Notes meant to be read prior to reading Chapter Pre-A, Introducing Aspie Mouse (in the blog. When Vol. I of the Adventures of Aspie Mouse is formally published, it will be replaced by the Prologue now on the Front Matter page post)

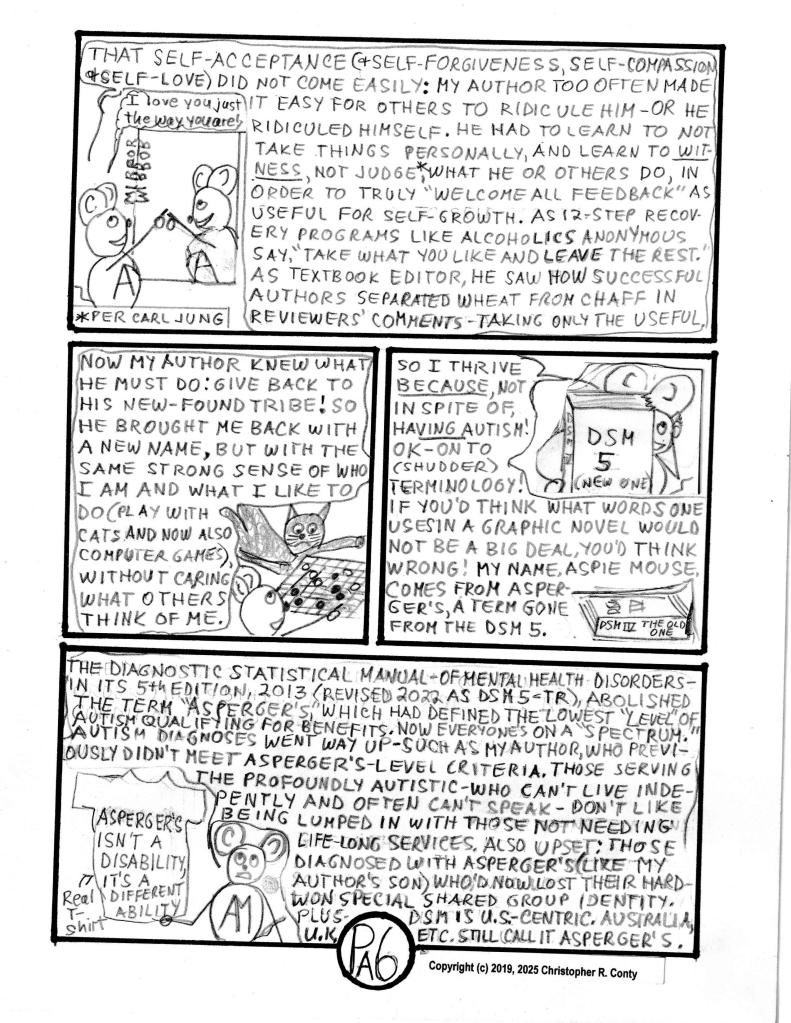

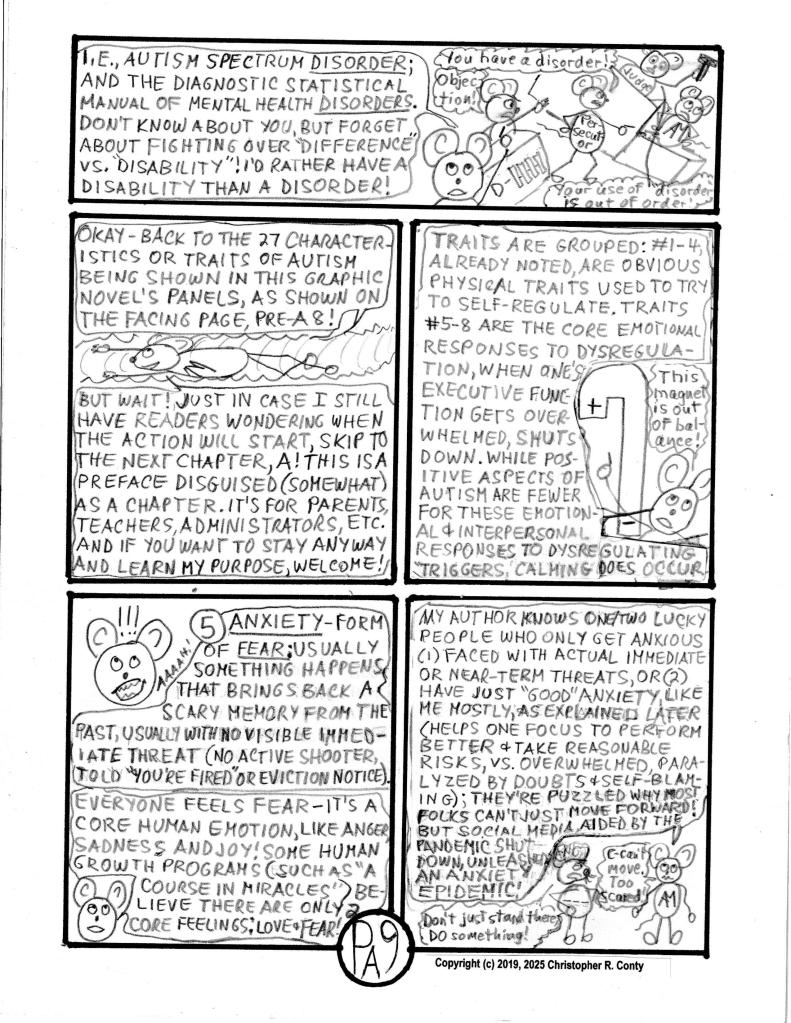

The following preface (masquerading as a chapter), Ch. Pre-A, “Introducing Aspie Mouse” in The Adventures of Aspie Mouse is written for teachers and parents. However tweens, teens and young adults, both on the Autism Spectrum and “Neurotypical,” are certainly permitted to read it. It’s a good intro to what mid-range Autism is all about — at, less severe or slightly more severe than what’s called Level I, formerly Asperger’s, and now more controversially “high functioning Autism.” However, many readers may find that this preface (and the notes for all chapters other than this one), gets in the way of just enjoying reading the chapters. Whichever type of reader you are, celebrate your good instincts for taking care of yourself!

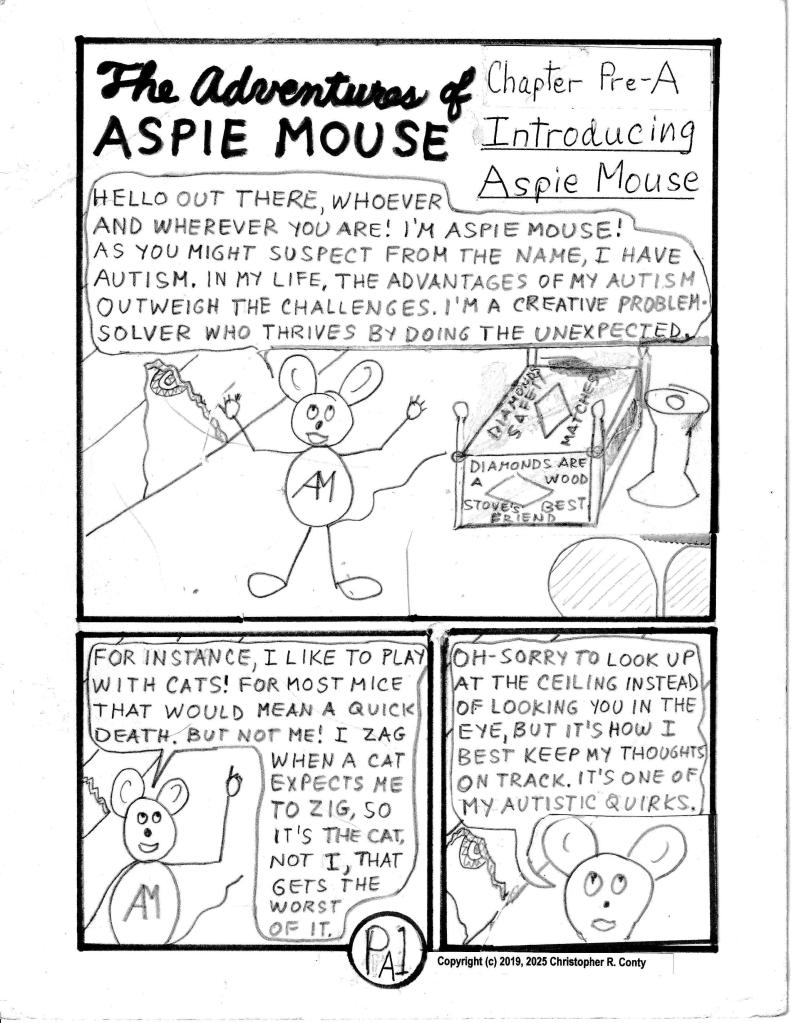

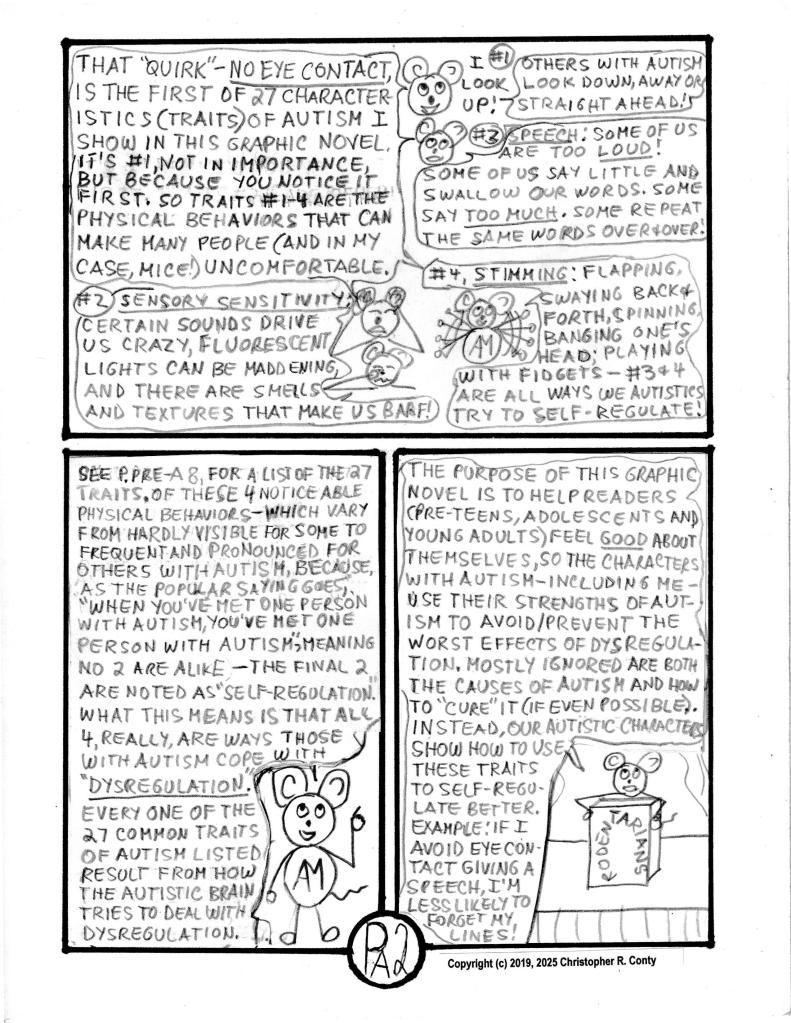

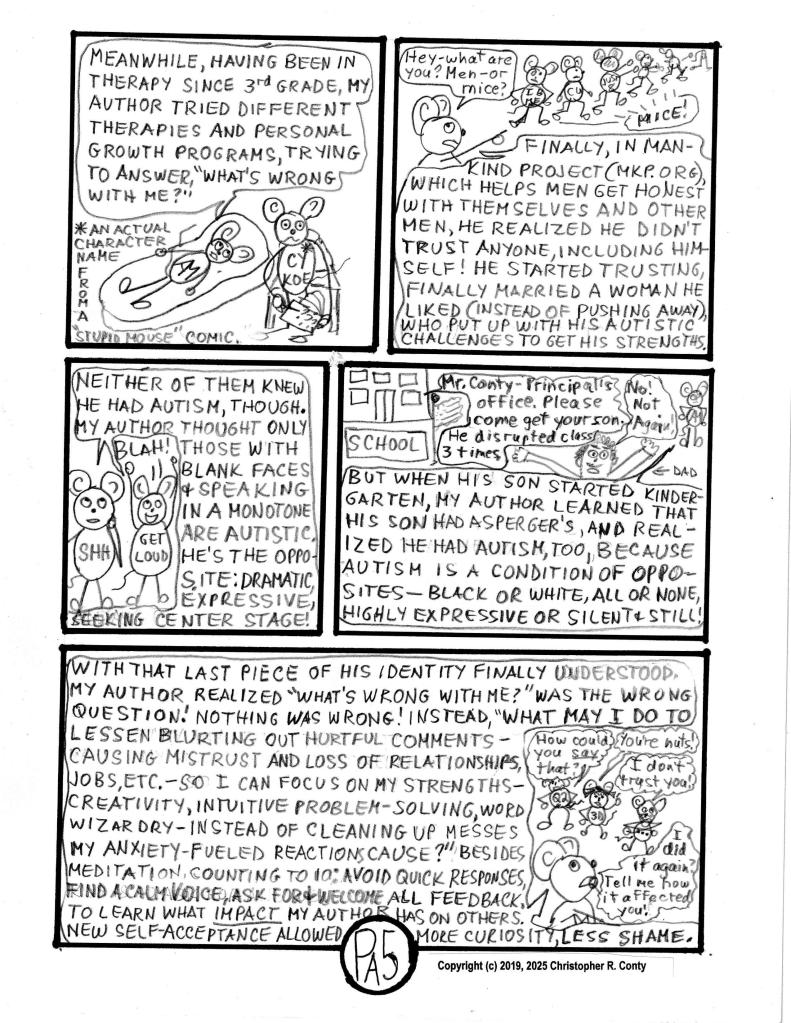

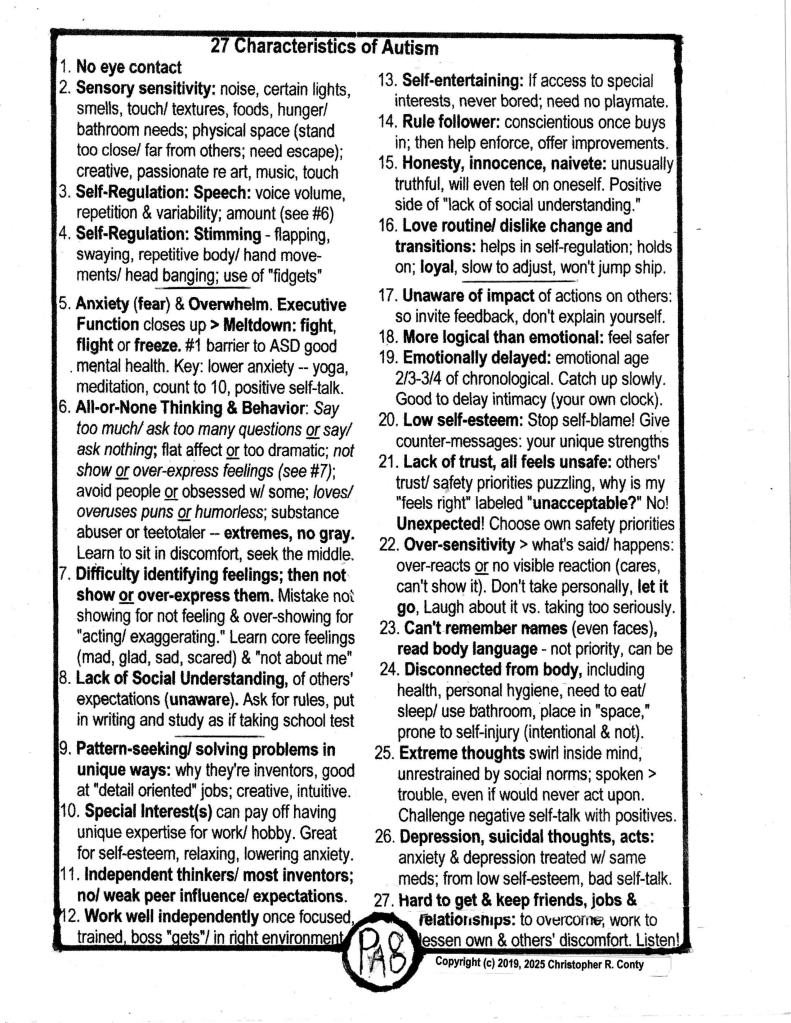

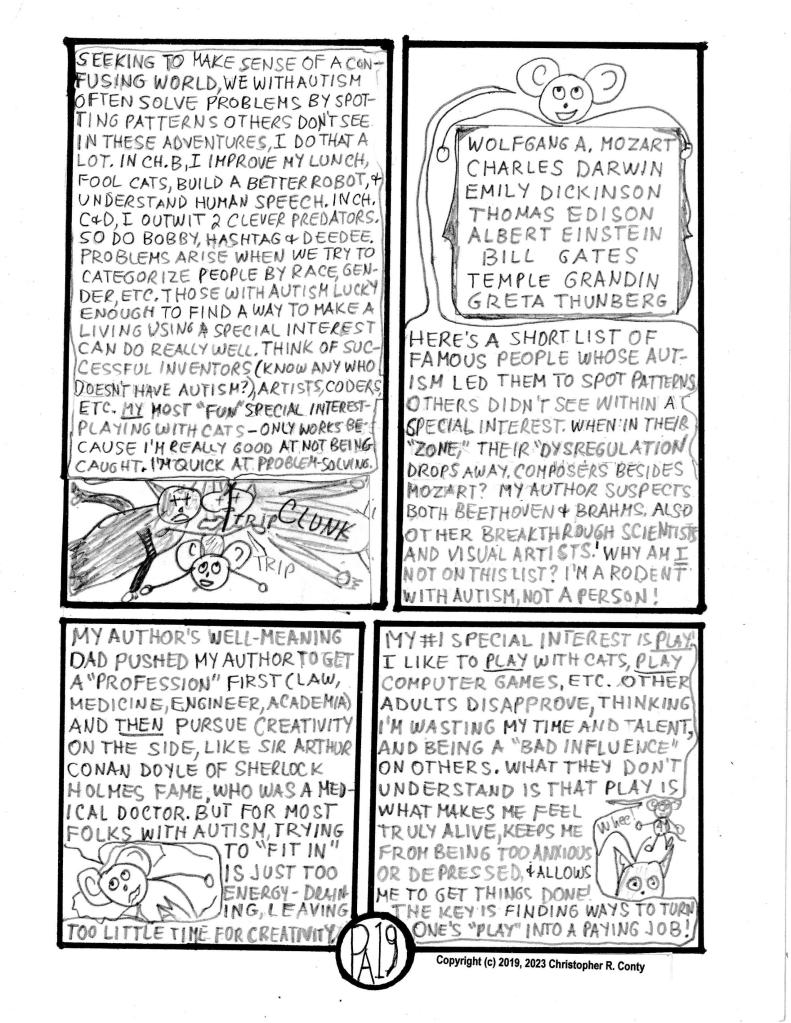

These Adventures center around an Autistic mouse named Aspie Mouse and his interactions with characters of various species — mostly other rodents, cats and humans — some of whom also have Autism. Others have other mental health challenges (especially the “villains” in Chapters C & D), while most of the rest are neurotypical. The primary focus of Ch. Pre-A is to discuss 27 identified Autism-related-traits, how they affect those who have Autism, and how — by focusing on each trait’s advantages (positives) — the Autistic characters — primarily Aspie Mouse — navigate through the world accepting themselves for who they are. Aspie Mouse in particular uses his Autistic advantages to not only survive, but thrive in a world built for Neurotypicals of all species. The 27 traits are listed on page Pre-A 8.

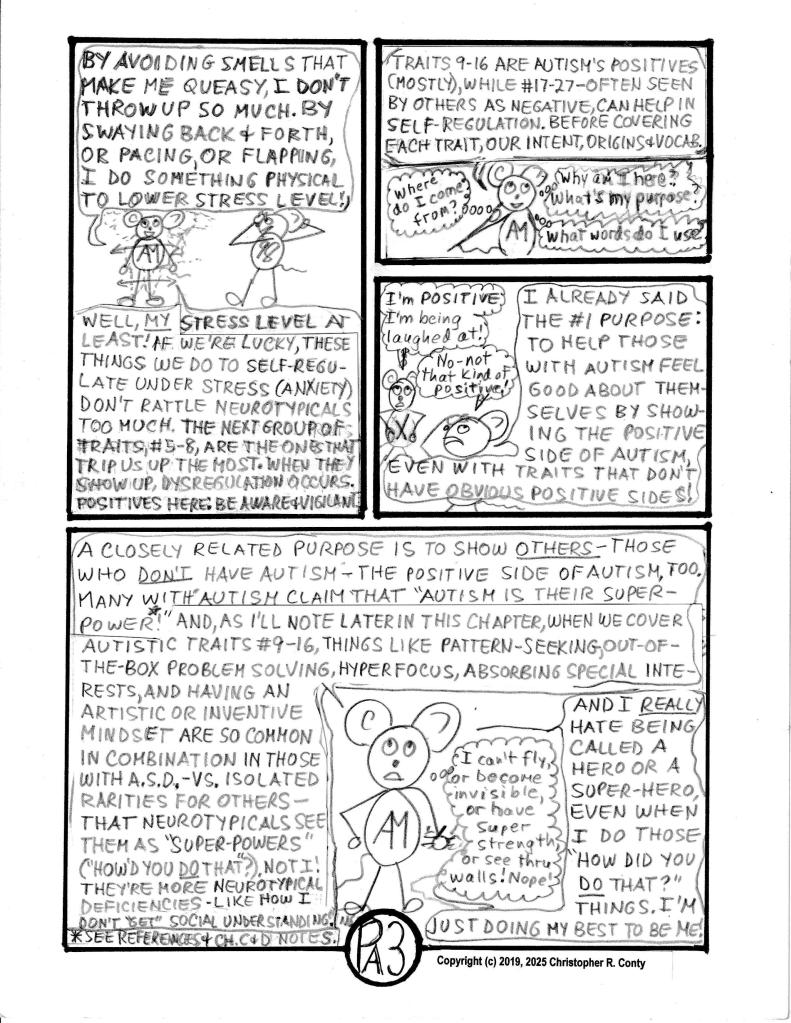

The purpose of these Adventures is to encourage readers to use the example Aspie Mouse and other Autistic characters set to: improve their own attitudes toward Autism; minimize dysregulation — such as fight, flight or freeze meltdowns — in response to unanticipated frustrations/ challenges; and develop useful work-arounds to reduce negative reactions from others who witness what they see as scary, unexpected and uncontrolled behaviors. Autism’s challenges are not minimized — if anything, they’re sometimes exaggerated. But these challenges don’t prevent Aspie Mouse and some other Autistic characters from thriving — not just surviving — because they’ve mostly figured out what works to: keep anxiety in the productive zone; keep dysregulation from causing disruption; develop a positive attitude toward themselves; and make good use of the useful life-affirming gifts Autism has given them.

Most folks read books that are fun, rather than those that are “good for them.” So Aspie Mouse’s adventures are designed to be entertaining, with lessons rarely spelled out in the panels of the lettered action chapters. It’s like making pasta from spinach: the “good for you” aspects are hidden. This is a graphic novel, not a handbook or resource guide to treating Autism! So, neither causes nor treatments/ remedies for Autistic behaviors get much attention. When they do, they’ll be in Ch. Pre-A, the notes that follow the action chapters (Ch’s. A-E in Volume I; F-J in Vol. II), or in the next paragraph.

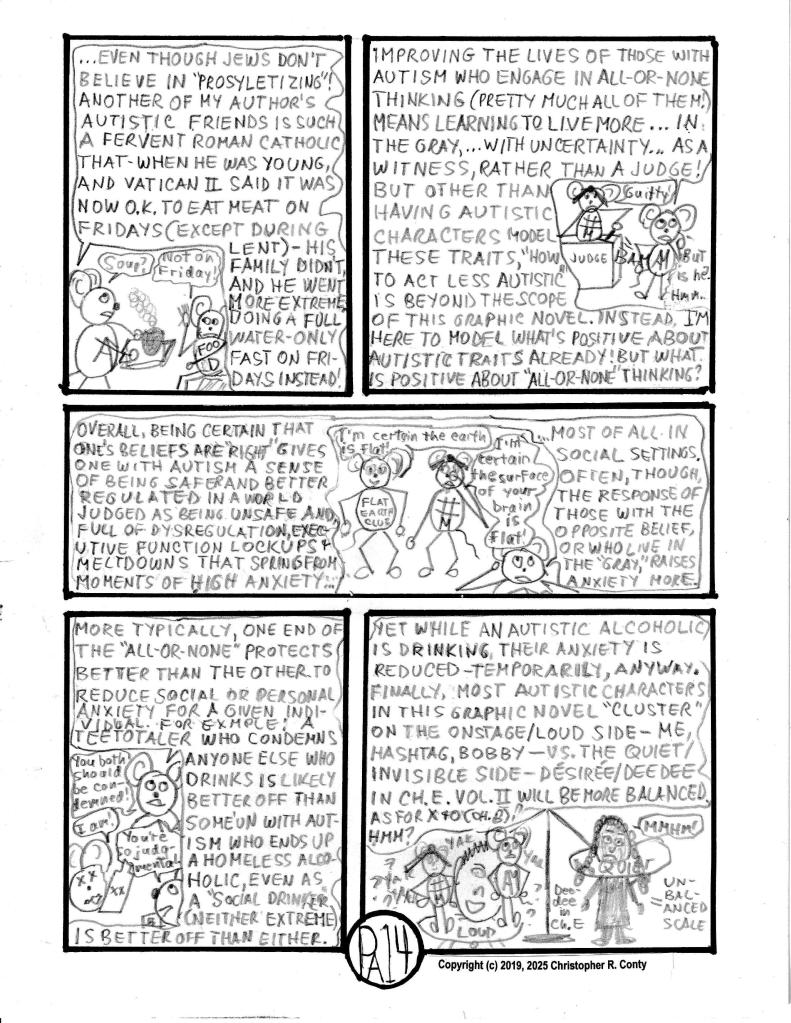

Even Autistic traits usually viewed as mostly negative — those numbered from 5-8 and 17-27 — are shown to have useful positive aspects, especially those behaviors which reduce anxiety and dysregulation, even if only temporarily. Even behaviors that have virtually no obvious positives — such as low self-esteem and depression/ self-harming thoughts and behaviors (self-cutting, suicide) — can be turned positive through education, therapy, coaching. One learns that these traits result from negative self-talk, based on what one’s heard all one’s life from a dominant culture that doesn’t understand Autism as a “different ability” vs. a “disability.” These negative voices can be overcome, or at least lessened, by “reframing” — changing one’s attitude toward these traits: “It’s not my fault I’ve felt this way”; “From now on I am committed to being self-accepting, self-forgiving, self-compassionate, self-loving”; “What other people think of me is none of my business” (credit to 12-step programs); “I can reframe what others say and what I think or dream to more positive interpretations.”

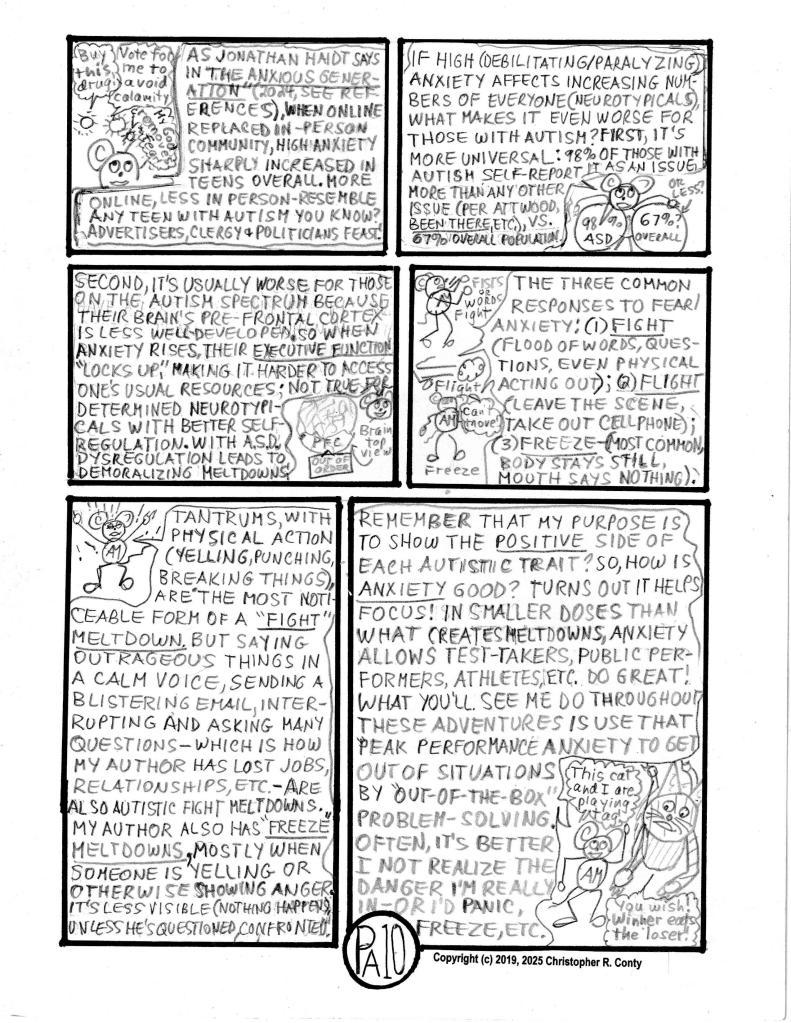

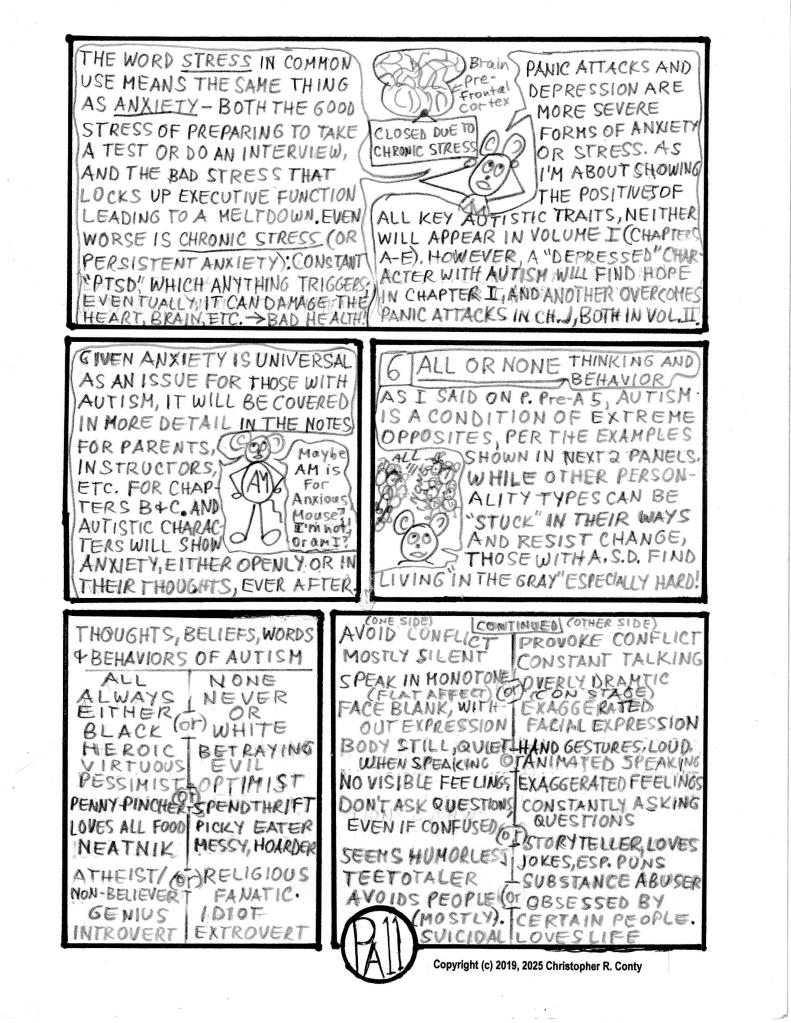

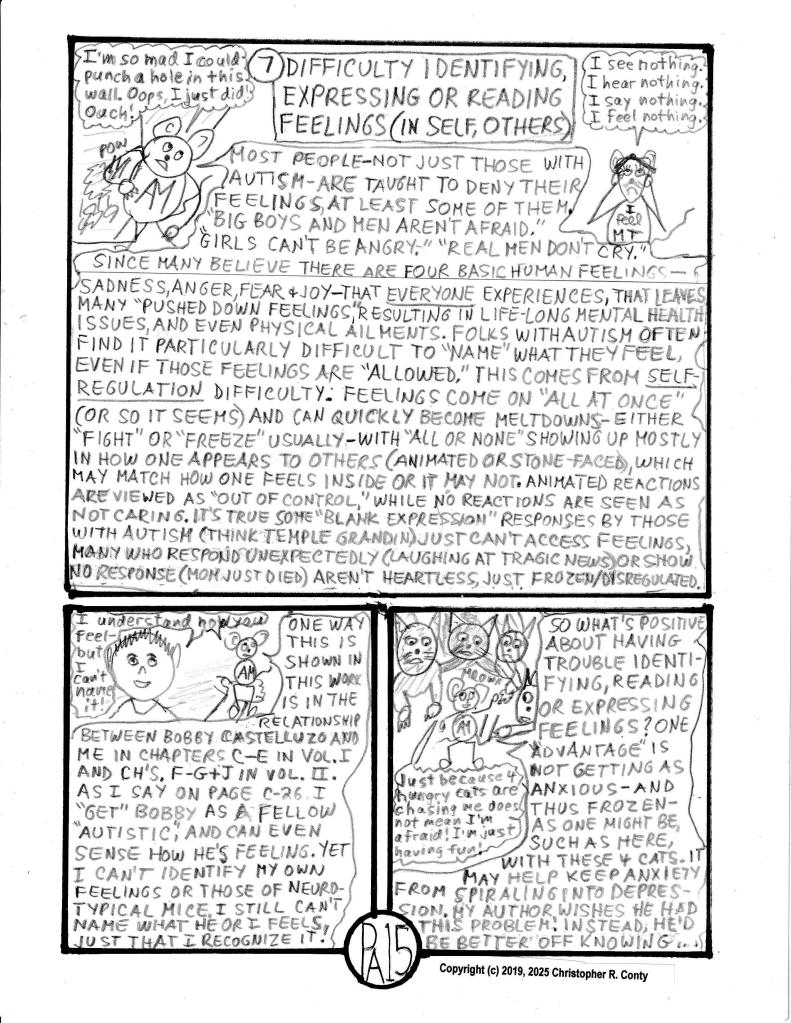

The #1 challenge for those with Autism is dysregulation: an inability to control one’s responses to situations after receiving the inputs from one’s brain (in terms of sensations, emotions and thoughts/ words/ actions of oneself, other people and the actions of other beings, machines, nature, etc.). The usual response to being (feeling?) dysregulated is anxiety (a persistent form of fear), which in A.S.D. is more likely to be triggering, paralyzing and frustrating, rather than motivating (the “good” form of anxiety). Once anxiety from dysregulation spikes high enough to shut down “executive function” (the pre-frontal cortex in the brain that controls complex social skills and reasoning, underdeveloped for those with Autism) when triggered — such that one’s usual access to resources close down — it leads to a “meltdown” (fight, flight, freeze) response. Successful Autistic characters in these adventures find ways to keep anxiety-provoking situations “exciting,” rather than overwhelming, thus taking advantage of the productive level of anxiety — that helps focus the mind and leads to outstanding results for actors, musicians, artists, inventors, speakers, etc. By avoiding having a meltdown, they may then use their creative powers to find unique ways of overcoming what most would consider overly stressful dilemmas. It’s indeed helpful that these characters — particularly Aspie Mouse — don’t care what others think! They’ve learned how to ignore or reinterpret panic signals from their brain to stave off dysregulation. They’re unconsciously “reframing” most of the time!

Non-Autistic readers should find some of these tools useful in their own lives. In the men’s work I do (mkp.org), 95% of the men come to us believing “I’m not worthy; I’m not good enough.” Only a small fraction of these men have Autism. Hopefully, non-Autistic readers — seeing characters with Autism doing positive things in the world despite so much push back against what the greater society says are unwanted, “unexpected” behaviors — will develop more empathy toward those in their own lives who have Autism. Both groups may better understand how these puzzling behaviors were developed by those with Autism as a defense against both crippling anxiety and social expectations that are difficult (sometimes impossible) for those with Autism to meet. Mutual understanding is the goal.

The most disabling characteristics those with Autism sometimes have — such as depression, suicidal thoughts, destructive obsessions, self-harm, etc. — don’t appear in Volume I (Ch’s. A-E). When they’re introduced in the last two chapters of Vol. II (Ch’s. I & J), they’re shown as manageable, and we see the characters supporting each other. Aspie Mouse, KK and Hashtag consciously re-direct the negative thoughts of themselves and others toward more positive responses in behavior.

Aspie Mouse (especially) often makes decisions without regard to social norms, creating amusing — even dangerous — situations, but gets out of them. He doesn’t realize the trouble he’s in, so he isn’t paralyzed or otherwise dysregulated. Instead, he sees patterns others don’t — zeroing in on what’s really going on from his perspective, paying careful attention (“hyper-focus”) — and draws on his ability to solve problems in unique ways. When others then call him a hero, he is genuinely confused: he was just trying to solve a problem, mostly unaware of the often greater positive impact his pattern-seeking/ problem-solving actions have on those around him. When his impact isn’t so positive — such as near the end of Ch. A (& H in Vol. II) — it’s made clear that he means well, yet he’s ignored signs as to how his desire to have fun is at others’ expense. It’s a key problem for those with Autism: the difference between intention (good for all) and impact (negative, so other(s) are upset, often with good reason).

Why does Aspie Mouse have a dangerous “special interest” playing with cats? It lightens things up, turns the tables on expectations (cats are supposed to go after mice, not the other way around!) and give a glimpse as to how different — and unexpected! — the thoughts and desires of those on the spectrum can be vs. the norm. It’s entertaining — fun! — to watch Aspie Mouse bamboozle and befuddle cats who don’t understand why they just can’t catch a mouse with no evident super-power — yet he keeps not getting caught, is apparently unafraid, and even invites them to chase him! For Aspie Mouse, playing with cats represents excitement. It’s what sky-diving, sports contests, amusement park rides do for many people, including those with Autism and ADHD: experience the positive excitement of focused attention and high adrenaline (good anxiety), without going into the paralyzing out-of-control lows of crippling anxiety and depression. It’s also what police, firefighters, the military and EMT’s do for a living!

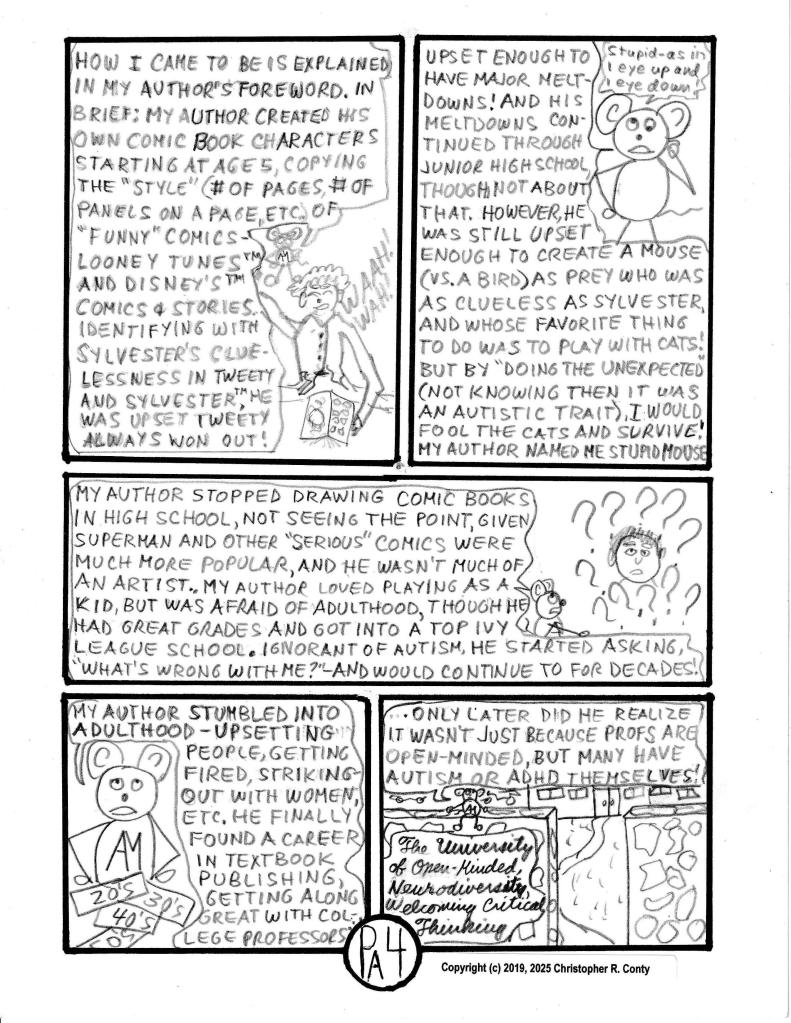

Why is Aspie Mouse male — and straight — during an era when non-white, female and LGBTQ heroes are so highly sought to bring balance to what’s been written for generations? Simple: he’s an avatar or alter ego for the author — who is also male, straight and white — Aspie Mouse is, however, gray in a world of gray, white and brown mice, with gray and white seeming to have most of the advantages. I’m writing what I know! However, other characters — Autistic and otherwise; human and animal — represent other perspectives on gender, sexuality, as well as having ethnic and racial identities. This isn’t tokenism, but very much reflects this author’s personal life experience with people from varied backgrounds — starting with two African-American brothers I met at age seven, to whom Volume I is dedicated, because of their influence on my cartooning (See Notes for Ch. E). I have a bias against using “safe” Northern European names for white human characters — like I used to see on TV — because I didn’t know people like that!

A note to librarians and parents, especially those in conservative religious communities and states: This is a graphic novel designed to be appropriate for pre-teens of all backgrounds, faiths and traditions. As in comics published in pre-1970’s America, none of the characters is “anatomically correct.” Also, there is really no discussion of sex, gender issues, etc. in Volume I. There are some “love interest” themes explored, but Aspie Mouse always takes the high moral ground. As for Volume II, not sure yet; if any, it’ll be kept light and matter-of-fact. My goal is to help as many young people with Autism as I can, however that needs to be, and avoid getting caught up in the “culture wars.” Just be aware that those with Autism are more prone than others to declare themselves Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual, Trans, Questioning, etc. and at any earlier age. It’s not that those with Autism are more likely to “feel” these other ways — they’re just less willing to conform to peer and family pressures about anything!

I have a bias against using “safe” Northern European names for white human characters — like I used to see on TV — because I didn’t know people like that growing up in the Bronx (Black people had the Anglo-Saxon last names)! In choosing which ethnic/ racial groups should be represented for my human characters, I’ve used my own personal experience with people from these backgrounds, and thought carefully as to what ethnicity/ nationality/ race might make the story richer for their presence in a particular chapter or situation. I’m sad that only 1/4 of my own ethnic background (1/2 Swedish; 1/4 Irish; 1/4 Italian) is represented through Chapter I in Volume II so far, and that many of my many friends of various ethnicities aren’t represented yet either. Not that many human characters!

A key purpose of this work is to improve self-esteem for those with Autism by showing them that their “non-social” (vs. anti-social!) thoughts are OK to have. However — and here social conservatives may agree with me — having these thoughts is very different from acting on them! Being told having these thoughts/ dreams are nearly as bad as acting on them is not at all helpful for helping someone with Autism have good self-esteem and be productive!

Apologies for delaying publication to 2025, after starting writing in earnest in 2019. Too many other obligations! Still, I had 10 chapters written (Pre-A to I) by 2022. Yet I realized I needed to make more changes — recently tying the 27 traits of Autism to chapter actions (without calling attention to them in the chapters), and adding “thought balloons” when a character’s thoughts are more revealing than what they’re saying out loud. Also I split the work into two volumes to avoid yet another year’s delay. I hope the results justify the delays!

Keep sending in your feedback — it’s all really helpful. I’ve learned to welcome all feedback!

Chris Conty, Author, Aug. 10, 2024 (slight update 2/22/2025); Need to completely replace the pages of Ch. Pre-A. As of 10/30/2025, 28 pages have been updated out of 34-36 projected. A partial replacement may still occur, but full replacement may occur instead.

Reblogged this on Aspie Mouse Blog.

LikeLike