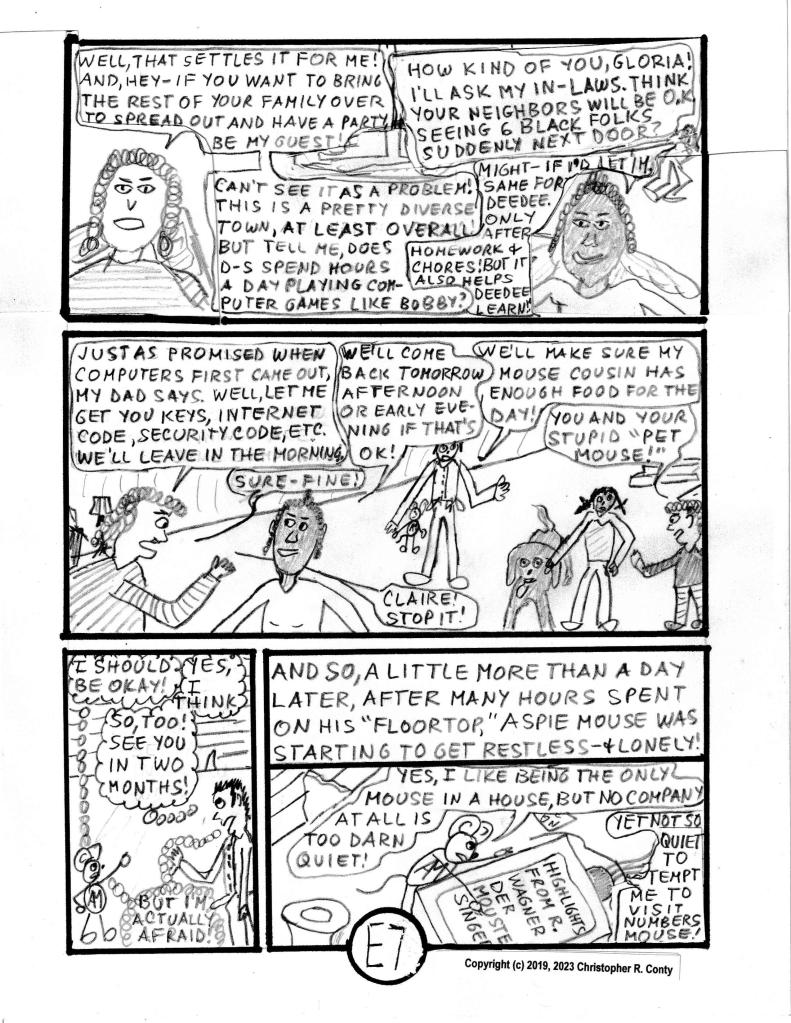

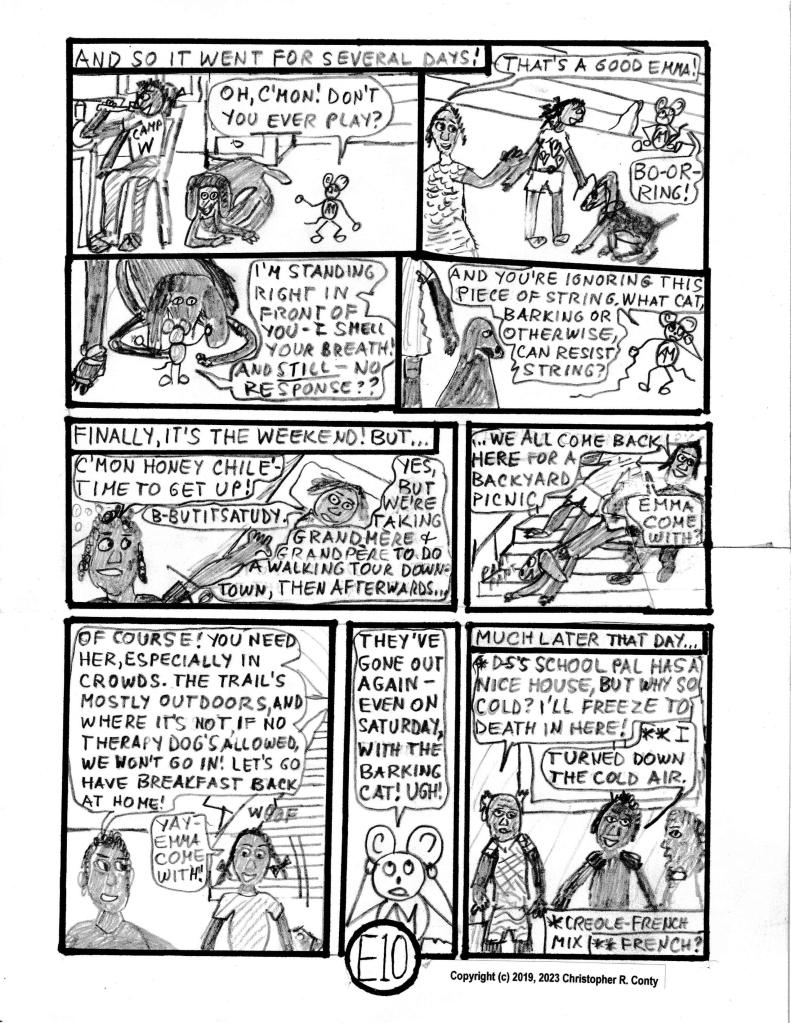

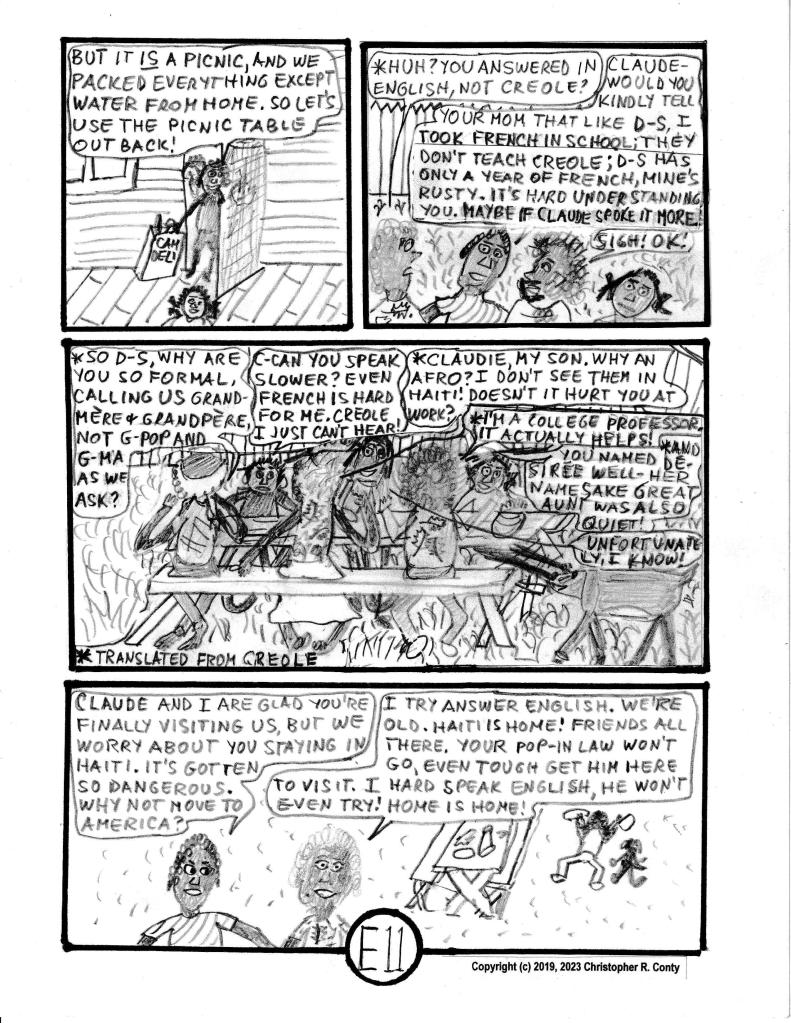

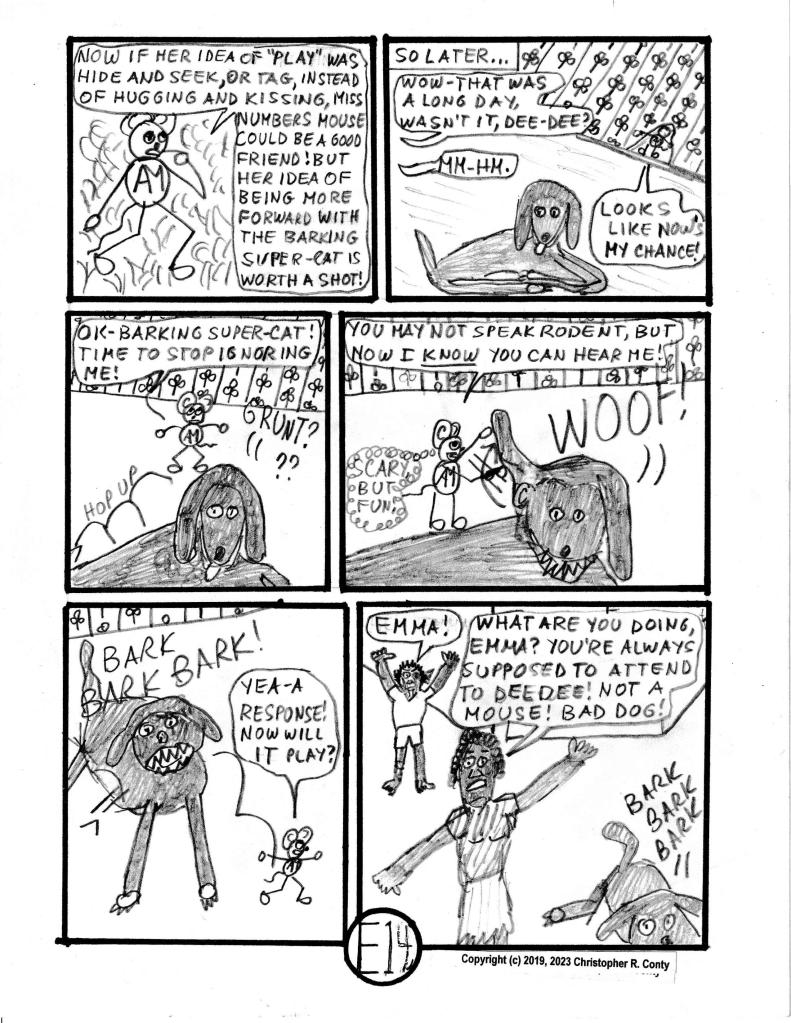

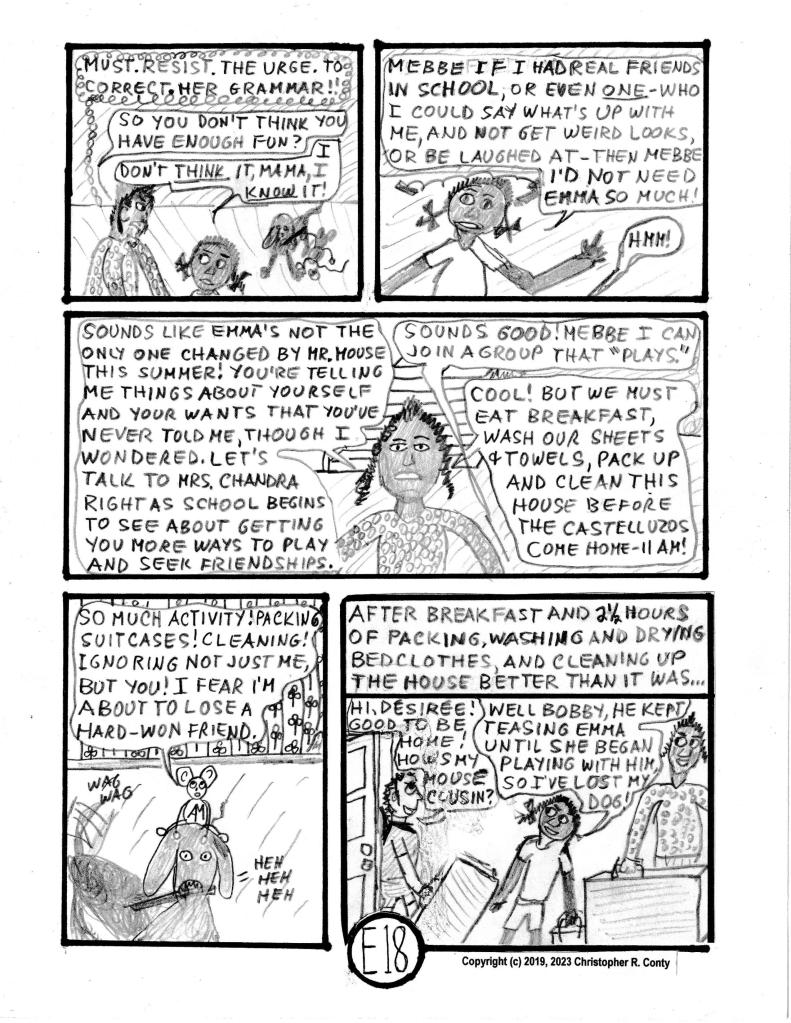

Chapter E starts as a mother (Cheryl Jean), daughter (Desiree/ Deedee Jean) and dog (Emma) arrive at the Castelluzo home to see about house sitting for the summer, after Mr. Kaputin (Ch. D) left after just a couple of days. Meanwhile, Aspie Mouse and Mouse #83 from next door speculate as to what it all means, with both so unfamiliar with dogs they call them “super (barking) cats.” As the two mothers converse, the difference between how Gloria Castelluzo treats Bobby’s Autism and how Cheryl Jean treats Deedee’s is obvious — mostly denial (Gloria C.) vs. highly engaged (Cheryl J.). Meanwhile, #83 is frustrated with how attentive Aspie Mouse is to Bobby’s moods and needs, vs. paying more attention to her.

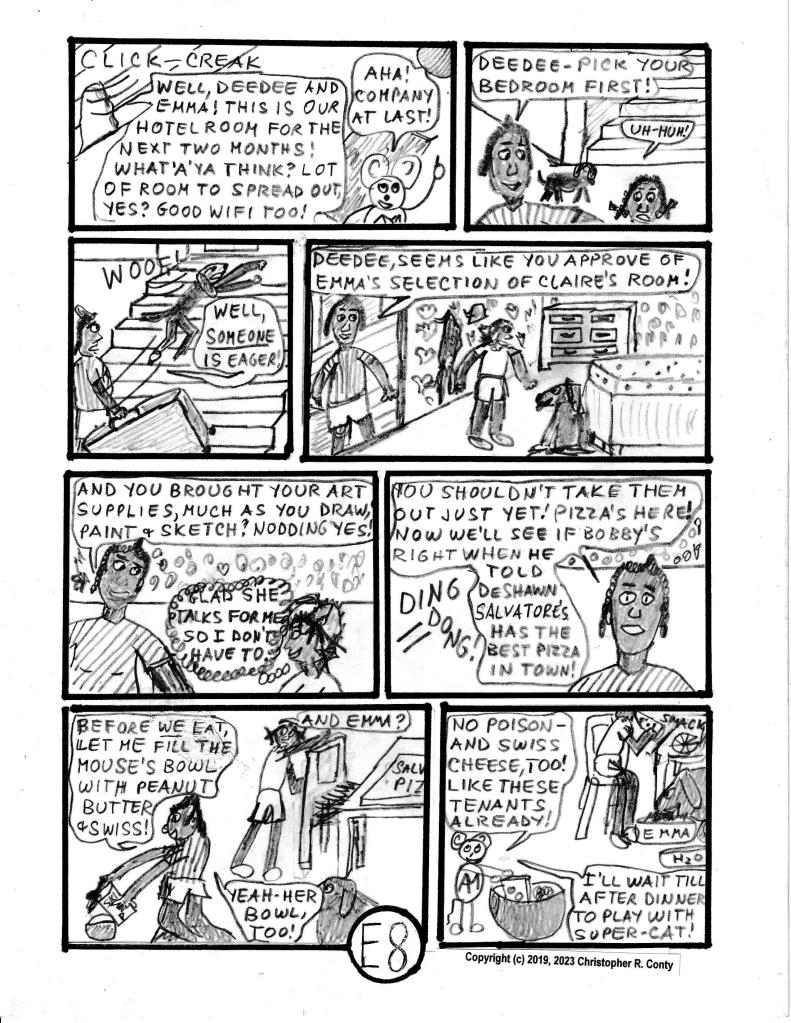

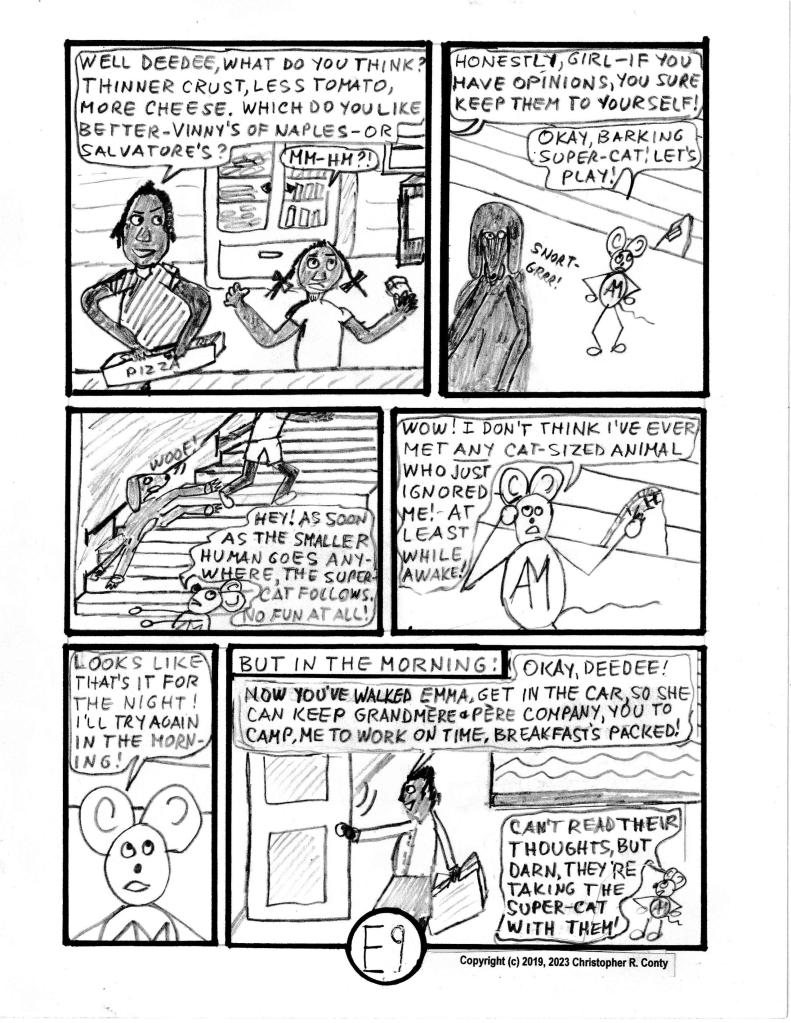

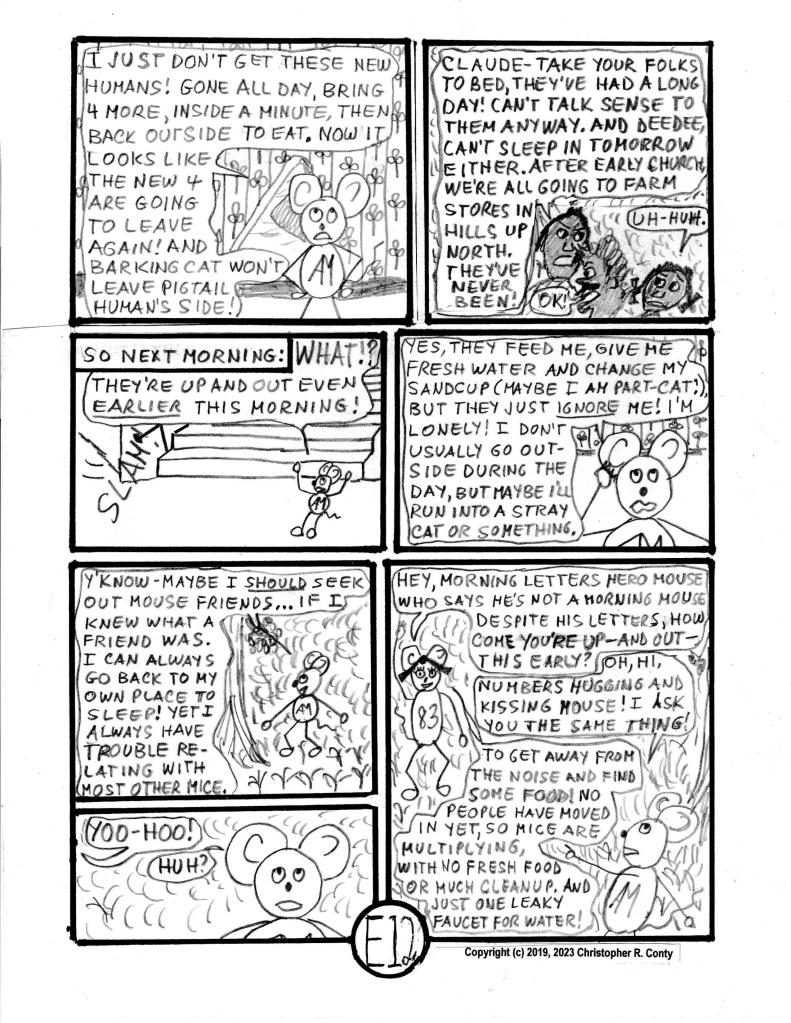

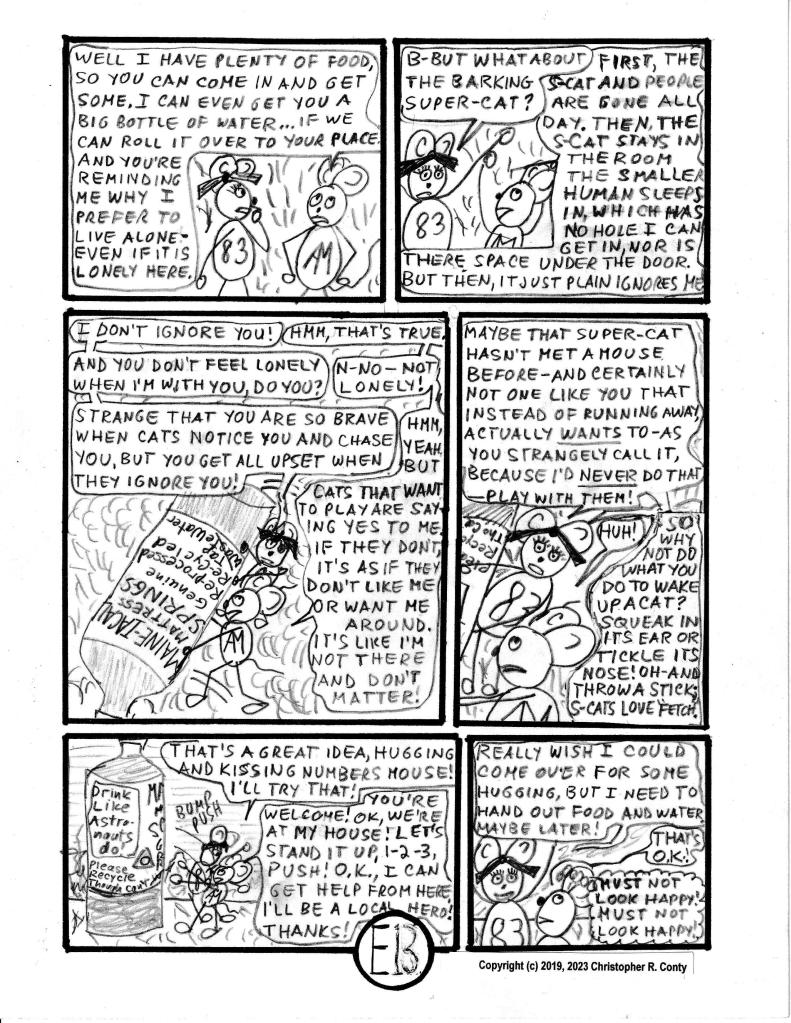

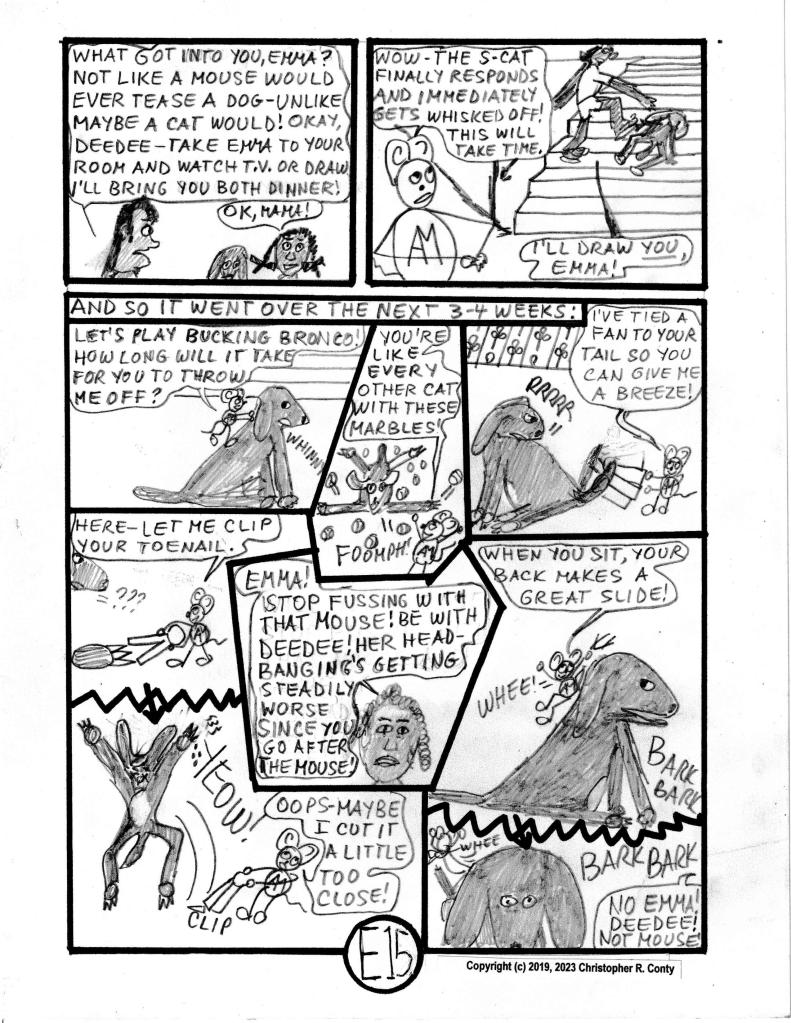

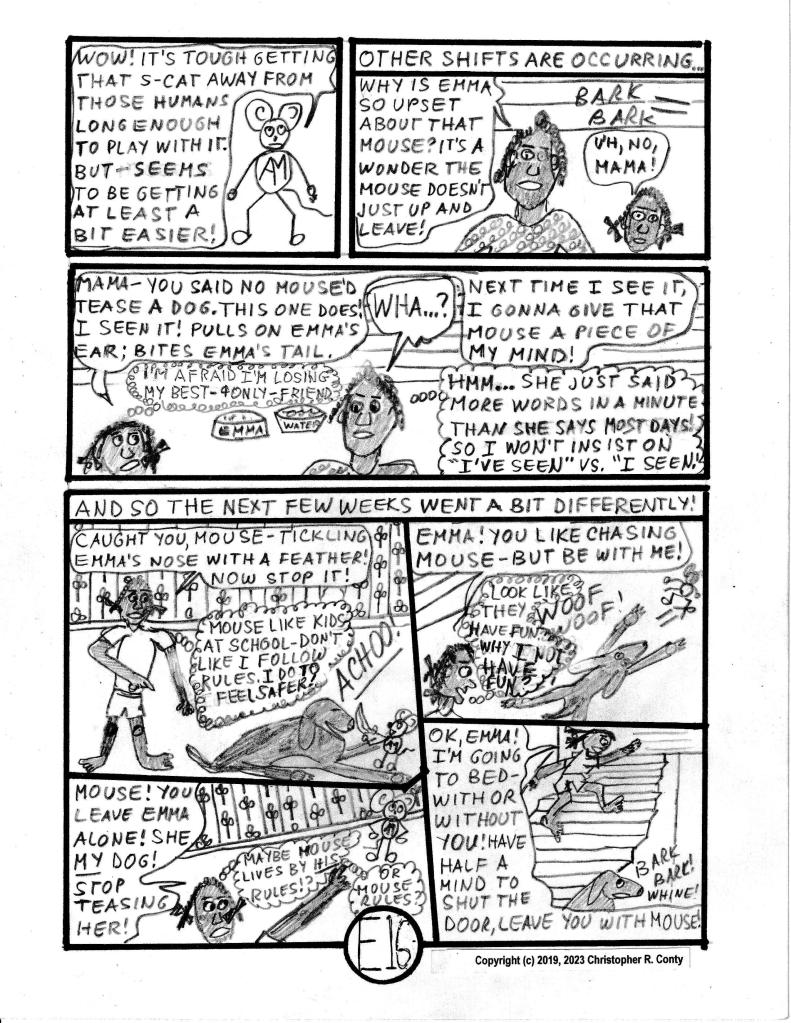

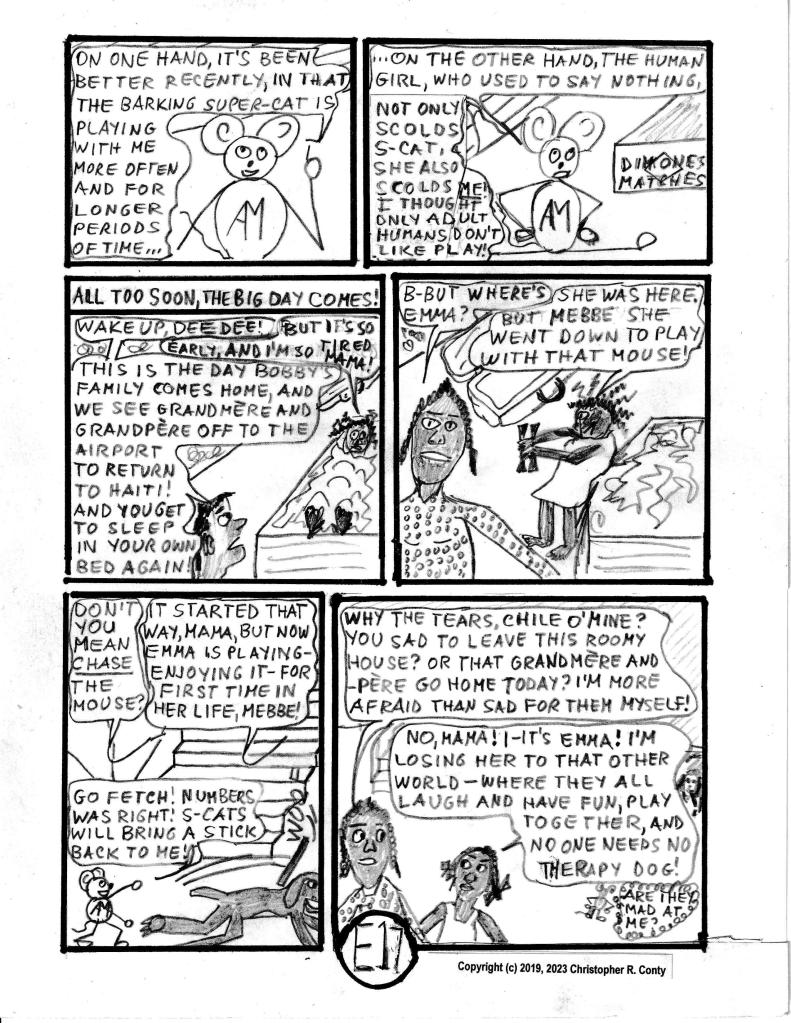

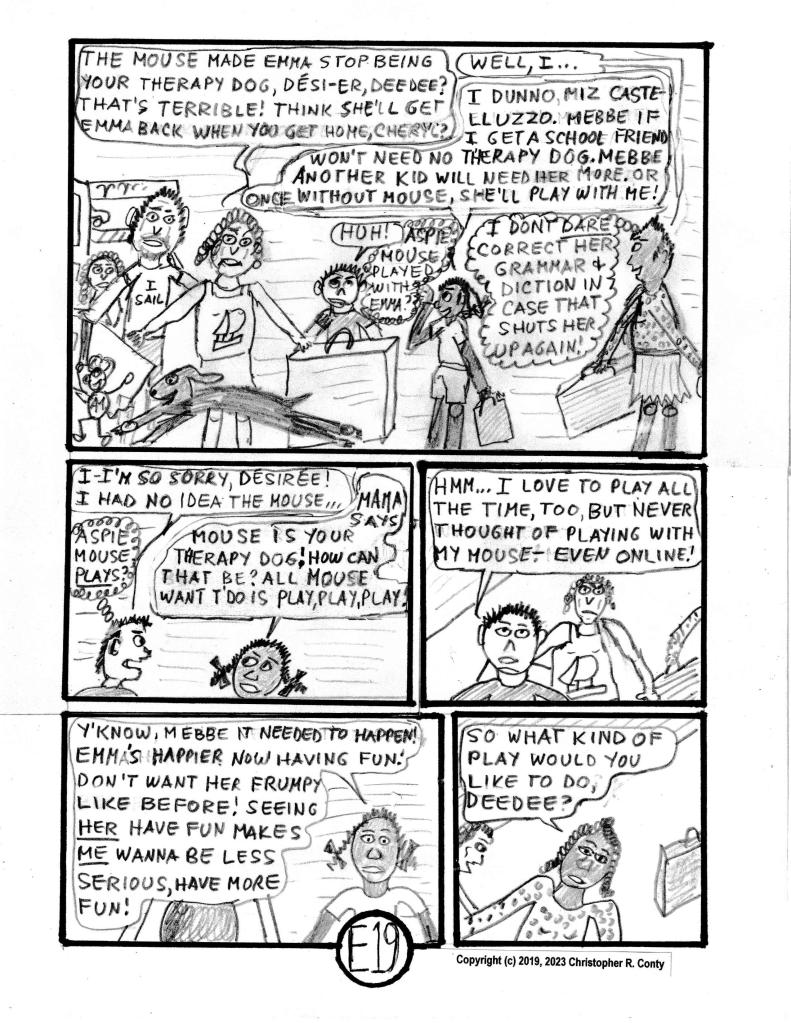

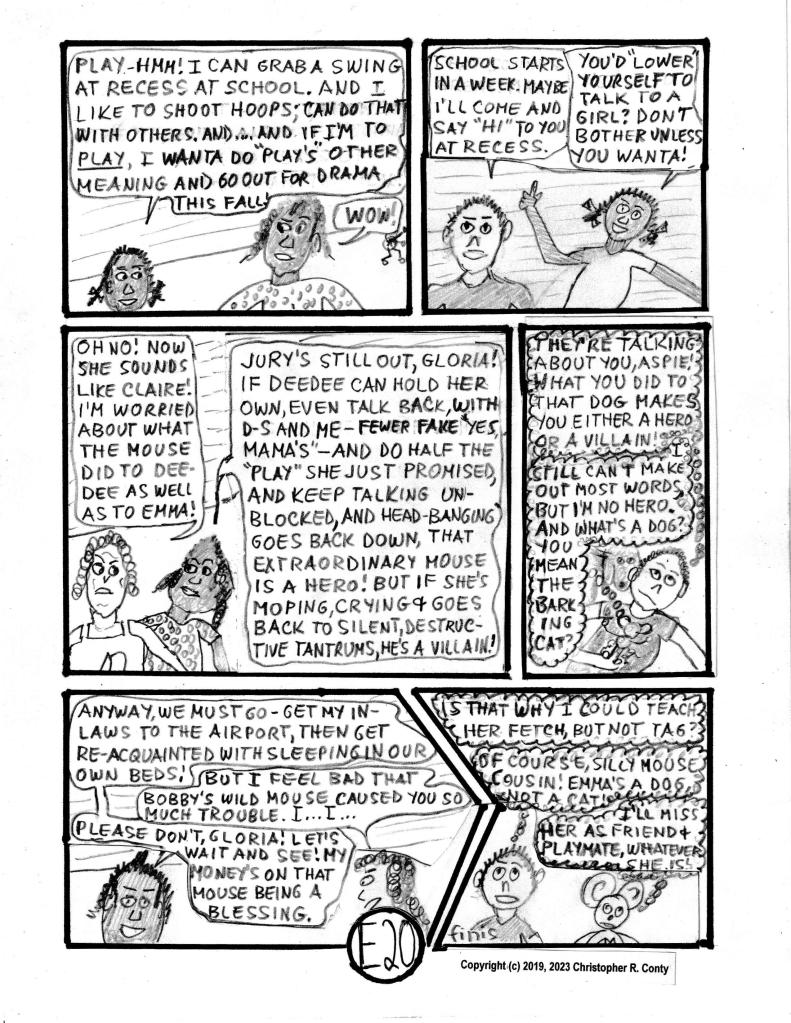

Once the Castelluzos leave and Cheryl, Deedee and Emma move in, Aspie Mouse tries, initially unsuccessfully, to get Emma, a therapy dog, to play with him, while Cheryl and Deedee do their best to keep Emma firmly attached to Deedee. After a while, however, Aspie Mouse gets the dog’s attention, and finally Emma learns that she’s been missing out on playing fetch, etc. Deedee, frustrated that her Therapy Dog is being lured away from her, changes from being very quiet to become more and more vocal in frustration. Cheryl’s initial concern about Deedee losing Emma’s undivided loyalty is diminished as she notices Deedee suddenly talking a lot more — a new behavior — and seeming more self-confident. When the Castelluzo family returns, neither Cheryl nor Deedee is sure if Emma’s behavior change — and its impact on Deedee — is a net positive or a net negative. Mrs. C is appalled to learn that “Bobby’s mouse” has caused so much trouble with Emma, but Cheryl Jean tries to calm her down by saying “the jury’s out.” This will be “resolved” in Chapter G in Volume II.

Topic-specific notes:

Theme #1: While Ch. E tackles issues such as the use of therapy animals, race, immigrant/ trans-national families, obedience, training, self-harm, boundaries and self-confidence, this chapter’s #1 theme revolves around play, friendship and loneliness on the part of this work’s characters — rodent, human and canine — Autistic or not. This theme isn’t new: it comes up in one form or another in each of the preceding chapters A-D. However, Aspie Mouse’s admission of loneliness is more pronounced than in prior chapters, and what he does to end his loneliness is unique.

Theme #2: Unique to this chapter is the use of a therapy animal (a dog, Emma) by one of the characters, an Autistic girl, Desiree (Deedee) Jean.

Theme #3: Chapter E adds a “stimming” situation that may be viewed as self-harm: the Autistic girl Desiree/ Deedee bangs her head on a pillow to go to sleep.

Theme #4: Introducing Black human characters. It’s tricky, given that race is such a sensitive topic — particularly when a White author portrays Black characters. I’m proceeding because — as I explain below — while I can truthfully also say that any resemblance to actual people, living or dead, is coincidental, the Black human characters are inspired indirectly by actual people I grew up knowing — though they have different genders, ages & circumstances. I want to honor these people I grew up knowing (see below) and have received the blessing of the one member of the inspiring family who is still alive.

Details re each of these themes:

First: play, friendship, companionship and loneliness. While friendship has been discussed in prior chapters (especially B & D), this is the first chapter where Aspie Mouse uses the word “lonely” without having “anyun” (used vs. “anyone” to include other animals besides humans) to play with. It’s the next step from Ch. D, when he says he’s a “failure,” because he has no friends. In his life so far, that’s meant no cats to play with.

Once again (as in Ch’s. C & D), he dismisses #83 (the mouse next door) as a friendship/ playmate option, because: (1) he wants to avoid any romantic or sexual complications, and (2) #83 isn’t a cat, and for whatever reason, therefore not a preferred playmate.

Loneliness can be a common issue for those with Autism. It results from difficulty in forming human attachments that last, much less true friendships. What is friendship?” also comes up in prior chapters starting with Ch. A, and continues to be important throughout both Volumes I and II. Play is also not a new topic. Aspie Mouse of course LIVES to play! In Chapter A, when play gets taken away from him, he gets very upset, blaming adults (rodent or human) as being anti-play! Being “prevented” from play comes up clearly in this Chapter E, but also Ch. F, G, H (as it repeats Ch. A material) & I in Volume II.

It’s a paradox: individuals with Autism can generally tolerate — and even prefer (as Aspie Mouse admits) — being by themselves for much longer periods of time than almost all Neurotypicals, given that human beings are by nature social creatures that usually function in groups. Of course, Autism is a condition of opposites: so while SOME with Autism may be fine living alone on a desert island, OTHERS will want to “come out of their cave” on a regular basis to find other humans to talk to — when they can’t, it can drive them a bit crazy. Even for the most reclusive Autistic adult living alone, however, there usually comes a point when the absence of any real in-person companionship (vs. Internet-only “friends) can become as big a need as food, shelter or a good night’s sleep! The pandemic certainly made that evident!

Probably half of people who are introverts, especially those with Autism — including this Author’s father and son — have a good time with one or two friends wherever they are — often after someone else has taken the initiative to get them together. But if either party moves away or one “outgrows” the other, my father (and probably my son) would make no effort to stay in touch. A new friend may then be found and the cycle repeats. My grandfather (father’s father) was even more extreme: I doubt he had any friends at all! One reason (among several) I believe that my college roommate — a Psychiatrist — may be Autistic is how he’s like my father: behaves just like that: as close as we once were, I almost never hear from him, even when I reach out.

An extrovert and only child, I (the author) am the opposite, firmly on the “needs regular social contact” end of the spectrum, having “collected” friends to play with as a child — though I always wanted 1:1, never part of a 3-or-4-some — and keep people in my life from wherever I’ve lived by sending those I knew holiday cards (well over 100 a year). I invited hundreds to my late-in-life wedding, though only a third showed (still over 100). My friends have little in common with each other; few KNEW each other. How often have I confided my deepest feelings with any of these friends? Rarely! I work best solo. I am not a team player. I couldn’t study in a group: I must be alone to study for a test or do creative work (like writing this graphic novel). I hated group projects at school! Yet I can talk on the phone for hours one-to-one, including calling strangers as customers or prospects. As I’ve observed in others with Autism, when I finally got married, the family satisfied most needs for companionship (friendships suffered), and then even the family didn’t get the attention they should have — working on this graphic novel is less anxiety-producing than spending time with my wife and kids, much as I love them!

When those with Autism do “connect” with others, they’re commonly one-dimensional relationships, such as computer game buddies. As children and teenagers (unlike me), they rarely follow up on their own to expand these “buddies” into friends outside of the one arena where they found each other. It often requires adult intervention to prompt more (or any) in-person activities.

This is where Chapter E differs from prior chapters: it differentiates having a “playmate” from having a true “friend.” A true friend is hard for anyone to get, but it’s especially hard for one (or “un”) with ASD. Chapter F (first chapter in Volume II) will make this distinction even clearer. In Neurotypical eyes, Autistic companions or playmates would more likely be seen as acquaintances — even if their time together can feel intense — rather than true friends, because they rarely involve actively listening to each others’ life concerns. Chapter F (first chapter in Volume II) will make this distinction (playmate vs. true friend) even clearer.

There are Autistic folks who never reach out, even as adults, nor do they have anyone reach out on their behalf, who can be super-lonely. It’s implied in this chapter that Desiree/ Deedee seems to lack even this looser Autistic definition of a human friend (playmate, companion).

How this “plays out” in this chapter: After his human family leaves for their summer place again, Aspie Mouse claims to be lonely, but he is picky as to whom/ what he pursues. He dismisses #83’s offer of companionship, because she wants to do things with him that make him uncomfortable. Of the three newcomers, he’d dismiss Cheryl Jean immediately as like all adult humans – interfering nuisances who don’t believe in play. As for Desiree/ Deedee — who is a child the same age as Bobby, and also Autistic — Aspie Mouse likely sees her more as a rival, given her closeness with Emma, and with such a different personality than Bobby (per Ch. Pre-A, page 2, “If you’ve met one person with Autism, you’ve met one person with Autism.”) So Aspie Mouse targets Emma, which makes sense, since he believes Emma is a “super cat” — having no prior experience with dogs — and therefore for him a preferred potential “playmate.”

By the end of the summer, Aspie Mouse succeeds in getting Emma to be his playmate — while of course ignoring the impact that has on the humans in his life. With Bobby’s return, however, it’s clear the relationship between Bobby and Aspie Mouse isn’t as playmates — Bobby admits on p. E-19 that he doesn’t really play with his “pet mouse.” Then what is it? Master and subject? Friendship? Is Aspie Mouse Bobby’s “therapy animal” as both Cheryl Jean and #83 suggest? (If so, wouldn’t Bobby insist he had to have Aspie Mouse come with the family to the Lake house?) Is Bobby a “big brother” protector for Aspie Mouse? Yes, Bobby rescues Aspie Mouse from Brilli in Ch. C. However, it cuts both ways: in Ch’s. C & D, Aspie Mouse’s actions accelerate the departure of two dangerous Antisocial Personality Disordered individuals from the Castelluzo household.

This Author suggests that the bond they’ve developed, including reading each other’s thoughts/ feelings — even without being “playmates” — is probably the closest to true friendship that either one has ever experienced. Aspie Mouse isn’t lonely when Bobby is around because Bobby sees him for who he is, cares for him, likes him, and shares having Autism with him. As a result, Aspie Mouse’s spirits get lifted — maybe as much as they do when he’s playing with cats that, uh, aren’t really playing! — yet in a different way.

Second: Therapy Animals: The use of therapy animals for people with Autism is fairly common, but often expensive, and rarely covered by insurance. They’re usually dogs, but not always. My son knew a fellow student in his Autism support group (Social Cognition and Academic Support classes per his IEP) at his Middle School and High School who had a therapy dog. This other boy couldn’t bring the dog to class, but on days when there were meetings at the school (not classes), he could; so I met the dog.

Not much to say here. There could be good classroom discussions about the use of therapy animals, including where they’re allowed and when they’re not. Question Set E-4 asks about pets in general and therapy animals in particular. This is the first Question Set devoted to either pets or therapy animals in these Adventures.

I don’t know if imaginary friends, apparently common in childhood (in my status as an only child, I made them brothers — maybe we were identical quintuplets?), are especially intense or last longer for children with Autism, but it wouldn’t surprise me. Part of their appeal: I can control the behavior of an imaginary sibling or friend, unlike a real sibling or friend.

Third: Self-harm (Head-banging) as “Stimming”: Desiree/ Deedee is revealed to bang her head on her pillow — she says it helps her go to sleep — a “stimming” practice that can also be viewed as a “self harm” issue. Children and adolescents with Autism often engage in such possibly “self-destructive” behaviors (cutting oneself, a more dangerous act, will be mentioned in Chapter J), including banging one’s head against a wall, rocking back and forth, etc. Kids are also prone to do behaviors such as spinning (see Ch. D), flapping (several chapters), rub their faces, rub their hands, use a fidget, etc. Why head-banging? It’s what I, the Author used to do — drove my Scoutmaster crazy when my Boy Scout troop would rent a cabin for winter camping weekends. The guess here is “restless leg syndrome” might come from a similar compulsion — the need to self-comfort.

Fourth: a long (maybe over-long?) discussion of race, immigration and the names used for humans in this chapter. Because Desiree’s family is Black, issues of race, racial inequality and immigration in American society are touched upon — though not in depth. Race is incidental to the story line. And yet…

Given how sensitive race is in the U.S. (in particular), it’s fair to wonder why I introduce a Black family in this chapter. Let me anticipate questions you may ask, followed by my answers/ reasons as to why this white male chooses the Jeans (two females in particular) for this chapter/ situation.

- Should the Author have introduced the race component in this chapter, vs. making the new family’s ethnic background more ambiguous or less well-developed?

- Should this second human family introduced be less traditional (married woman and man, two kids — one of each gender), given how few real families these days match this “ideal?”

- How realistic is the situation that leads to the Jeans being the next sitters (Bobby & DeShawn are friends at school), given the scarcity of real mixed-race friendships and neighborhoods in the U.S. in general (except on TV, the movies and in advertisements)?

- Should a white author ever dare develop Black characters in any depth?

- Is it realistic to portray a “middle class” Haitian family flying to the U.S. for a vacation (whoever paid the airfare), given all the barriers for visitors from certain countries — Haiti in particular — and that country’s widespread poverty and violent history?

- Should I use “Black dialect” for any of the Jeans’ speech — especially Deedee’s?

Here are my answers as the author, not necessarily point-by-point: I believe the race and family origins of the Jean family — both parents being Black: one (Claude) emigrating from Haiti, the other (Cheryl) descended from U.S. enslaved people — enhances the story line of this chapter. More to the point, it’s my way to pay homage to the Black family in Apartment 11H, two floors up from my own Apartment 9B (in the so-called “middle income housing project” we lived in) — whose two brothers I grew up playing with, especially the younger brother Keith — who remains a good friend to this day.

Note that I dedicate this Volume to these brothers — due to my gratitude for all the 4-page comics with suspense continuations we’d put under each others’ doors, along with my special admiration for the older brother Karl’s artistic/ comic-creating talent. I wanted to do more. So, as with the Jeans, one of Keith and Karl’s parents was of Caribbean West Indies origins (U.S. Virgin Islands, not Haiti) and the other was descended from Southern U.S. enslaved people — but as the parents’ genders were the reverse of the Jeans, Keith’s family kept his long slave master name, Witherspoon.

In 6th Grade, when asked to write an essay as to who I’d like to be if I could be anyone else, I chose Keith! As an only child, I envied the way he and his older brother played out the stories they created in their comics in their shared bedroom. Also, they had toys with batteries, while my dad insisted I use my imagination instead. And their Christmas tree lights had those moving bubbles, whereas our tree just had non-blinking lights (though we had better ornaments). I’ve remained loyal to my dad by being a non-blinking-light Christmas tree devotee to this day, but if I ever see bubble lights for sale, I might be persuaded to buy a set!

I want Karl remembered decades after his too-short life ended so tragically and abruptly. Karl died of a drug overdose in his early 20’s. His loss remains a hole in my heart; the impact on Karl’s parents, brother and sister were of course much greater and forever. He was so smart he skipped 3rd Grade! Keith, like me, didn’t skip, but he was, also like me, in the “1” class for high scoring students, as the City of New York believed (and still believes!) in “tracking” by ability for Grades 2-6. Sad commentary: Keith was the only Black kid in my grade or his (one year younger) to be in the “1” class, though the school and neighborhood was probably 15% Black. In my arrogance during that time, I wondered if our friendship had anything to do with Keith being in the “1” class — I can say now, no, he was always that smart. I learned about Karl’s death too late to attend his funeral — from a letter my mother sent me during my Junior Year in college. I’d have skipped classes (which I never did) and gone home to attend that funeral had I known! Such a tragedy and a waste: his family and the world were deprived of Karl’s strong Black pride voice and his immense artistic talents.

Next, why did I pick Haiti for Claude (Cheryl’s husband) Jean’s origins? Partly to offer some history lessons. In this chapter, Cheryl Jean explains to Bobby that she took her husband’s Haitian last name to get rid of her own “slave master” maiden name! The author personally knows Haitians, and first names seem even more popular there as last names than in U.S. white culture (as to why, I’ve speculated!). As for the first names in the Jean family, the adults have traditional “English” names because that’s what so many Black families I knew way back when used: my friend Keith, his brother Karl, their sister Kim(berly); their parents were Maurice and Venia. The kids in this current generation, though, have been given more “Black” or “French” names (DeShawn and Desiree).

Historically, Haiti was second only to the U.S. in the Western Hemisphere in declaring its independence from Europe, but unlike in the U.S., Haiti was freed by a slave rebellion. I acknowledge that Haiti has come upon hard times — the poorest and in many ways most chaotic country in the Western Hemisphere. I want to show that even amidst all that, love of homeland remains strong, and to praise the positive contributions immigrants from all countries make to our society. One example: as with immigrants from the Philippines, Haitians are strongly represented in health care settings; they’re healers. Oh, and by the way, Keith made several visits to Haiti earlier in his adult life — which then prevented him from donating blood!

As for why none of the Jeans speaks using “Black dialect ” — especially Deedee when she finally starts speaking in longer sentences — I am again writing what I know! My friend Keith says he was strongly encouraged by his mother from the Virgin Islands to speak “proper English.” Some Black friends hassled him over the years for speaking “white,” but he honored his mother’s wishes. I get it! It’s like my own speech: I grew up in the Bronx, but speak with a non-regional accent, first because I mimicked my midwestern parents, and second because my father was a social striver who wanted me to sound like a rich WASP — White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (“If you’re going to sound like a New Yorker, sound like you live between Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue, and between 59th Street and 72nd Street!” vs. the New York-ese spoken by most of my peers (my father again: “If I hear you holding onto your G’s and D’s and T’s — e.g., Lun guy lundd — I’ll “brain” you!”). Yes, I have a good ear for sound, but having Autism means I wasn’t so peer-influenced. So like Keith’s mother, Cheryl is able to make sure when Deedee speaks, she speaks the way Cheryl does, using “proper English.” Deedee’s father, a Haitian immigrant, wouldn’t likely speak “American Black Dialect” either. As for Deedee’s twin DeShawn’s speech, we’ll get more of it to judge in Chapter G.

I admit I almost did have Deedee use Black Dialect as a way to “rebel” against her mother, after all those years of just saying, “Yes, Mama.” It would have given Cheryl another reason to resist the urge to correct Deedee’s speech. As Deedee starts talking more, Cheryl’s desire for her daughter to speak non-dialect English to get ahead in a white society is tempered by her fear that Deedee will shut up again if she does. So for now, she lets Deedee’s grammar lapses go — to be expected, given how seldom she’s spoken at length. For all we know, Deedee could be grammatically correct (in the eyes of educated white people, anyway) when writing, given how people write is often different from how they speak. It’s a tough line I’m trying to walk. In my experience, when Black Dialect is put down on paper or via keystrokes — where inflection, tone and emphasized syllables disappear — what remains are grammatical differences: “was” instead of “were”; “we done” instead of “we did/ we’ve done,” etc.

I don’t see Deedee as “rebelling,” so much as being more authentic. Why I really changed my mind in favor of what Keith and I both did — speak without a defined accent — was the 2023 movie “American Fiction” and the book it’s based on. A Black Author couldn’t get a contract by (white) publishers for writing what he knew, because it wasn’t “Black enough.” He finally gets published when he writes an over-the-top satire of Black culture by including every Black stereotype he could think of — Black Dialect, cursing, drug dealers, one-parent families, welfare mothers, etc. It’s not far-fetched, given how overwhelmingly white the book publishers I worked for were during my own textbook publishing career. Again, I am writing what I know!

In these Adventures, I try to strike a balance: I have people — as well as animals (especially mice) — of different ethnicities (indicated by names), races, religions and abilities throughout this work, as previously discussed in the notes for Ch’s A, C & D. On the one hand, I put them in situations that could be played by characters with other backgrounds by changing a few details. On the other hand, those details allow me to celebrate elements of diversity that I grew up taking for granted — only to learn later that most Americans in my generation grew up in more homogeneous (monolithic) neighborhoods. If anything, I’m only sorry not to have enough prominent human characters to also have some be of Jewish, Irish, Swedish, German, Greek, South Asian or Chinese heritage. These are backgrounds of many people I knew growing up and later — including me (Swedish & Irish as well as Italian, or as my Irish grandmother put it, “You’re a regular League of Nations!”).

I may add people of other ethnicities in Chapter J, depending how that chapter develops. Also, I’m considering having a non-traditional element be part of any new human character I introduce (including the MIT Professor in Chapters A & H, though she’s already an Hispanic woman as an Institute Professor — not sure either her gender or ethnicity is so represented in reality) — be it sexual orientation, genders of the parents, mixed race couples, etc. It’s not about forcing anything on anyone : it’s the reality of people I know! I purposely made the Jeans a “typical” family, partly to avoid racial stereotyping, but mostly because Keith and Karl’s family was indeed a two-parent family — with one anomaly vs. my other friends, who all had exactly one sibling: they had a third kid, a younger sister; I too was different, being an only child. While my current family situation may seem “typical”: I’m in a traditional marriage as part of a heterosexual couple with one boy and one girl as children (I use “typical,” avoiding “normal” — which 12-step groups say should be used “only as a cycle on a washing machine.”). Yet we’re atypical in some ways: I’m much older than most first-time dads, I have Autism and ADHD, as does my son. My other child is part of their high school’s LGBTQ+ community. My long-standing friends include two white men married to Black women. I used to work with an ex-Evangelical Christian Minister who changed careers when he came out as gay. I take more liberties on these issues with animals, because like Jonathan Swift, social commentary using imaginary creatures is less threatening to the “authorities” than using real people.

Finally, why did I make Deedee female? I didn’t realize — until I’d already plotted out this chapter and started putting it in panels — that Desiree (or Deedee) has my own mother Elsie’s personality. Born of two Swedish immigrants, my mother loved to draw as a child — she wanted to go to art school, but the Great Depression and a discouraging father intervened. She continued being artistic throughout her life, primarily with textiles/ fabrics. My mother — like Deedee — was painfully shy (even as an adult), saying very little, and in retrospect clearly had ADD (without the H, or per the DSM V: ADHD, Inattentive Type) and Asperger’s-level Autism. I’ll dedicate the Volume II of the Adventures of Aspie Mouse to my mom, Elsie, as she deserves more credit for her positive influence on me than I admitted during her pre-dementia lifetime. I wish I’d known more about Autism, as she spent so many years as a “personal growth junkie,” trying to figure out what she was dealing with. She was erroneously diagnosed with “Schizophrenia” later in life — the label high-functioning Autistics got before Hans Asperger’s work (if not his name these days) was more widely accepted. While she only rarely spoke up for herself during her lifetime, Elsie consistently picked confident, assertive, verbal female friends who loved her and cherished her talents. When she did speak up, Elsie’s words could cut like a knife, especially in defense of me. Elsie, meet Deedee. Deedee, meet my mom — in this mirror.

Notes specific to the plot and panels of Chapter E and the Questions that follow:

With the introduction of Cheryl Jean, daughter Desiree (Deedee) and Deedee’s therapy dog Emma, there are three new characters to observe, especially Deedee, who’s identified as Autistic. Deedee is initially quieter than other Autistic characters introduced so far, human or rodent — or at least she is until Aspie Mouse starts prying Emma away from Deedee to “play” with him. The other four members of the Jean family (2 grandparents, Deedee’s twin brother and her dad) aren’t around long enough for the usual Question 1 inquiry — which of 27 Autistic traits might they show?

On page E-1, Aspie Mouse denies he’s a hero or a super-hero. This came up before in Ch. D, and will come up again. Question Set E-2 asks whether Aspie Mouse intentionally NOT having any super-powers (see preface, foreword, etc.) — so he relates better to anyone (any-un) with Autism — makes Autistic readers (often drawn to super-hero graphic novels) less excited about reading this work. “Autism is my super power” is a widely used phrase that may have been first used by Jared Wynder as a 15-year-old during a TED talk, and a subsequent book. Others have come out more recently with books with this title, along with T-shirts, etc., so it’s likely not trade-marked! A teacher or parent may want to bring this issue up before Chapter E, but the Question Set E-2, about “Autism as my Super Power,” resides in Ch. E in Volume I of the Adventures of Aspie Mouse.

Because members of the new family introduced are Black, and the Castelluzo’s are White, race among people is introduced for the first time in this graphic novel, as per Question Set E-3. After being thorough in discussing race in the previous section of these notes, no need for further comment. Feedback is however encouraged, as to how I (the Author) might handle things more delicately — or elegantly. Race among animals is covered in Ch’s. B & H.

Question set #E-4 is about Therapy Animals — and how having one may help lower anxiety. Anxiety is such a major issue for those with Autism that it’s addressed in every chapter and in most chapters’ Question Sets. Is Aspie Mouse Bobby’s Therapy Animal, as both Cheryl Jean and #83 suggest? Or are they playmates? Companions? Friends? (See below, re Q sets 5 & 6, and earlier in these notes, re Topic #1).

Question sets #E-5 & 6 go into how “opposite” two kids can be as to how Autism is expressed, and asks readers with Autism to identify with one “camp” or another in terms of trait clusters, with special attention to the issue of saying too much, asking too many questions, and wanting to be the center of attention — all with “no filter,” as Cheryl Jean suggests about Bobby — versus saying almost nothing to avoid trouble/ call attention to themselves, and try to disappear, more like Deedee at the beginning of Ch. E. Both sets of behaviors may be hard-wired. On the other hand, in some homes one or the other may be more rewarded or more punished. A behavior that helps one “survive” at home may not be as welcomed by the outside world (school, work, etc.). You may want to discuss the consequences of “having no filters” on the one hand, and “not speaking up even when it’s important” on the other. “No filters” is what’s gotten this Author in trouble his whole life.

On pages E-4 & 5, the two mothers express opposite attitudes toward the value of Individualized Education Plans for their offspring. Just because Gloria Castelluzo is resistant to the benefits of Bobby being on an I.E.P. doesn’t mean she’s an uncaring mother. On the contrary, as subsequent chapters in Volume II will show, Gloria C is fierce in defending what she thinks are the health needs of both her kids — especially in response to Claire’s apparent allergy — even though she jumps to conclusions on the basis of questionable evidence.

Question set #7 addresses Deedee’s head-banging and whether or not the reader has a similar physical compulsion (more potentially harmful to oneself than spinning, flapping or fidgeting as noted in previous chapters and their questions) or if not, knows someone who does. As expressed in earlier notes for this chapter, the Author used to bang his head on a pillow at night.

Question sets #8 & 9 address loneliness, friendship, and other relationships — also covered in the general notes above. Similar questions occur in prior chapters, especially Chapter D’s Question set #9. They will come up again in chapters of Volume II. Question set #8 focuses on friendship as the antidote to loneliness, and then how true friendship may differ from frequent companionship. That may matter to some folks with Autism and not matter that much to others. Assuming you don’t want to assign the same question twice, check the five prior chapters for duplicate “friendship” question sets. Question set #9 continues the friendship/ companionship/ loneliness/ other relationships, focusing more on romantic love and being close physically — which Aspie Mouse finds very uncomfortable when #83 tries it with him.

Question set #10 is about Grandparents and other relatives besides parents (Aunts, Uncles, etc.). When these other relatives don’t have day-to-day responsibility for a child, teen or young adult’s welfare, their relationship may be freer from friction than with parents. And, as is shown in this chapter, the relationship may be more frustrating in certain ways — especially for the offspring or in-law of a grandparent, as we see unfold between Cheryl Jean and her in-laws.

The major “changes” in the chapter occur when Aspie Mouse is finally successful in getting Emma to first notice him, then get angry with him (Cheryl and Deedee get angry with him even sooner), and finally play with him. That gets Deedee saying a lot more words, which causes Cheryl both joy (to hear Deedee finally speak up about something) and anxiety (will Deedee lose Emma after all the effort it took to get her the Therapy Dog; and do I correct her grammar and risk shutting her up again?). Question Set #11 covers these issues.

When the Castelluzo family returns just before Desiree’s grandparents are to fly back to Haiti, everyone notices that Emma’s is less of a Therapy Dog, and that Desiree (Deedee) is no longer so quiet. The response by both the Jeans and the Castelluzos is decidedly mixed, with Gloria C. seemingly more worried about what “Bobby’s mouse” did to Emma than Cheryl J. seems to be. Question Set E-12 discusses losses of people, from death, departures, etc. First Deedee “loses” Emma; then Aspie Mouse “loses” Emma. Deedee’s grandparents go back home to Haiti. Etc.

Question for Readers: Does Deedee become assertive too quickly — not sure she needs Emma to be her therapy dog any more — even suggesting she might go out for drama in the new school year? Note that many famous actors are introverts (quiet in real life) who only speak confidently on stage while playing a role. But one may ask if Ch. E has too much of a Hollywood-style ending — given that my mother Elsie (Deedee’s “model”) stayed mostly quiet to the end of her life?** Yes, Deedee’s change makes for a good story and good material for a class or parent-child discussion.

The questions that hang in the air at the end of this chapter: Will Desiree/ Deedee continue to have Emma? Does she no longer “need” Emma as a therapy dog? If so, will Emma just become a family pet or will she be “gifted” to another family needing a therapy dog, hoping they can retrain her? Answers will come in Chapter G in Volume II! Because Chapter E is the last chapter in Volume I, its ending was just revised to be less “neat” and more ambiguous — to entice readers to eagerly await Volume II!

** My mother Elsie was a bit more complex than I indicated earlier in these notes. She was an alcoholic, and when she drank, she suddenly became quite a talker and much less inhibited — which was a lot scarier to me — due to lack of control — than when she was sober. When dementia robbed her of her memory, she also became more talkative and less inhibited — without alcohol.

Questions for Thought/ Discussion: Ch. E, “Therapy Dog Needs Therapy”

27 Common Autism Characteristics, followed by possible questions related to Ch. E:

- No eye contact

- Sensory sensitivity: noise, certain lights, smells, touch/ textures, foods, hunger/ bathroom needs; physical space (stand too close/ far from others; need escape); creative, passionate re art, music, touch

- Self-Regulation: Speech: voice volume, repetition & variability; amount (see #6)

- Self-Regulation: Stimming – flapping, swaying, repetitive body/ hand movements/ head banging; use “fidgets”

- Anxiety (fear) & Overwhelm. Executive Function closes up > Meltdown: fight, flight or freeze. #1 barrier to ASD good mental health. Key: lower anxiety — yoga, meditation, count to 10, positive self-talk.

- All-or-None Thinking & Behavior: Say too much/ ask too many questions or say/ ask nothing; flat affect or too dramatic; not show or over-express feelings (see #7); avoid people or obsessed w/ some; loves/ overuses puns or humorless; substance abuser or teetotaler — extremes, no gray. Learn to sit in discomfort, seek middle.

- Difficulty identifying feelings; then not show or over-express them. Mistake not showing for not feeling & over-showing for “acting/ exaggerating.” Learn core feelings (mad, glad, sad, scared) & “not about me”

- Lack of Social Understanding, of others’ expectations (unaware). Ask for rules, put in writing and study as if taking school test. The core trait that drives the Adventures of Aspie Mouse: why his choices makes one laugh.

- Pattern-seeking/ solving problems in unique ways: why they’re inventors, good at “detail oriented” jobs; creative, intuitive.

- Special Interest(s) can pay off having unique expertise for work/ hobby. Great for self-esteem, relaxing, lowering anxiety.

- Independent thinkers/ most inventors; no/ weak peer influence/ expectations. Also a need to work independently as a colleague, not in a team structure. Needs trusting boss!

- Persistence once fully engaged; terrifying level of energy; not easily re-directed (see #16).

- Self-entertaining: If access to special interests, never bored; needs no playmate.

- Rule follower: conscientious once buys in; then helps enforce rules, offers improvements.

- Honesty, innocence, naivete: unusually truthful, will even tell on oneself. Positive side of “lack of social understanding” (see #8). Leads to trust, but seems too good to be true.

- Love routine/ dislike change and transitions: helps in self-regulation; holds on; loyal, slow to adjust, won’t jump ship.

- Unaware of impact of actions on others (adds to friction from #8): so invite feedback, don’t explain yourself.

- More logical than emotional: Makes for discomfort – Aspie of feelings; others for Aspie not expressing them.

- Emotionally delayed: emotional age 2/3-3/4 of chronological. Catch up slowly. Good to delay intimacy (honor your own clock).

- Low self-esteem: Stop self-blame! Give counter-messages: your unique strengths & you’re not at fault.

- Lack of trust, all feels unsafe: others’ trust/ safety priorities puzzling, why is my “feels right” labeled “unacceptable?” No! Unexpected! Choose your own safety priorities or those of others in household.

- Over-sensitivity > what’s said/ happens: over-reacts or no visible reaction (cares, can’t show it). Don’t take personally, let it go, Laugh about it vs. taking too seriously.

- Can’t remember names (even faces), read body language – not priority, can be by choice.

- Disconnected from body, including health, personal hygiene, need to eat/ sleep/ use bathroom, place in “space,” prone to self-injury (intentional & not).

- Extreme thoughts swirl inside mind, unrestrained by social norms; if spoken often leads to trouble, even if you’d never act upon the more scary thoughts. Challenge negative self-talk with positives and dismissal.

- Depression, suicidal thoughts, acts: anxiety & depression treated w/ same meds (body can’t tell difference); from low self-esteem, bad self-talk, sense of hopelessness. Get help, especially Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

- Hard to get & keep friends, jobs & relationships: to overcome, must work to lessen own & others’ discomfort. Listen! Show interest in others’ lives, passions & get feedback on your impact on them (see #17).

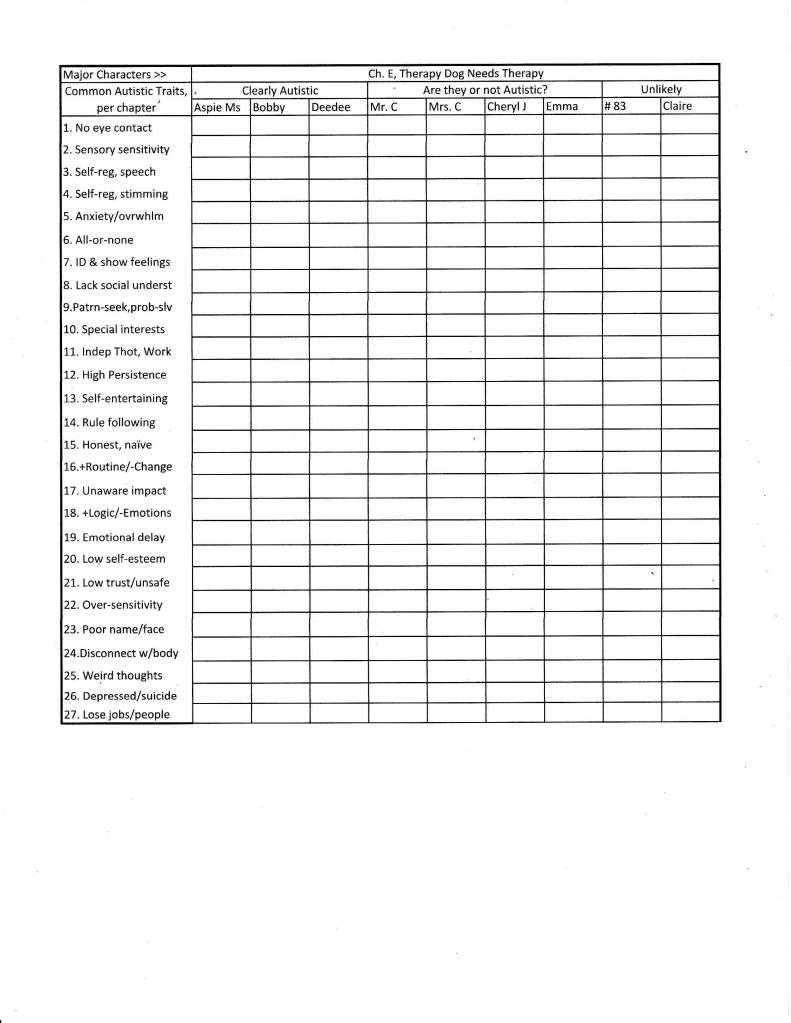

E 1: Relating the 27 Common Characteristics of Autism (above) to characters in Chapter E:

- To track the Autism characteristics that Aspie Mouse displays in each chapter of these “Adventures,” you might want to use a spreadsheet such as the one below. (Find it as a spreadsheet for Chapters A-I elsewhere on the Aspie Mouse website). Aspie Mouse is always listed as the first character for each chapter in the spreadsheet.

- More ambitious readers are invited to do the same for a new Autistic character — Deedee — and new characters not identified as Autistic — Emma the Therapy Dog and Cheryl Jean.

- Particularly devoted readers may use + and – signs to indicate when a particular Autistic trait is shown positively, negatively or some of each.

- Which Autistic trait(s) shown in this chapter do you identify with? Do you see each trait as more positive, more negative or roughly balanced? Insert a column for yourself!

- Which Autistic traits shown by characters in this chapter are not traits you have, whether you’re Autistic or not?

E 2: On page E 1, Aspie Mouse twice protests to his next-door neighbor mouse, #83, that he’s not a hero, nor a super-hero. He’s denied this before (Ch.’s C, D).

- What makes someone (or some-un as non-humans refer to other animals in this graphic novel) a hero? Is it a title that one claims, or a title others give — whether accepted or not?

- What makes someone (or some-un) a super-hero rather than a hero? Is it possessing unique obvious traits (super strength, super smarts, ability to fly, invisibility, etc.) that others don’t have? Something else?

- In your opinion, is Aspie Mouse a hero? Why or why not? Is he a super-hero? Why or why not?

- What strengths/ traits make Aspie Mouse a good candidate for being a hero? On the other hand, what challenges does Aspie Mouse face that make him not such a good hero?

- Are you particularly interested in super-heroes — as many with Autism are — and wish Aspie Mouse was one? If Aspie Mouse is not a super-hero, are you less interested in reading his adventures? If Aspie Mouse is not a super-hero, is he a better model for overcoming your own struggles? Or would he be a better model for you if he were a super-hero?

- “Autism is my super-power” is a concept widely claimed by many. How do you positively see your Autism as a super-power? In what ways is having Autism giving you (if you have it) an advantage over those who aren’t Autistic? What, if anything, makes you doubt that Autism is a super-power — in general and for you?

E 3: Bobby and Desiree’s brother DeShawn seem to be good friends — at least in school. Yet a recent study found that while 40% of the U.S. population in 2020 was other than non-Hispanic white, only 25% of white adults in the U.S. had someone who is of another race or mixed race as a member of their inner circle — close friend or relative that they regularly see, share meals with, etc.

- What reasons might account for why so few white Americans know even one non-white person whom they’d consider among their closest friends or relatives?

- If you are white, do you know a “person of color” that you’d consider very close to you (close friend or relative)? If yes, in what ways is that relationship the same as similar relationships with white people? In what ways is it different?

- If you are a person of color (with neither parent white), do you know a white person that you’d consider very close to you (close friend or relative)? If yes, in what ways is that relationship the same as similar relationships with people of color who share your heritage? In what ways is it different?

- If you’re a person of color with at least one white parent (whether you are both parents’ biological child or you’re adopted), how do you see yourself in relation to your parent(s) who do(es) not share your racial identity?

- If you are of mixed race (parents are of different races) or you were adopted and your parents do not share your racial identity, do you identify yourself with one race over the other(s) or do you identify more with your birth race or parents’ race? Why? How much has race determined who your friends are?

- Given the issues people of color in general — and Black people in particular — face living in a majority-white country with a history of slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, redlining, etc., what additional concerns might they have if they also have Autism Spectrum traits (whether they know it or not)? How might that influence if/ how they’re diagnosed as well as treated? How much of that have you experienced or witnessed?

E 4: This Question Set addresses pets or therapy animals for the first time in this work. Desiree (Deedee) has Emma, a therapy dog, to reduce anxiety. Anxiety — nearly universal for those with Autism — is itself addressed by Question Sets in prior chapters: B-13 & C-6.

- Do you have pets at home? If more than one, do you have a favorite? Do pets respond well to you? Why do you think a pet may prefer one member of the household to another if that appears to be true?

- Do you or did you have a therapy animal yourself? If not, do you know someone who does? If you haven’t had one, do you wish you did? Are you jealous of someone else’s therapy animal?

- How is a therapy animal like a pet? How is it different? If you have a therapy animal — or if you don’t, but wish you did — what does, or would you imagine it would help you do?

- Have you experienced having a regular house pet (dog, cat, etc.) help you in some way, even if it’s not an official therapy animal?

- Is there an issue where you live that gets in the way of having the pet you’d want?

- Cheryl (Desiree’s mom) says Aspie Mouse is Bobby’s therapy animal. In what ways do you believe that is true? In what ways do you believe Aspie Mouse is not a therapy animal?

E 5: On page E3, Cheryl Jean makes the observation that while both Bobby and Desiree (Deedee) both have IEP’s (probably for Autism), Bobby has “no filter” for what he says, while Deedee hardly ever says a word. Autism is described as a condition of opposites, where different people tend to one extreme or another. For the following situations, which side do you fall on? Is it one extreme or the other, or for some characteristics, are you really in the middle? Ask someone who knows you well if they agree with you, especially for any where you believe you’re in the middle.

- I say whatever comes in my head (no filter) OR I hardly ever say much (don’t want any trouble)

- I’m always asking a lot of questions OR Even when I don’t understand, I don’t ask questions.

- I speak in a monotone, with little expression OR I’m overly dramatic, as if always on stage

- I prefer being alone or with those younger OR Some people intrigue me, so I almost stalk them

- I’m very picky when it comes to food OR I’ll eat just about anything

- Touching other people mostly annoys me OR I really crave physical touching (non-sexual)

- I’m really passionate about politics OR I usually avoid political discussions

- I love watching sports on TV or live OR I don’t watch sports on TV

- I love playing sports, at least one OR I don’t really like doing sports – or exercise

- I’m pretty messy; don’t pick up enough OR I’m a neat freak – everything in place

- I usually only take baths or showers when reminded OR I shower/ bathe daily at least

- I’m always moving: flapping, swaying, fidgeting OR I stay still so as not to stand out

E 6: (Following up from E 5) Bobby & Aspie Mouse talk/ ask questions a lot; Deedee says little.

- If you have Autism, do you say a lot and ask a lot of questions, or do you avoid saying much or asking questions even when you are unsure what’s going on, or are you in-between? If you don’t have Autism, what do you usually do when you have thoughts swirling around in your head? Or don’t you have that experience?

- If you talk a lot/ ask a lot of questions, are you aware that talking/ asking lowers your anxiety in the moment? Has “no filter” caused problems for you afterwards? What has it cost you? How have you been told you might lessen such problems/ costs? Has any of these “solutions” worked?

- If you tend to keep your mouth closed — even when you have plenty to say, or at least plenty of thoughts swirling around in your head — and don’t ask questions — even when you really aren’t sure what you’re supposed to do, or have serious concerns — what’s stopping you? Is it anxiety/ fear? What are you afraid what would happen if you spoke/ asked? Is it what happens to those from 6 b who say/ ask too much? What can/ do you do to overcome your silence when speaking/ asking is really called for?

E 7: It’s revealed that Deedee “bangs her head on a pillow” at night to help get to sleep; her mother notices that the more upset Deedee is, the more she bangs her head!

- Why do you think Desiree/ Deedee bangs her head on the pillow? Can you relate? What other “banging” of one’s head or another “risky” bodily behavior are you familiar with in another person you know? Do they have Autism? Why do you think they do it?

- Whether you’re Autistic or not, do you have some sensory or stimming habit, such as banging your head on a wall or pillow, or cutting yourself, or doing some other behavior that others get alarmed about?

- Do you have a sensory or stimming habit, such as flapping or spinning or using a fidget, per prior chapters, which aren’t physically harmful? Is/ are the response(s) by others to these other habits positive, neutral or negative?

- If you have a more physically “alarming” habit (per Q 7.2), what do you think is the reason you do it? Have other people told you they have a different opinion?

- Do you think the behavior (whatever it is) could be harmful? Would you like to find a less harmful way of getting out the energy or frustration or whatever it is that compels you to do it?

- If you don’t engage is such physically challenging behaviors, but know someone else who does, how does it change how you feel about that person? Are you afraid for that person? For yourself?

E 8: Aspie Mouse says he feels “lonely” in the house now that Bobby is gone and the new animal there (Emma) seems to just ignore him. (Variations of this question are in other chapters)

- Do you find it easy or difficult to make friends? If easy, why do you think that is? If difficult, is it due to: being quiet (introverted); having Autism; some other reason?

- Do you always wait for someone else to ask first to do something/ be a friend, etc., or do you find you do most of the asking? If you hesitate asking someone to play, do you fear being rejected?

- Do you have a lot of friends, just a few, just one good one, or none? Are you satisfied with the number you have? Are you satisfied with how truly honest you can be with at least one friend?

- What do you do with your friends? What would you like to do with friends that you don’t do? If you have friends but don’t do what you’d like to do, why is that?

- Aspie Mouse seems upset because Emma just doesn’t respond — rather than either going along (as all cats we’ve met so far have done, at least when awake, in chasing him) or rejecting him directly. Do you think AM sees the lack of response as being rejected? Do you think it’s the same if it happens to you? Are you able to ask “Why not?” and accept whatever answer is given as a gift?

- What kind of relationship do you think Bobby and Aspie Mouse have — playmates, companions, therapy animal and host, friends, something else? Would you classify the relationships you have with someone close, (especially if not romantic) if you do, as friends, companions, playmates, something else? What’s the difference for you?

E 9. When friendships get more complicated, as romance or other strong emotions occur.

- Do you find it easier to have a friend of the same gender/ orientation as yourself or is it harder? What makes it either easier or harder — or do you make sure to avoid making friends with someone you may find attractive as a possible partner? (Questions E.5/6,7,8continue on this theme)

- Aspie Mouse is not eager to consider #83 as a friend who could help reduce his loneliness. Why do you think that is? What could #83 offer to do — and/ or not do — that would likely make AM more willing to spend time with her?

- (Following from g) Do you think this difference in what AM and #83 want to do with each other would also apply to a situation where you and someone could either (or both) be a friend — to play with, have adventures with, hang around with, etc. — and/ or also a potential romantic partner? Might “moving too fast” on the romantic side have anything to do with losing (or never getting) that person as a friend?

- (Following from 8:) Do you see AM and #83 as doing a “role reversal?” That is, do you believe — as the author does — that it’s usually the male in a male-female pairing who tries getting physically closer “too soon” for the other? Or is that not your experience or expectation? If it’s usually the male who tries getting physically close too soon, is that more due to “nature” or society’s expectations?

E 10: Desiree and Bobby’s grandparents live very far away (have to fly), so they don’t see them often.

- Do you have one or more grandparent(s) who live close by or even at your home? Do you see them frequently? Do you feel close to this/ these grandparent(s)? Why or why not?

- Do you have one or more grandparent(s) who live far away? How often do you see them (if at all)? Do you feel close to this/ these grandparent(s) despite infrequent visits? Why or why not?

- Do you have one or more grandparent(s) that you’ve never met? Is that because s/he/ they are no longer living or for another reason? From what you’ve been told, do you wish you could have met them?

- Do you have other adult family members you feel close to in some way — aunt(s), uncle(s), cousin(s)? Is any a helpful resource other than your parents when you are dealing with feelings, problems or decisions in your life? If not, what kind of aunt/ uncle/ cousin do you wish you had?

E 11: Have you ever been in the position Desiree (Deedee) finds herself in at the end of the chapter — “losing” a friend (human or pet!) — to someone else?

- If yes, what were the circumstances that led to the human or pet friend choosing to spend more time with another person rather than you? How did that make you feel?

- If no, what does the thought of what happened to Deedee in this chapter — Emma ending up playing more with Aspie Mouse and spending less time with her — bring up for you?

- What do you think of Deedee’s attitude about “losing Emma” — that she didn’t need a therapy dog anymore? Would you be able to “let go” as easily as Deedee does (or at least so it seems)? What have you done or would you likely do in this situation — to try to win the friend back; to crawl into a shell; to seek another friend; to get “revenge”? What response(s) do you think would most help your own well-being (even if it’s not the one you did or would likely do)?

- What do you think about Cheryl Jean (Deedee’s mom) apparently being so happy that Deedee found her voice, that she’s now grateful — not angry — for what Aspie Mouse did? Cheryl also seems OK with Emma’s apparent gratitude for what Aspie Mouse did for (to?) Emma? What do you think you’d do if you were Deedee or Cheryl, and what happened in this chapter happened to you or a child of yours?

- Based on what Gloria Castelluzo says on the last page, how do you think she’d have reacted if what happened to Deedee had happened instead to Claire? Do you think Gloria’s attitude would be different — either more like Cheryl’s, or perhaps angry — if she were a neutral observer, rather than the “landlord” of Cheryl, Deedee and Emma’s house-sitting? After all, Gloria asked Cheryl to take care of Bobby’s “pet mouse” while the Castelluzos were away — so might she be feeling embarrassed hearing about Aspie Mouse causing “trouble”? What do you think you’d feel if you were Gloria? Bobby?